Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Debating the A Priori by Paul Boghossian & Timothy Williamson

Teresa Britton debates with debates about reasoning.

There was a time when the a priori – it means knowledge that’s gained independent of experience of the world – was simpler. The metaphysics was lofty and so, following in kind, was the epistemology, that is, the theory of knowledge. For instance, Plato claimed that all things in our everyday world are imperfect copies of objects in the Realm of the Forms. This abstract perfect world could only be known by a kind of sacred epistemic ‘staring into the sun’, particularly when considering the Form of ‘the Good’. Here the a priori method of pure reasoning was the holy light of the intellect. It was separate and distinct from sense perception because it needed to be.

These days it is widely assumed that our powers to know philosophical, mathematical, logical, and all manner of purely reasonable abstract truths, are more human than divine. Skepticism that we can know anything independently of worldly experience emerges straightaway from skepticism about the nature of the abstractions we would need to access to do so (such as God, or the Forms). To take another example, postulating a non-Euclidean geometry immediately makes us wonder how many geometries there are to know a priori. Even two seems like a problem – not mainly for geometry itself, but for our knowledge of it.

A priori literally means ‘from before’, and it is sense experience that the a priori comes before. Immanuel Kant thought a certain type of a priori knowing provides the framework needed for any and all other knowledge. Certain categories of understanding must exist in our minds, he says, because without them no knowledge of the world would be possible at all. They are the preconditions for us to experience sensory representations of the physical world we inhabit, including logical relations and quantities.

From Kant to a fully informed naturalism, categories, judgements, methods are difficult to individuate, and eventually it all gives way to a seeming intractable epistemic holism, in which the interrelated justifications of our beliefs about the world are enmeshed with beliefs which circle back to have as their object the abstract scheme that holds that world of beliefs together. Furthermore, in the natural world of mechanisms that produce true belief in the human mind, the a priori, as with all knowledge, is found to be related to the social context of each thinker. Others can often point out errors in our reasoning better than we can ourselves. Yet our complex psychological pathway to a priori beliefs includes experts and colleagues whose own cognitive apparatus can share information to us only a posteriori – that is, through experience, primarily experience of whatever and however they choose to communicate to us. These are problems for the simple Platonic picture of a priori knowledge with which we began. (Moreover, isn’t staring into the sun itself a kind of perceptual knowledge?)

In their book Debating the A Priori (2020), Paul Boghossian and Timothy Williamson take all of this on and move the debate forward in illuminating ways. The book evolved from a series of papers which span over two decades, and which unfolded into a spirited back and forth between Boghossian and Williamson.

The title of Boghossian’s opening chapter, ‘Analyticity Reconsidered’, tells us where we are going. The two authors present an approach to the issue of a priori knowledge based upon language and meaning. An analytic a priori statement is one that’s true just in virtue of the meaning of the words involved; for instance, ‘All bachelors are unmarried’, or ‘2+2=4’. For analytic statements, knowing depends on understanding concepts, rather than on seeing what’s going on around us. But from this logical and linguistic approach we are well placed to analyze what it means to understand a statement, and then and only then, know the truth and necessity of that statement. Understanding propositional content in this way is a kind of quick glimpse into the truth which involves neither a big metaphysics nor some god-like quasi-perception like that of Plato’s theory of Forms.

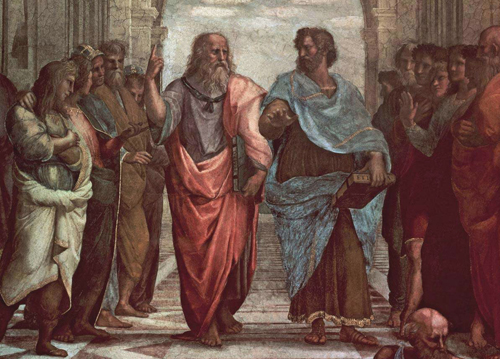

Plato & Aristotle debate a priori knowledge by Raphael

Throughout the book we stay in the world of language. You’ll encounter Carnap sentences, meta-semantics and Quine’s holism. Straight epistemology does also crop up too, as Boghossian analyzes good old intellectual intuition as a way to know synthetic statements. These are statements that reveal or define new ideas for us – such as Kant’s big example, “The shortest distance between two points is a straight line.”

