Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

The Search for Meaning

Philosophers Exploring The Good Life

Jim Mepham quests with philosophers to discover what makes a life good.

I have attended a number of funerals recently and it has got me thinking. Imagine after you’ve died, your loved ones are sitting around, reminiscing about your life. What might they be saying about you? How will you be remembered? Did you have a good life? Well, how would they know? And what constitutes a good life, anyway?

The first thing to consider about what makes a life ‘good’, is whether the value of a life is determined by the liver of that life or by others. Suppose that your last thought before you died was that you had had an excellent life, but when your loved ones sit around and discuss you, they all decide that your life was awful. Is that possible? Could they be right about your life, and you be wrong? Or what if everyone else thinks your life was amazing, but you die miserable, feeling that your life was a total waste? Who would be right? And which of these two options would you prefer, anyway?

Ethics involve asking these deep questions about values. Other ethical questions include: Are you living the way you think you should? Are you working toward goals you actually care about? How important are these things to you? Right now, the choices you make about the way you spend your time are shaping the type of life you’ll live.

For the ancient Greek father of Western ethics, Socrates, “the unexamined life is not worth living.” For him, our life’s work (his idea of a good life) is to question one’s thinking rationally, and so to ‘know thyself’ through a relentless spirit of philosophical enquiry and dialogue with others.

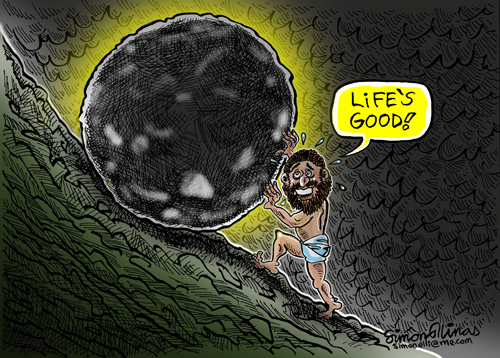

Writing in the twentieth century, the French existentialist Albert Camus recounted the ancient Greek myth of Sisyphus, who was condemned by Zeus to roll a boulder up a mountain everyday forever. Each time he reached the top, the boulder would roll back down, then Sisyphus would have to start all over again. This was the entirety of his existence. He couldn’t do anything else. It was up and down the hill, in a never-ending cycle. Strangely, Camus wrote, “We must imagine Sisyphus happy.” Why?

Image © Simon Ellinas 2024 Please visit caricatures.org.uk

As an absurdist, Camus thought that each of us is like Sisyphus, in that nothing that any of us does is inherently important, because life just doesn’t have any inherent meaning. We’re all just rolling boulders up our particular hills. We can, however, choose to give meaning to what we do. After all, for the existentialists, we decide what to value, so when we throw ourselves into a task, it becomes filled with meaning – a meaning we give it.

I find this account of Sisyphus depressing because, on the one hand, it’s saying that nothing you do matters, but on the other hand, it’s saying that anything that you do matters, provided you choose to imbue it with value: become a doctor and save lives; be a stay-at-home parent and look after children; create beautiful art works; find a career that gives you the space in your life to pursue a hobby you like; volunteer your time to promote a cause you care about; or just learn card tricks. In a sense it doesn’t matter what you do, what matters is that it’s meaningful for you. Basically, existentialists tell us that our lives and our meanings are in our own hands. So, if you’re unhappy, you should change your life. Do you agree with them?

In his book Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974), the American philosopher Robert Nozick asked us to imagine that scientists have developed the ultimate innovation in virtual reality, known as the Experience Machine. (We may not be too far away from this invention!) The Machine allows you to have any experience you like, for as long as you like – for an hour, a day, two years, even for the rest of your life, perhaps. Your body will rest comfortably, tended by nurses, and nourished through feeding tubes. Meanwhile, your mind will experience the best your imagination has to offer. You can achieve the fame and fortune you’ve always wanted, cure cancer, or heroically climb mountains – whatever you choose. However, Nozick sets the situation up so that you’ll forget you’re wired to the Machine, and the simulation is so complete that while you’re in it you’ll be convinced that these experiences are really happening. It will all feel as real as the experiences you’re having right now, and there will be no way to tell you’re in a simulation. Sounds great, doesn’t it?

