Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

M.M. Bakhtin (1895-1975)

Vladimir Makovtsev asks: M.M. Bakhtin, philosopher or philologist?

Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin (1895-1975) was a Russian philosopher, philologist, literary and cultural critic. He originated many new concepts, among which the most famous are ‘dialogism’, ‘carnival’, ‘chronotope’, and ‘the laughter of man’. But there is no consensus on whether he is a philosopher or a literary scholar, since he never wrote texts that dealt with ontology, epistemology, metaphysics, or other classical philosophical topics. During his lifetime, Bakhtin was known primarily as the author of two books, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics (1929) and The Works of François Rabelais and the Popular Culture of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (1965). For these books he was later nominated for the Lenin Prize, the highest state prize of the USSR. He did not win the prize but these two books eventually brought Bakhtin lifetime fame, both in the USSR and abroad. Although Bakhtin’s key works are devoted to the problems of fiction, the content of these works is much broader, which allows us to treat them as philosophical projects. In this respect, Bakhtin is rather like Nietzsche or Foucault, neither of whom were ‘classical’ philosophers, but who nevertheless had a major impact on philosophy.

So is Bakhtin a philosopher, or not? For me there is no doubt that he is, and to this I devoted my 2023 book Philosophy of M.M. Bakhtin: The Late Period. However, it’s not enough just to say that Bakhtin is a philosopher; one must point to the substance of his philosophy. What type of philosophy did he do?

I call it ‘literary philosophy’, to distinguish it from the philosophy of literature. In brief: the philosophy of literature is the application of philosophical methods to understand the nature of literature. Literary philosophy unfolds its thought exclusively in the space of the artistic text, using the medium of fiction to explore philosophical ideas. We will not find a single text of Bakhtin’s that in one way or another does not deal with literature or philology [philology is the study of the development of language, Ed]. But we resolutely cannot call his writings literary or philological only (indeed, philologists themselves often speak negatively of Bakhtin). This extra dimension eventually gave rise to a field called ‘Bakhtin studies’, or ‘Bakhtinology’. Really, though, the key theme of Bakhtin’s work is Dostoevsky. His philosophy is a hermeneutics of Dostoevsky’s work – a philosophical interpretation of its hidden meanings, signs and ideas - which is seen across his work and not just in his book on Dostoevsky. It might even be called ‘a philosophy on the way to Dostoevsky’.

Bakhtin is extremely singular even among Russian philosophers. He’s not a representative of religious philosophy, which is a popular strand of Russian philosophy. Nor is Bakhtin a Marxist, even though he lived most of his life in the Soviet Union, in which it was difficult for a researcher to remain politically neutral. Rather, Bakhtin is himself, and his fame is linked primarily to his key ideas, not to the fact that he represents some school of thought. But why is this so?

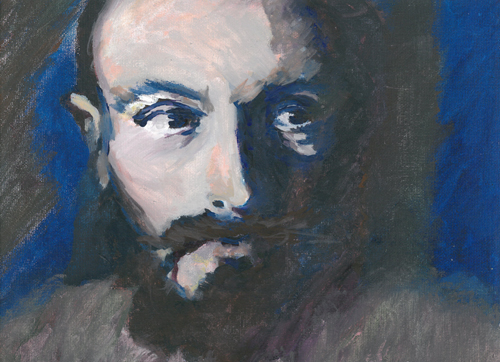

Bakhtin by Gail Campbell

Early Bakhtin

Mikhail Bakhtin was born in 1895 in Orel, in the Russian Empire, into, in his own words, a noble family. He belongs to the last generation of the Russian Empire, whose representatives received a classical education which would affect their whole outlook. In his intellectual spirit, then, Bakhtin belongs to that part of Russian culture which we call ‘the Silver Age’.

Bakhtin began his higher education in Odessa before moving to Petrograd University, where he graduated in 1918. The same summer Bakhtin moved to Nevel. There he became a schoolteacher, teaching art, literature, and religion. It was also there that the so-called ‘Bakhtin Circle’ formed, consisting of philosopher Valentin Voloshinov; and literary critic L.V. Pumpyansky; pianist Maria Yudina; poet, sculptor, and archaeologist B.M. Zubakin, and philosopher M.I. Kagan. In 1920 Bakhtin moved to Vitebsk and his circle of friends was enriched by literary scholar Pavel Medvedev and the musicologist Ivan Sollertinsky. According to some sources, it was here that Bakhtin began work on his book about Dostoevsky. Also during this time Bakhtin wrote Towards a Philosophy of the Act, The Author and the Hero in Aesthetic Activity, and The Subject of Morality and the Subject of Law, all of which became known only after his death.