From the back and forth of analysis and challenge emerges a framework of debate between two competing theories known as internalism and externalism. Boghossian, as an externalist and defender of the a priori, invokes a fusion of metaphysics and epistemology according to which the validity of an inference is the warrant for knowing it to be true. A good logical argument shows its own justification, we might say. Williamson takes the counter view: that while we can’t deny the existence both of methods of acquiring knowledge that don’t involve sense experience, and of those that do, this distinction isn’t what we thought it was. It’s hollow. That’s the position Williamson argues throughout. In the chapter ‘How Deep is the Distinction Between A Priori and A Posteriori Knowledge?’ he gives us a pragmatic and original route to his skeptical conclusions about the distinct nature of the a priori. He approaches the question of the category of a priori knowledge through a thought experiment that goes like this: How do you know that ‘The sun is shining’? You peek outside. But how do you know that ‘If the sun is shining then the sun is shining’? For this latter statement, you don’t need to look anywhere. You could have kept your eyes on the screen or page and still know that it’s true. Voila! There are definitely genuine instances of a priori knowledge – or in the jargon, the a priori has extension – but that’s only half of the story. When we turn to the intension of the term a priori – the intrinsic meaning of the concept – we find no underlying basis worthy of interest, he argues.

But whether skeptic (Williamson) or defender (Boghossian), it’s the analysis of the a priori as being independent of experience which matters. We are introduced to the difference between experience having on the one hand an evidential role and on the other an enabling role. We consider inner versus outer experience. One last stop on the journey is Williamson’s chapter ‘Knowing by Imagining’. Here he gives a thorough analysis of imagination as a source of the a priori. Imagination is philosophically overlooked compared to intellectual intuition, but it has the epistemic function of forecasting and discerning what’s possible.

However illuminating its exploration of language and meaning, the book does end up returning to a more familiar type of analysis of questions about knowledge. Are we externalists, for whom truth depends on facts external to the mind, ready to rally behind Boghossian’s ‘blind but blameless reasoning’? What do we think of reliabilism? This is the theory that a process for acquiring knowledge must be judged according to how reliably it produces true beliefs. Williamson sees what may be the heart of the matter: that the debate over the nature of a priori knowledge is in the end about our view of knowledge as a whole. If knowledge is not just true belief but is a state that one can lose given a change in context or challenges from other knowers, a priori knowledge will be so too. If so, then it will be vulnerable to challenges and complications from sense experience.

Their language-based approach works especially well in an analysis of skepticism about the a priori, I think; but I still want to look at a bigger picture to understand philosophical or even mathematical or logical methods of gaining a priori knowledge. Imaginings and inferences are both things we can do with our eyes closed, and hence are candidates for being a priori methods and generating known statements. But don’t we want to also study the whole of knowledge systems, not just the foundations? Knowing simple analytic statements, such as ‘bachelors are unmarried’ notwithstanding, conceptual analysis on a larger scale has to go beyond the formation of individual beliefs. Among other things, it involves theorizing, intensions, and extensions (echoes of Williamson’ own chapter), reflective equilibrium, and the evolution of concepts within a backdrop of competing concepts. How do we connect an a priori belief to the larger systems that emerge from these foundations? More work needs to be done, it seems.

In the end, the problems with the book are precisely those relating to the uneasy truce between modern epistemology and the throw-back idea of the light of the intellect shining onto a big metaphysical system. The authors get that. But without that clear big picture, we may always feel like we’re wandering in the shadows of science-based theories of knowledge – talking more about the impact of eye injuries on visual perception, say, than about the original and vaunted light of the intellect. Holism and contextualism, and the internalism-externalism debate, just get the last word here. What’s good about this excellent book is that it does manage to take us everywhere we need to go in this modern unwieldy epistemological landscape, and always headed in the right direction – into the concepts and content and logic of the propositions being known. The book is not a compendium, but because of its painstakingly careful analytics, it still reads like a complete and accurate map of the a priori in modern epistemology.

© Prof. Teresa Britton 2023

Teresa Britton is our Book Reviews Editor. Academically she specialises in epistemology and metaphysics. She is Professor of Philosophy at Eastern Illinois University.

• Debating the A Priori, by Paul Boghossian and Timothy Williamson, Oxford Univ Press, 2020, £33 hb, 288pp, ISBN: 0198851707