Next Nozick gives you a choice of either an entire life inside the Machine or life outside it. He set the thought experiment up this way to ask whether pleasure really is the only thing we desire, since while in the Machine a person can have as much pleasure as they can imagine. But Nozick himself had no interest in entering the Machine for life, and he thought most of us wouldn’t either, just because the experiences it gives us don’t correspond with reality. So even though you might feel like you’re having meaningful relationships inside the Machine, in the actual world, you’re lying on a bed having simulated experiences of being with non-existent people. Nozick concluded that truth is also a value to us that is not superseded by pleasure.

If having an actual impact on the real world is important to you, that’s one thing the Experience Machine wouldn’t be able to give you. However, if you’re a hedonist – a person who believes ‘the good’ is equal to ‘the pleasurable’ – then simply having whatever pleasurable experiences you desire is what you most want. In that case, it might then be hard to see why you shouldn’t enter the Experience Machine. After all, it would let you experience things you could never have experienced otherwise.

What would you choose?

Aristotle, like his philosophical progenitor Socrates, had a clear idea of what a life well lived would be like. He wouldn’t agree with Camus that we must make our own meaning, nor that there are infinite ways to live a good life; and he wouldn’t endorse the use of the Experience Machine. Rather, he described the good life as a life of flourishing, in which a person is constantly striving for self-improvement – to be more virtuous, more wise, more thoughtful, and more self-aware. Aristotle believed in a human essence, which implies that there’s a proper way to be a human being, and live a human life, and that we’ll only flourish by finding that path. Aristotle defined humans as ‘rational animals’, so living a good human life means seeking to know your world, know yourself, and strive to govern yourself through reason. Generally, you should work to be the best, most virtuous version of yourself. But is this goal realistic? And can people who are suffering poverty, war, or torture then ever be said to have good lives?

For Aristotle, some ways of living are definitely better or worse than others. So if you want to be a good person living a good life, what you prefer has nothing to do with it. Choosing to just smoke pot all day, every day, or more generally, to simply indulge one’s pleasures, said Aristotle, is to live a bad life. This stands in stark contrast to the view we get from Camus, who said that we are all the determiners of our own values, and hence of the value of our own lives. So we have two contrasting views of ‘the good life’ here: one from a philosopher from ancient Greece, and one from twentieth century France. Which do you think is closer to the truth?

There is indeed a rich set of ethical ideas and disagreements about the good life, from many different philosophers throughout history. Other philosophers, from the Stoics and Epicurus onwards, can also illuminate our ideas on meaning, happiness, our obligations to others, our relationships, goals, love, and dealing with adversity and mortality. Existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Søren Kierkegaard, or Simone de Beauvoir will develop our understanding of subjectivity, freedom, and authenticity. And there are, of course, many modern thinkers who can expand, question, or illuminate our thinking here. ‘What is the good life?’ is, after all, one of the oldest philosophical questions. But is it a question about a moral life, a life of pleasure, a question of meaning, or is it about self-development and self-actualisation?

One of the values of philosophy is that it encourages us to think for ourselves, including about the nature of a good life. For Simon Blackburn, in his book Think (2001), philosophical awakening “enables us to step back, to see our perspective on a situation as perhaps distorted or blind, at the very least to see if there is argument for preferring our ways, or whether it is just subjective.” And for Bertrand Russell in The Problems of Philosophy (1912), there may be no definite philosophical answer to the question of whether, at the end of one’s life, one can say one has led a good life. Instead, “philosophy is to be studied not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation.” So doing philosophy may well be part of a good life. Do you agree?

© Jim Mepham 2024

Jim Mepham is a retired headteacher in Bristol who runs a number of philosophy groups, including for the University of the Third Age and Bristol Pub Philosophy. He also runs adult education workshops on Philosophy for Everyday Life.