It should be noted that the other members of Bakhtin’s circle were also major scholars, with overlapping interests. Some books published during this period under the names of Voloshinov and Medvedev are often attributed to Bakhtin himself, including Scholarly Salierism, Freudianism, Marxism and the Philosophy of Language, and others. These books are sometimes referred to as ‘Bakhtin in disguise’. It’s a controversial question in Bakhtin studies whether he wrote these books or not; but as far as I’m concerned, I am sure that these books do not belong to Bakhtin.

In 1921 he married Elena Aleksandrovna Okolovich, and three years later the couple moved to Leningrad (now St Petersburg), where the core of Bakhtin’s circle was retained.

In December 1928, Bakhtin was arrested by the OGPU secret police on charges of ‘counter-revolutionary activity’, including participation in the left-leaning cultural club Voskresenie (‘Resurrection’), which had now been declared an anti-Soviet organization. In 1929, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics was published. In July of the same year, on the basis of Article 58-2 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR, the Collegium of the OGPU passed a verdict to imprison Bakhtin in a gulag for five years. At the time, Bakhtin was in hospital due to aggravation from a chronic bone disease, multiple osteomyelitis. On the grounds of his poor health, thanks to the petition of friends, his sentence was commuted to exile to Kustanai, in Kazakhstan. The exile itself would last five years, but Bakhtin’s wanderings in obscurity would last until the early 1960s, the time of the Khrushchev Thaw. Bakhtin had to learn to keep a very low profile.

Exile

The exile in Kustanai officially ended in 1934; but Mikhail and Elena remained in the city for two more years, until Bakhtin was invited to teach literature at the Mordovian Pedagogical Institute in Saransk. However, in 1937 the situation inside the institute heated up, and denunciations and slander became widespread. This forced Bakhtin to suspend his teaching activity for some time. He wrote a request to be released from his position. In the order to remove Bakhtin from his post, the Director of the Institute wrote a note on June 3: “The teacher of General Literature Bakhtin M.M., for allowing in the teaching of General Literature bourgeois objectivism, despite a number of warnings and instructions, he still has not restructured, remove from work at the Institute.” The end of the 1930s in the USSR was a time of terrible repressions, so dismissal on such grounds might be called a favorable outcome. Nevertheless, with the arrival of a new director of the institute, this removal order was cancelled, and another issued, in which Bakhtin’s dismissal from his post was argued on the basis of his own wishes.

In 1937 Bakhtin and his wife returned to Kustanai and later settled in the Moscow region. In 1938, his multiple osteomyelitis worsened and his leg was amputated.

Since Bakhtin was formally repressed, he had no right to reside in Moscow itself, but could occasionally visit it on personal or academic business. He earned his living by teaching literature in various provincial schools. In 1945, Bakhtin returned to the Mordovian Pedagogical Institute, first as an assistant professor, and later as head of the Department of General Literature. He also, most importantly, finished his dissertation on the works of the Renaissance essayist François Rabelais, author of satires filled with grotesque and larger than life characters. He had worked on it during the terrible 1930s, had a typewritten version by 1940 and defended his PhD thesis Rabelais in the History of Realism in 1946. This thesis, which later formed the basis of his book on Rabelais, is a major work of literary criticism, including cultural studies, philosophical anthropology, and the history of ideas. It is also a powerful response to the horrors of repression that took place in those years in the USSR (which is why The Works of François Rabelais was not published until 1965). The main focuses of the thesis, and later the book, are ‘the laughter of man’ and the concept of carnival. Laughter, according to Bakhtin, is a powerful response to official culture; a response to the ‘truth’ that officialdom tries to cultivate. In fact, through the theoretical literary studies and cultural studies in this book, Bakhtin ridicules the official culture of the Stalinist era. Nevertheless, it would be naïve to think that Bakhtin was speaking in direct parables. Moreover, there is reason to believe that he did not set out to ridicule Soviet culture’s cult of ‘final truth’ and collectivism.

This work, like his book on Dostoevsky, is not strictly speaking ‘literary studies’, because it is much broader in scope. After his thesis defense, the examiners proposed that he be awarded the higher degree of ‘doctor of sciences’, not just the degree of ‘candidate’. The Higher Attestation Commission eventually rejected this recommendation, and Bakhtin’s actual awarding of the degree of Candidate of Sciences and issuing of a diploma only occured in 1952, when Bakhtin was fifty-seven years old.

Bakhtin was known and respected within Saransk where he taught. However, this fame did not extend beyond the university. But everything changed in the 1960s.

