Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Irish Philosophy

Thomas Duddy & Irish Philosophy

Tim Madigan travels through time to seek the essential nature of Irish thought.

“There is of course such a thing as Irish thought, but it cannot be characterized in imperially nationalistic terms, or in any terms that presuppose privileged identities or privileged periods of social and cultural evolution.”

(Thomas Duddy, A History of Irish Thought, Routledge 2002, p.xii).

A few years back I had the pleasure of being the Faculty Director for a Study Abroad Program at the Centre for Irish Studies at the National University of Ireland, Galway (now known as the University of Galway). Part of my duties involved teaching a course to the twenty students who had accompanied me abroad from the US. Since I’m a Professor of Philosophy, I thought it would be appropriate to organize an Irish Philosophy course, but then realized that other than Bishop Berkeley, I knew nothing about any Irish philosophers, so I was in a quandary.

A month or so before the course was to begin I headed over to Galway to get things settled, and I visited the university bookstore. On one of the shelves was a book called A History of Irish Thought (2002). Intrigued by the title, I took it down and read on its back cover that it “rediscovers the liveliest and most contested issues in the Irish past, and brings that history of Irish thought up to date. It will be of great value to anyone interested in Irish culture and its intellectual history.” That was exactly what I needed: it cut the Gordian knot for me, as it were, in regards to finding a textbook for my course. I read that it was authored by Thomas Duddy, who I was glad to see “teaches in the Department of Philosophy at the National University of Ireland, Galway”. That added another nice component, to use a book by an NUIG instructor as the text. However, I soon learned that, sadly, Duddy had passed away in 2012, at the far too young age of 62, so I never had the chance to meet him. Still, his book allowed me to organize a course, not on Irish philosophy per se, but on Irish thought broadly speaking. Thanks to Duddy’s book I was able to explore with the students several lively Irish thinkers from medieval times to the present day. By bringing in figures from history and literature I could broaden the focus of the course, and explore the overall question, Is there such a thing as ‘Irish thought’? As our opening quote shows, Duddy most strenuously held that there is.

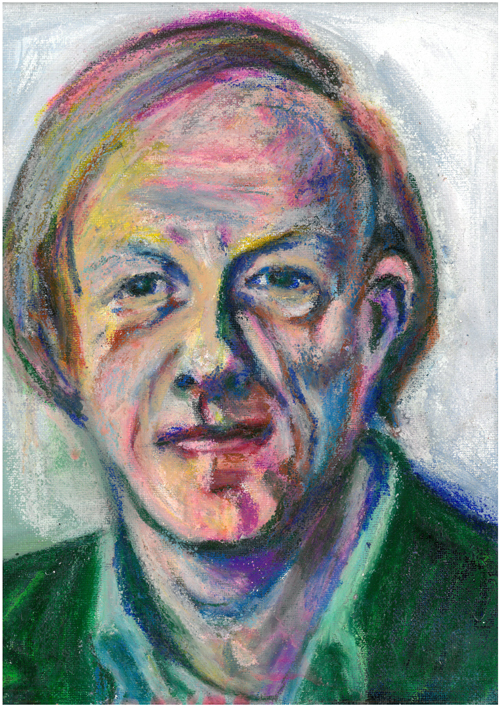

Thomas Duddy portrait by Gail Campbell

Out of the Mists of Time

A History of Irish Thought attempts to avoid narrowly nationalistic or sectarian conceptions of ‘Irishness’. In Duddy’s view, Irishness must instead be considered as inclusive, accommodating those who remained in Ireland as well as those exiled from it (either by decree or by choice), and most of all, allowing for multiple eccentricities and foreign influences. Duddy places special emphasis on the contemporary Irish philosopher William Desmond’s thesis that Irish thought is a ‘Being Between’ – a condition of thriving between different sets of extremities, such as between countries (for instance England and America), religion and science, knowledge and perplexity, and tradition and innovation. Irish thought, Duddy further holds, must be reflected upon in the context of being a colonized nation. Such societies, he argues, have a different story to tell than colonizing nations. “Instead of a history of shared vocabularies and shared frameworks continually exploited by like-minded individuals of talent and genius,” he writes, “there will be a history of conflicting vocabularies and shattered frameworks, sporadically and irregularly exploited by gifted individuals” (p.xii). Indeed, the book is filled with such gifted individuals grappling with historical contingencies, attempting to make sense of what is happening, and trying to forge a sense of identity. These include what he calls ‘accidental Irishmen’, as well as those born in Ireland – Catholics, Protestants, Pantheists, Atheists, and Pagans. It is indeed the fractured realities of Irishness – forged through invasions, oppressions, rebellions, uprisings, immigrations, and alliances – that has marked the nature of Irish thought. Duddy begins by discussing Irish monks of the Fifth Century, who, isolated from mainstream Europe, and especially from Rome, gave their own spin to Christian teachings. Slightly askew, genuinely unorthodox, if not vaguely heretical, they set the pattern for Irish thought going against the grain.

