Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Nostalgia, Morality, & Mass Entertainment

Adam Kaiser finds a fine case of mass existential longing.

The box office has of late been dominated by remakes, sequels, comic book adaptations, live-action remakes of Disney films, and other spinoffs all aiming to help us relive those innocent thrills of our youth. If one word should be used to describe this trend of mass entertainment, nostalgia would seem the most appropriate. This nostalgia reverberates in different forms across media and subjects. In music, playlists are increasingly dominated by pop ‘throwbacks’, dating back a decade or more. Meanwhile, in the fine arts, abstract expressionism and postmodern art are under attack from both directions: one side calls for a return to the more traditional artistic ideals of the Western canon, while the other side has spawned a score of ‘-isms’ (‘Toyism’, ‘Stuckism’, ‘Remodernism’, etc), all attempting to reclaim a sincere sense of authenticity and meaning in their work. The Tate Modern in London recently ran an exhibition re-examining the work of early twentieth century German Magical Realists. Nostalgia has even infected politics, for example in a certain figure’s campaign slogan to ‘Make American great again’ (emphasis added). This apparent nostalgia is ubiquitous. But what is it, and why is it manifesting now?

Every generation is well acquainted with so-called ‘Golden Age’ thinking, but nostalgia appears to be a qualitatively different sentiment. In contrast to its ‘Golden Age’ counterpart, nostalgia does not long for any specific age gone past, but rather, for a lost internal state. Strangely, the current nostalgia [which isn’t as good as the old nostalgia Ed] is not overtly conservative, nor does it possess conservative strains of elitism. The objects of this nostalgia are not defined by their complexity or aesthetic quality. In fact, the opposite is closer to the truth. It peculiarly manifests itself in lowbrow culture – in things that would have been labeled ‘juvenile’ and smugly derided just a generation or so before. Deconstructionism, genre revisionism and irony are almost entirely absent from these new nostalgic works. The few features they all share are their simplicity, naivety (there’s an art movement called Toyism, after all), and most of all, their utter sincerity. To use, without prejudice, a term that carries an unfortunate and unintended negative connotation, these new nostalgic works are childish. Kids are not capable of wrestling with the full existential reality of existence, and equally so, the adult secular modern consumer retreats to their media to avoid confronting such questions.

Growing Backwards

To cut to the heart of this trend, I will start with a claim that is very broad, but is supported by many writers with existentialist leanings. This is that while modern Western culture has largely rejected conventional religion, historical metaphysical traditions, and many objective moral values, it is too cowardly to face head-on the absurdity and nihilism that inevitably follow in their absence. Those consequences are nearly impossible to even comprehend, much less accept, so we simply ignore them. We punt the ball along by turning back to comforts that portray the world as we would normally present it to children. In this world, right and wrong are clearly delineated and easily intuitive. Magic and the supernatural are taken as real, while serious issues of metaphysics and of life are avoided entirely. In this nostalgic world, people behave predictably and rationally in a near archetypal manner (have you ever seen a mentally ill hero or a truly sadistic villain in a children’s story?).

However, there is a paradox here. Traditional fairy tales, comic books almost always tried to introduce basic moral notions and religious themes to children. For example, in a 1999 interview, George Lucas claimed he created Star Wars to help kids develop a sense of God and spirituality (as throughout the entire series the heroes are defined by their spirituality as well as their belief in good and evil, while the villains practice occult manipulations and Nietzschean power politics). It is no coincidence that in the West the staunchest recent defenders of the value of fiction, fantasy, and fairy tales have come from the ranks of devout Christian apologists: J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and G.K. Chesterton. Their sentiment is wonderfully illustrated by Chesterton’s quote, “If you happen to read fairy tales, you will observe that one idea runs from one end of them to the other – the idea that peace and happiness can only exist on some condition. This idea, which is the core of ethics, is the core of the nursery-tales” (All Things Considered, 1908). One implication is that these works are only able to convey their intended value when viewed within the ethical paradigm from which they stem. So how does this nostalgia for orthodox stories and their moral lessons arise when we have mostly rejected the assumptions embedded within them? There has been no widespread religious revival.

In fact, the first impulse of most modern secular men or women who encountered these works was rejection. For decades, comic books and cartoons were considered unfit for adult entertainment; fantasy was the province of Dungeons and Dragons-playing misfits still living with their parents; and sci-fi was a secret hobby you didn’t tell your girlfriend about. Marxists and other secular intellectuals have always been on a spectrum somewhere between suspicious and hostile towards ‘bourgeoisie escapism’. Even now, there is still a degree of social uneasiness towards nostalgic works expressing old values. One can hear the complaints: ‘Disney princesses set a poor example for modern women’; ‘Marvel is too invested in the myth of the rugged individual’; ‘the Calormenes from Narnia play into orientalist stereotypes’. Such works are alienating to our supposedly enlightened secular sensibilities. So why are people still embracing them regardless?