Late Period & Rediscovery

The early 1960s in the Soviet Union was the time of Khrushchev’s ‘thaw’, the time of the emergence of new names and the return of old ones; names in science, art and culture in general. It was a time of debunking Stalin’s cult of personality and of political rehabilitation.

The beginning of Bakhtin’s late period can be given to the day: November 12, 1960. On that day a group of Moscow philologists, Sergei Bocharov, Georgy Gachev, Vadim Kozhinov and Vladimir Turbin, wrote a collective letter to Bakhtin in Saransk. It is with this that Bakhtin returns to the academic space, and later to worldwide fame as one of the greatest Russian intellectuals. (Later, all these researchers, having become Bakhtin’s disciples, became major literary critics themselves.) In their collective letter, the authors expressed their admiration for Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, which, unlike its author, was not shrouded in the darkness of oblivion: this book was known, albeit to a narrow circle of specialists. Most importantly, in the letter the young scholars called on Bakhtin to (re)publish his works. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics was republished in a new edition in 1963, and The Work of François Rabelais and the Popular Culture of the Middle Ages and Renaissance in 1965. Special credit for the publication of these books goes to Bocharov and Kozhinov, to whom Bakhtin, who had no children, later bequeathed all copyrights to his writings. This gesture shows Bakhtin’s recognition of the role of those young scholars in popularizing his work.

However, there is a dispute as to who was most responsible for ‘discovering’ Bakhtin – who brought him out of obscurity, to become an iconic intellectual figure. In early 1961, that is, a few months after the letter from the Moscow philologists, Bakhtin received one from an Italian gentleman unknown to him. Vittorio Strada was a member of the Italian Communist Party and a seminal figure in the study of Russian culture and philosophy in Italy. Strada, putting together an Italian collection of Dostoevsky’s works, had come across Bakhtin’s book on him, and contacted the author. Strada suggested that Bakhtin contribute an introductory article to the proposed collection. Bakhtin agreed. This plan was not destined to come to fruition, as the publication of Dostoevsky’s collected works in Italy was delayed, but it had political consequences. This was because Strada had previously been one of those behind the publication in Italy of Boris Pasternak’s famous novel Doctor Zhivago (1957). The book had been refused publication in the Soviet Union due to its critical take on the Russian Revolution, but a manuscript had been smuggled to Italy. Its publication there, and the subsequent award of the Nobel Prize in Literature to Pasternak, had caused embarrassment within the Soviet Union resulting in the persecution of Pasternak, forcing him to refuse the Prize. No one wanted a repeat of such a scandal, so the prospect of poor, marginalised Bakhtin being prominently included in a prestigious project by Strada now created an urgency to publish Bakhtin in the Soviet Union first. In an interview, Strada acknowledges his role, noting that Bakhtin’s Dostoevsky book had previously offended some in the Soviet cultural establishment, but the very fact that a foreigner had now ‘rediscovered’ Bakhtin made them to want to promote it themselves, leading to it being republished. All this allows me to assert that the renewed interest in Bakhtin occurred simultaneously in Russia and in the West.

Julia Kristeva in 2005

Julia Kristeva © Guiness88 2005 Creative Commons 4

Another significant role in popularizing Bakhtin’s work belongs to French researchers, above all to the noted philosopher Julia Kristeva (b.1941). Kristeva was still a student in Bulgaria in a dissident circle of local ‘Westerners’ and ‘Slavophiles’ when her attention was drawn to Bakhtin’s books, recently published in Moscow. She and her friends saw Bakhtin as a synthesis of two important paths: an inner one, leading to freedom, and an outer one, linking together world culture into a single whole. According to Kristeva, Bakhtin inspired courage “in striving for the liberalization of the communist regime.” Later, after moving to a French university on a scholarship and having introduced the still untranslated Bakhtin to the French public with her 1967 article ‘Bakhtin, the Word, Dialogue, and the Novel’, Kristeva worked energetically to place him firmly in the European philosophical space, linking him to the Russian formalists, and, through them, to European structuralists and poststructuralists. She thus contributed to the creation of Bakhtin’s legend in French culture. She also introduced his works to Roland Barthes, who particularly appreciated Bakhtin’s ideas of dialogism and intertextuality. In 1967, Barthes asked in a letter to publish Bakhtin’s article ‘The Word in the Novel’. Bakhtin received this letter three years later. A draft of the reply has been preserved, in which Bakhtin regrets that the letter reached him with careless tardiness, too late to effectively respond to. Additionally, through Kristeva, Bakhtin’s name became known to the literary theorist Roman Jakobson, whose wife contributed to Bakhtin’s dissemination in the United States. As Kristeva notes, “Bakhtin was a real revolution both for adherents of formalism and for those who were beginning to take an interest in Western structuralism.” Her aim was, in her words, to “first point out his existence and place him in a French context. So it was necessary to interpret him for this French context, to make him readable for the French.”

