Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Tallis in Wonderland

Does the Cosmos Have a Purpose?

Raymond Tallis argues intently against universal intention.

The idea of a cosmic purpose is one which many of us are familiar with from religion. What happens in this world, so the story goes, is ultimately an expression of divine will. With the rise of science, the notion of a universe regulated by a deity has been displaced by one regulated by non-conscious physical laws. Being non-conscious, those laws are empty of purpose. Their regulative powers are also not external to the phenomena aligned with them. As the philosopher Helen Beebee wittily expressed it, physical laws are not “prior to and watching over matters of fact to make sure they don’t step out of line” (Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 61, 2000). Happenings are simply the patterns or habits of the unfolding natural world, unguided by a cosmic purpose. So that’s that, then.

Except it isn’t. For some thinkers the possibility of cosmic purpose has been revived by the very science that had seemed to have killed it. This resurrection is rooted in the discovery that the laws of physics must be fine-tuned to an unimaginable degree for there to be a universe that could generate and sustain life (or even the chemical complexity preceding life). Just how fine the tuning has to be is illustrated by the fact that the amount of dark energy in empty space – the so-called ‘cosmological constant’ or ‘vacuum energy’ – must be more than zero, but not greater than 10-122 units. This is necessary to ensure that the universe neither collapsed in on itself nor blew itself apart before clumping into habitable planets. The physicist Luke Barnes calculates that the odds of getting a universe fine-tuned for life are 1 in 10135.

To some this suggests that how things are in the universe is not a matter of chance. Things must have been rigged. Philip Goff develops this suggestion in his eye-popping Why? The Purpose of the Universe (2023). According to his ‘Value-Selection Hypothesis’, at least some of the fixed numbers in physics “are as they are because they allow for a universe containing things of significant value” (p.20). Those ‘things of significant value’ include, most importantly, human beings, and whatever is necessary to enable them to survive, and even flourish.

This, then, is the new case for Cosmic Purpose: that the constants of the universe are so unlikely they must have been laid down with an end in sight rather than just occurring randomly at the beginning of the universe. For some theistic thinkers, this licenses God’s return from the more than a century of exile into which He (or She) had been banished after the scientific revolution filtered through to culture. But not for Goff, who reminds us of the problem of evil. He argues that what he calls the ‘Cosmic Sin Intuition’ – the idea that it would be immoral for an all-powerful being to create a universe like ours that is so filled with suffering – rules out the existence of God, or at any rate a God who is both omnipotent and good. While this does not exclude an evil God, for whom the suffering of sentient creatures was the twisted purpose of His (or Her) creation, for Goff it is sufficient to rule out what he calls an ‘Omni-God’.

Pan’s Purposes

Goff mobilises his panpsychist views to support his argument in favour of a cosmic purpose. The universe, he tells us, is made of fundamental particles, each blessed with a rudimentary consciousness and proto-agency, such that they are “disposed from their own nature, to respond rationally to their experience.”

Goff made the case for panpsychism in Galileo’s Error: Foundations for a New Science of Consciousness (which I discussed in Philosophy Now 135). His central argument was that the one material object we know from within (so we have access to its intrinsic properties) is our brain, and that object is of course conscious. From this he believes it is legitimate to infer that consciousness is universally present in matter.

There are many difficulties with this argument. The most obvious is that of extrapolating from our brains to the universe at (very) large. There is also the so-called ‘subject-summing’ problem: how it is that the billions of micro-consciousnesses putatively associated with fundamental particles add up to the macro-consciousness of subjects like you and me?

These unresolved issues do not inhibit Goff from building on panpsychism and embracing its central thesis in Why?. With consciousness, he claims, comes purpose. The laws of nature have goals built into them, and those goals can be universal because consciousness is also universal: “fine-tuning and rational matter fit together like a key fits the lock it was made for”. Nobel-Prize-winning physicist Steven Weinberg’s notorious assertion that “the more we comprehend the universe, the more meaningless it seems” is here turned on its head. Courtesy of physics, the totality of things is seen to be radiant and that consciousness is imbued with consciousness

Applying the idea of purpose to the totality of things cries out for examination. Most obviously, there is a ‘purpose-summing’ problem analogous to the subject-summing problem. The most typical loci of purpose in the universe are individual conscious beings – which, even if we (momentarily) allow panpsychism, are still minute entities scattered rather scantily through a mostly empty universe, that in the case of human beings is 130,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times as wide as they are. Moreover, many features of purpose as manifested in biological creatures such as us, in whom those features are most elaborated, are incompatible with the idea of universality. Expressions of purpose in my life – and, I have no doubt, in yours – are localized, transient, and often conflicting. They relate to the real and imaginary needs of an individual who is situated in, makes sense of, and interacts with, a minute speck of reality. It is difficult to see how unified cosmic purpose can be so dispersed, and so granulated. What’s more, our personal purposes come and go: no individual purposes are sustained from the first howl to the final gasp. There are also conflicts, both within conscious subjects aware of their competing inner priorities, and between conscious subjects, whose endeavour to flourish may place them at odds with each other, such that my success is your failure, or vice versa. And if we look to construct an overall purpose from the sum of the different meanings that occupy our lives at different times, we are reminded that it is only when those lives are complete – and hence about to be cancelled – that they add up to a totality. The consoling thought that our individual lives can be judged as contributing to a bigger picture of human (and transhuman) progress towards a better world seems very vulnerable. Given the gathering clouds of irreversible climate change, and the reawakening threat of nuclear Armageddon, our unending progress seems far from guaranteed.