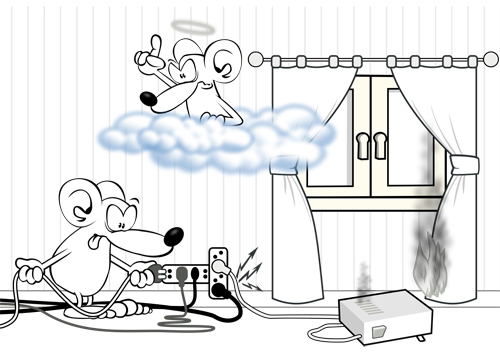

(If these aren’t the mice you’re thinking of, blame the lawyers of The Evil Corporation)

Mouse_heater_by_mimooh 2013 Creative Commons 3

Escaping the Cave of Reality

One critique of the existential tradition, made both by mainstream philosophers and by intellectual radicals such as Albert Camus, is that people cannot create their own moral values in the way that existentialists commend them to, and expect those values to have any objective or categorical importance. Rather these values become what Kant would have called mere hypothetical imperatives – nothing more than means to a subjective end of generating an experience of meaning.

Much ink has been spilled on the existential problems stemming from the Death of God, the decline of religiosity, and the crisis of meaning in an increasingly secular society. I won’t rehash those debates, except to agree with Søren Kierkegaard that it really is either-or: one cannot abandon all metaphysical anchoring and expect to find deep existential meaning in this life. And our choice of (how we see) reality will manifest in every aspect of our lives.

Given this, when the secular modern viewer comes into contact with works promoting traditional values, they might initially reject them; but in this rejection they are reminded of the absurdity that waits outside their safe confines. To all but the most stoic among us, the possibility of the absurd provokes more existential despair than we can tolerably bear, so its possibility inspires revolt within us. We revolt against our first reaction of alienation, and negate it. We suppress our first aesthetic reasoning, thereby committing a form of ‘philosophical suicide’.

This negation of our negative reaction gives birth to what we can call ‘ironic pleasure’. Throughout the post-modern era, when sincere enjoyment was out of favor, one could always ironically engage with ‘childish’ lowbrow media – so long as one did so with a wink and a nod, as if to say, “I don’t seriously enjoy this, I’m just pretending to, for now.” Of course, we always secretly really enjoy it. Still, this secret pleasure is always bracketed with the conscious knowledge that the work is ‘objectively bad’, in that it contradicts one’s self-proclaimed values or aesthetic taste – thus giving birth to the irony of the pleasure. This is why one simultaneously judges the person who sincerely enjoys bad or over-nostalgic work while also taking pleasure in it oneself. Still, since ironic pleasure is founded on a self-contradiction – to experience as good that which one knows is bad – it can never be ‘authentic’ or ‘sincere’. So, while irony may seem a possible resolution to the paradox of the popularity of unpopular values in popular culture, we soon realize that irony can never bring true satisfaction. It’s only a consolation prize awarded in the absence of sincere joy.

This understanding is what propels us to the emotional equilibrium of nostalgia. To flee the despair of nihilism, we long for the primordial innocence of the child that escapist works promise; but the modern secular person finds their traditional ideas false and alienating. Instead of turning back to the absurd, however, we overrule our objections and force ourselves to take a hollow, ironic pleasure in seeing depictions of old values. This is ultimately unsatisfying, so we are left in a state of nostalgia, a wishing for the state of innocence – as a result of longing for some comfort to insulate us against our overwhelming existential despair.

To return to mass entertainment – this longing manifests in the post-ironic culture taking root today. Audiences want to immerse themselves in a simpler world, where ethics are intuitive, people are rational, and meaning is self-evident. No longer is there the wink or nod to acknowledge the sardonic irony of the contradiction in wanting this, because people are beginning to understand the truth that unless we engage with these works on their own terms, we will never be able to obtain the comfort we long for from them.

However, there is still one step further to take. Not until we reject the need to create our own values, and return to a pre-Kantian metaphysical tradition of moral values, will we be free of the need to comfort ourselves with childish media.

This is not a call for ardent traditionalism, but an acknowledgement that we cannot consciously produce our own values without always being haunted by the knowledge their imperative is a fiction. When it comes to matters of the utmost importance, we can only learn, not create. This is not to say with certainty that there is any objective meaning to be found; but rather, that popular media choices reflect a desperate attempt to straddle an untenable middle ground. To those of us who long for the comfort promised by childish or nostalgic media, our comfort will never be enduring until we make the last movement of thought. The day we do so we will be free to appreciate these simple pleasures with full sincerity. On that day, as C.S. Lewis said, we will finally be old enough to start reading fairy tales again – unironically.

© Adam Kaiser 2023

Adam Kaiser is a PhD student at George Mason University studying philosophy, politics, and economics.