One point Duddy stresses throughout the book is how Irish thought does not make a hard and fast distinction between the prosaic and the poetic. Some of Ireland’s greatest thinkers have been novelists, poets, playwrights, painters, and performers. Duddy covers professional philosophers such as George Berkeley, Francis Hutcheson, Philip Pettit, and William Desmond; but also theologians like John Scotus Eriugena, James Ussher, and William King; scientists like Robert Boyle, William Molyneux, and John Tyndall; literary figures like Jonathan Swift, James Joyce, George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, and William Butler Yeats; historical and political figures such as Edmund Burke, Daniel O’Connell, and James Connolly; and some figures it’s harder to pin down, such as the philosopher/novelists Iris Murdoch and John Montague. Duddy also points out that many who took a literary rather than academic route nonetheless contribute to philosophical debates. Swift, for instance, in his Gulliver’s Travels (1726), skewers the popular rationalist philosophy of his time by creating the flying island of Laputa. The feet of the philosophers living there never touch the ground, and they have to be brought out of their constant cogitation by being hit with bladders by their servants. Duddy writes: “Swift’s description of the Academy is interesting not just for what it reveals of his attitude to scientific enquiry and invention but also for what it reveals of his attitude to the uses (and misuses) of reason in general” (p.161). There are rich insights amid the laughter provoked by the literary types, as any theatergoer who attends a performance of Irishman Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1952) can attest.

Yeats Contemplates

A key person throughout Duddy’s text is the poet William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), whose Irishness was ever-evolving and hard to specify. In many ways he is a pivotal figure in Duddy’s exploration of Irish thought. Yeats was an Anglo-Irish mystic, a reviver of pre-Christian legends, an enthusiast for (but not a participant in) the Gaelic Games and Gaelic language revivals, a poet, a playwright, a politician, a provocateur – but above all, an Irish thinker par excellence.

Duddy gives a sensitive examination of Yeats’ 1925 poem ‘Among School Children’, written when Yeats was a sixty year old Irish Senator, glad that the Republic of Ireland was finally independent from Great Britain, but worried about the growing Catholic emphasis on the government he served. The poem begins with him visiting a schoolroom in Waterford in his role as Senator. Yeats notes the young eyes staring at him, wondering why this old man is in their classroom. Suddenly he has visions of himself at their age, as well as visions of the woman he loved when she was a child. He reflects upon the views of such thinkers as Plato, Aristotle, and Pythagoras on the nature of the soul and its relationship with the body: material things come to an end, but images survive. Yeats next imagines himself as a baby in his mother’s arms, then has a vision of his young mother holding him now, a sixty-year-old smiling public man. Would she be proud, horrified, or saddened to see him as he is?:

What youthful mother, a shape upon her lap

[…]

Would think her son, did she but see that shape

With sixty or more winters on its head,

A compensation for the pang of his birth,

Or the uncertainty of his setting forth?

Duddy then writes, “Yearning and disappointment are expressed together in the plaintive, exclamatory language of the closing lines of the poem, as the poet turns to something that is alive, yet at the same time objective and invulnerable. The chestnut tree, though it is a living thing, is nonetheless so unified in its being that, blossoming and dancing as it does, one cannot ‘know the dancer from the dance’.”:

Labour is blossoming or dancing where

The body is not bruised to pleasure soul,

Nor beauty born out of its own despair,

Nor blear-eyed wisdom out of midnight oil.

O chestnut tree, great rooted blossomer,

Are you the leaf, the blossom or the bole?

O body swayed to music, O brightening glance,

How can we know the dancer from the dance?