Thus, three lines, interdependent and intertwined, equally claim to be the basis for Bakhtin’s return to the larger intellectual space. Each of them deserves its own attention.

Bakhtin’s Philosophy

So what makes Bakhtin a philosopher and why is his work so iconic? An original philosopher’s ideas are often characterized by a certain internal unity that permeates their entire body of work. What common thread do we find in Bakhtin’s oeuvre? Could it be dialogue, or carnival, or an interest in human problems?

All these are important, but we find the unity of his work unmistakably in his focus on literature. We must further say that the center of his interest in literature is Dostoevsky. Bakhtin was the first to look deeply at Dostoevsky’s metaphysics, linking it to the philosophical problems of man and the philosophical foundations of European culture. I have said that Bakhtin’s interest in Dostoevsky began in his early years. In the 1963 edition of Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, however, we encounter a synthesis of all of Bakhtin’s key ideas, developed throughout his life. These include ‘Dialogue’, which is the result of the development of the early concept of ‘the Deed’ and the philosophy of the word. In this edition of the book, Bakhtin also introduces one of his key ideas, the idea of carnival as a way of interpreting texts. Here he also explores the genesis of the novel as a genre, the origin of which he puts in Plato’s Socratic dialogues, and the apex as Dostoevsky’s ‘polyphonic’ novels. Thus, this edition is not so much a literary work as a philosophical and anthropological treatise, showing, among other things, the connection between Plato’s philosophy and Dostoevsky’s metaphysics. Therefore Bakhtin is also a historian of ideas, above all a historian of the novel. Indeed, we have before us an original philosophy that significantly influenced the intellectual community of the twentieth century, and which has not lost its relevance to this day.

Bakhtin wrote: “literature is an inseparable part of the integrity of culture; it cannot be studied outside the holistic context of culture. […] The literary process is an inseparable part of the cultural process.” Bakhtin closely identifies literature with culture – which implies that through the understanding of literature we understand culture, and thus understand humans themselves.

© Dr Vladimir Makovtsev 2024

Vladimir Makovtsev has a PhD in Philosophy from Lomonosov Moscow State University, and is author of the book Philosophy of M.M. Bakhtin: The Late Period (2023).

Bakhtin’s Concepts

Dialogism

Dialogue is the central concept in all of Bakhtin’s works. Bakhtin-style dialogue isn’t something taking place between isolated individuals, but occurs at the boundaries between individuals. Individuals themselves are not complete or self-sufficient but are always disordered and in a state of becoming. Bakhtin wrote: “To be means to be for another, and through the other for oneself.”

Polyphony

Bakhtin borrowed this term from music. When he talks of polyphony in literature he means a diversity of many simultaneous points of view and voices. Bakhtin argues polyphony is one of the main characteristics of Dostoevsky’s novels. To write in this way, the author needs to let his characters express themselves in a way authentic to themselves, without imposing his or her own authorial voice and opinions.

Carnival

Describes a phenomenon in which people meet in a sense of equality, united by some common purpose (as they might for example during a carnival). Such a situation sets aside all the usual social differences, and therefore subverts society’s power structures, either permanently or temporarily.

The Laughter of Man

“Laughter, according to Bakhtin, is a powerful response to official culture and to the truth that officialdom tries to cultivate.” A concept used by Bakhtin in his book on Rabelais.

Heteroglossia

The term comes from the Greek meaning ‘different tongues’, for heteroglossia is the many different varieties of speech within a single language. These can be regional dialects or forms of speech specific to different professions, classes or social groups. Bakhtin thinks these different speech forms represent different viewpoints each with their own meanings and values.

Chronotope

The term comes from the Greek meaning ‘time space’. It is about how time and space are represented within literature and speech.

Towards a Philosophy of the Act

After Bakhtin’s death, various unpublished manuscripts were found among his effects. Towards a Philosophy of the Act is the best known of those. Written in the early 1920s, but abandoned after the introduction and first chapter, it was finally published in 1984. It was an ambitious project to develop a new understanding of ethics. Bakhtin’s idea was to take Kant’s ethics as a basis but then de-centre it to recognise that humans are not finished and self-sufficient entities but are incomplete projects, developing in friction with one another (see Dialogism above). Our unfinished and evolving nature is pinned down and made concrete when we choose to act.

Rick Lewis