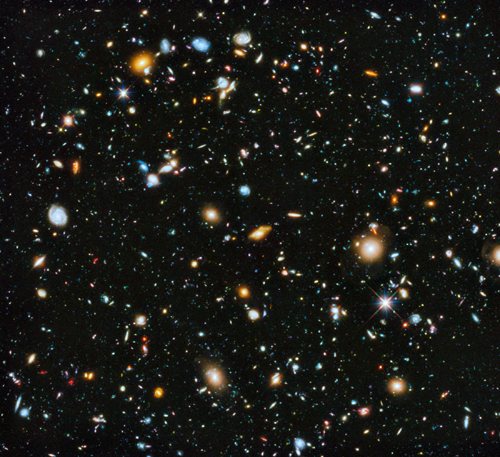

A small part of the universe: Hubble eXtreme Deep Field (HXDF) image released by NASA in 2012

Credit: Nasa; ESA; G. Illingworth, D. Magee, And P. Oesch, Univ Of California, Santa Cruz; R. Bouwens, Leiden Univ; & The Hudf09 Team

Cosmic Confusions

If we look beyond human life to life in general, conscious purpose appears singularly absent from the most authoritative account of the transition from single cell organisms to exotic megafauna like you and me, namely neo-Darwinism. The goals of individual organisms conflict with those of other organisms, either as competitors or simply living side-by-side, pursuing unrelated aims in parallel. It is hard to see prey and predators participating in a shared purpose. Furthermore, the differentiation of what-is into organisms and (their) environments seems to localize purposes in the former rather than the latter – which is at odds with the idea of the equitable distribution of purpose throughout the universe. As for the passage from atoms to minerals, and thence to the first stirrings of life, randomness and nonconscious mechanisms seem more evident than purpose. In short, the vision of a universe whose goal is expressed in the emergence of life and of rational organisms, appears counterfactual.

The point is this: the very idea of cosmic purpose uproots the notion of purpose from the places where the idea of purpose could have clear, or indeed any, meaning. Purposes as usually understood are anchored in lives, or parts of lives. They exist primarily insofar as they are entertained by conscious subjects or communities of such subjects, even though they may be ‘sedimented’ (to borrow Max Scheler’s term) in social institutions, or in the vast landscape of artefacts that humans create to support their lives. Purposes have intentional objects, however ill-defined. Nothing of this is preserved in the idea of a cosmic purpose – unless, that is, such a purpose is curated in the consciousness of the kind of deity that Goff rejects. This means that ‘purpose’ cannot be appropriated to refer to the totality of things without loss of meaning.

Even if the notion were accepted of a fine-tuned universe fulfilling a pre-ordained purpose in the transition from elementary particles to readers of Philosophy Now, the question of the execution of said purpose cannot be side-stepped. Goff seems aware of this and embraces pan-agentialism, according to which purpose is manifested through agency and “the roots of agency are present at the fundamental level of physical reality.” This, however, only exacerbates the problem of unifying localised, transient, conflicting individual purposes into an overall point for the universe. And there is, of course, the implausibility of ascribing to the fundamental constituents of the material world not only an awareness of themselves, and of (in some sense) what they are about, but of what’s happening to them so that they can purposefully manipulate their direction of travel. For Goff, however, there is no such problem: he envisages even elementary particles as being infused with ‘conscious inclinations’ by the pilot waves David Bohm proposed to make sense of quantum indeterminacy. As if this were not ludicrous enough, Goff embraces a ‘teleological cosmopsychism’, arguing that “If, during the first split-second the universe fine-tuned itself in order to allow for the emergence of life billions of years in the future, the universe must have in some sense been aware of this possibility, in order to act in such a way as to bring it about.” It seems unlikely that proto particles becoming an expanding universe could have had the bandwidth and foresight to envision that possibility.

Goff believes that the evidence for cosmic purpose “can give us hope that… the meaning our lives appear to have is not an illusion.” Unfortunately, any crumbs of comfort offered by a fine-tuned universe do not seem entirely convincing. After all, the vast majority of what exists is not only uninhabited in fact, but uninhabitable in principle, and thus void of purpose as usually understood. More damning still for Goff’s cosmic good cheer, recent advances in physics (as discussed in an authoritative paper by Fred Adams, ‘The Degree of Fine-Tuning in Our Universe – and Others’, Physics Reports, 2019), have suggested that “the universe is surprisingly resilient in its fundamental parameters” and “it is not fully optimized for the emergence of life.” So perhaps the cosmos didn’t have us in mind after all, and we are not unwitting contributors to the realization of its purpose. And even if we were, it would hardly be a source of comfort if we didn’t know what that purpose was.

© Prof. Raymond Tallis 2024

Raymond Tallis’s Prague 22: A Philosopher Takes a Tram Through a City will soon be published in conjunction with Philosophy Now.