In his poetic wisdom, Yeats brings forth some of the issues that philosophers have pondered for centuries. “Yeats”, Duddy comments, “is at his most ‘philosophical’ in his exploratory reflections on the notions of self and anti-self… For one thing, a public persona is something elicited from outside, something demanded from us by society, whereas the Yeatsian anti-self is forged from within by oneself, perhaps over against what society demands or expects” (pp.298-299). One can see how a ‘Being Between’ comes to exist within us all as we seek to forge our identities from our contrasting private and public selves.

It’s not surprising that Duddy gives such a sensitive reading of Yeats’ poem, since he was a noted poet himself. In fact, while I was in Galway, I attended the launch of his posthumously published book of poetry, The Years (2014). It was a very moving event, and in talking with those who knew Duddy as a professor of philosophy, and those who knew him as a poet, I noted how these two groups were mostly unconnected except through knowing him – another type of ‘Being Between’.

Duddy’s technical writings focused on the philosophy of mind and a neo-Cartesian defense of the self, as seen in his published dissertation Mind, Self and Interiority (Routledge, 1995). For poetry, in addition to The Years, Duddy also published The Hiding Place (2011), which was shortlisted for the Seamus Heaney Centre Poetry Prize, and the Aldeburgh First Collection Prize. As a young man he had to make an either/or choice: become a professional philosopher or dedicate himself to poetry. Exemplifying his own concept of Irish thought, he chose to do both.

My own take on Irish thought, à la Duddy, is that it is willing to accept paradox and ambiguity without feeling these must be solved or merged somehow in a Hegelian synthesis.

A Summation of History

A History of Irish Thought grapples with the myriad historical, cultural, economic, and social conditions faced for centuries by those living in Ireland, as well as by those who were exiles, either by force or by choice, yet who still remained connected to the Old Sod. It is amazing how many characters Duddy is able to juggle, and how clearly he explicates their works. He even brings us up to the present day.

As Duddy states in the Introduction to the companion work he edited, Dictionary of Irish Philosophers (Bloomsbury, 2004), today many Irish philosophy departments have (similar to most other Western institutions) Classicists, Continentalists, and Analysts in their midst; but there is also a fourth strand influencing contemporary Irish thought:

“Brash new traditions in the making outside of the Academy… In recent years there has emerged a new kind of Irish philosopher – one must resist the temptation to put philosopher in scare quotes here – who is producing work that might be perceived by the academics to be eccentric and ‘off the register’ but which is often more successful at finding an eager readership than the more methodical and discipline-based work of the academics. These non-institutionalized thinkers are playing an important role in making philosophy provocative and interesting to the general public, and many academics who are happy to write library editions for the university presses would do well to take a leaf or two from the kinds of books that these extra-mural thinkers produce.”

(Dictionary of Irish Philosophers, pp.xv-xvi)

One could say that Duddy, a professional philosopher with a gift for clarity and a love for the poetic, was the ideal person to make Irish thought accessible to the general public.

Although he passed away in 2012, Thomas Duddy continues to be an influence on Irish thought. What more could any teacher want than to be remembered as a positive influence? I heard from many who took courses with him who attested to the ways in which his gentle prodding continues to guide them. And the University’s philosophy department remembers him as well, with a Tom Duddy Seminar Room that preserves the books he used to write his own, and where many lively discussions occur.

Duddy also remains an influence on those who, like me, didn’t know him personally, but who take inspiration from his works. Catherine Barry, whose wonderful website on Irish philosophy was inspired by him, relates: “I never got to meet him, and having heard about him from others, I wish I had. I know him only through his writings, and I use his work every day. I agree with him that Irish people don’t know much about their intellectual history, and I agree that in the Irish self-image there is a tendency to downplay the intellectual side in favor of the artistic and emotional aspects. I would never have guessed that Daniel O’Connell had corresponded with Jeremy Bentham, or that an early philosophical refutation of the Atlantic slave trade was written by Francis Hutchinson from Down…”

Tom Duddy’s sympathetic approach to his topic shows that he was not only an able chronicler of Irish thought, but a major contributor to it. I hope that this article will encourage you to read A History of Irish Thought. In his own words from the Preface, “the time is surely ripe for the development of modes of reclamation and redefinition that are confident enough and generous enough to embrace Ireland’s neglected intellectual history.”

© Dr Timothy J. Madigan 2024

Tim Madigan is Professor and Chair of the Department of Philosophy at St John Fisher University. ‘Madigan’ is Irish for mastiff, meaning he ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog.