Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Good Will Hunting

Tamás Szabados gives it an existential analysis.

The heart of the movie Good Will Hunting (1997) is an encounter between Will (Matt Damon), a twenty-year-old working class prodigy, and an apparently burnt-out middle-aged therapist, Sean (Robin Williams). This is in fact a story of a Buberian I-Thou relationship which deeply touches, upsets and inspires both men to the extent that they both end up leaving behind the comfort of their old habits, move out of their homes, and leave town. Martin Buber (1878-1965) was an existentialist philosopher whose thinking focused on the nature of human encounters, and this is a movie about what it takes from a Buberian perspective to be liberated from binding fears and take the dreadful first step that leads towards deeper awareness, more freedom, and a higher level of responsibility.

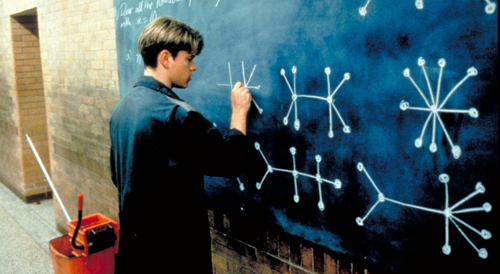

The opening shots show Will in a shabby, bare house on the outskirts of Boston, sitting on a chair speed-reading a book in the midst of other carelessly scattered books. Will is a janitor at Harvard University. We soon come to understand that the average working class lifestyle Will leads is in stark contrast with the brilliant intellect he possesses: in a break from mopping the floor, he sketches the solution to an extremely difficult mathematical problem left on a university chalkboard. This prompts Nobel Prize-winning professor Gerry Lambeau (Stellan Skarsgård) to seek him out. Lambeau finds Will being held for assaulting a cop. Thanks to the mathematician’s intervention, Will can avoid a jail sentence, but only if he agrees to regularly see a therapist. After several failed attempts with various therapists, Will finally accepts the authority of Sean, a childhood friend of Lambeau. Sean, who is originally from the same neighbourhood and social background as Will, stands up to the boy’s arrogant attempts to disqualify him, and eventually tames him into cooperation.

The encounter between Will and Sean is passionate and disturbing for both parties. Will makes Sean lose his temper at the first meeting by insulting his late wife; in return, Sean touches Will’s sore spot during the second session when he points out that behind the impressive intelligence and accompanying arrogance there hides an inexperienced, timid boy. But his relationship with Sean enables Will to face his fears and find the inner resources to move on, leave his safe environment, make use of his impressive genius, and take the courage to go after the girl. Following a long period of bereavement after his wife’s death from cancer, Sean also decides to leave town, and he sets out on a journey to India.

Janitor or Professor? Do the math

Good Will Hunting stills © Miramax Films 1997

An I-Thou Encounter

It is difficult to assess the eight-session therapeutic intervention presented in the movie from a professional point of view. Sean breaches a couple of ethical rules that could get him into serious trouble were he not in a Hollywood movie: he physically assaults his patient in the first session, and he regularly discloses information on the progress of the therapy to Lambeau. His therapy is highly unorthodox in other ways too. He holds the second session in a park; he ends the fifth session early and angrily sends away his patient because he is frustrated by his ‘bullshitting’ (this would be highly unusual even if he were a Lacanian); he also talks freely and abundantly about his own private life and suffering. One wonders if these sessions should be viewed as serendipity rather than therapy – an encounter in a special situation between two men with similar roots. Could it also be seen as Sean’s swan song? Will is quite possibly his last case ever – so intuitively feeling the looming life change and existential challenge that this encounter poses, he breaks all the rules. As a master of the art of therapy, he plays his last game free-style, sometimes even recklessly and dangerously. The treatment takes on the character of true horizontality, and gains an existential quality for both parties.

Although it is not entirely clear which school Sean follows, we can safely say that this therapy bears many marks of an existentialist-humanistic treatment. Indeed, the encounter between the two men serves as a beautiful illustration of the underlying premises of the existentialist approach, and especially of what Buber calls an ‘I-Thou’ relationship. So although I just characterised the therapist’s physical assault on the client as a breach of professional ethics, from a Buberian perspective we can reexamine it as a sign of deepest respect: by losing his presence, the therapist exposes himself to the patient and becomes extremely vulnerable. He is not only trying to teach Will that there are certain limits, he’s also taking a risk. The boy could easily have used the fact of being attacked by the therapist against him: instead he seems to feel that he is being taken seriously by someone.

In Existential Psychotherapy (1980), Irvin Yalom presents the difference between Buber’s ‘I-It’ and ‘I-Thou’ ways of relating:

“The ‘I’ is profoundly influenced by the relationship with the ‘Thou’. With each ‘Thou’, and with each moment of relationship, the ‘I’ is created anew. When relating to ‘It’ (whether to a thing or to a person made into a thing) one holds back something of oneself: one inspects it from many possible perspectives; one categorizes it, analyzes it, judges it, and decides upon its position in the grand scheme of things. But when one relates to a ‘Thou’, one's whole being is involved; nothing can be withheld” (p.365).

Lambeau’s relationship to Will would be an example of an I-It relationship. He sees Will as a member of an exceptional category: as ‘a prodigy’, as ‘the new Einstein’, as a huge potential that needs to be groomed so that he can contribute to the progress of humanity; but he doesn’t see him as ‘Thou’: he may act as a benefactor and a mentor, but he never actually ‘meets’ Will. By contrast, Sean is touched by Will from the first moment. He takes him seriously as a person and his ‘whole being is involved’ in the encounter. He ‘withholds nothing’, not even his anger and frustration. Sean is always authentic, transparent, and self-revealing in his relationship with Will. Equally, he resists all temptation to diagnose him. Even when he talks about Will’s past traumas, he uses common words instead of psychoanalytical categories. Over the sessions Sean creates an alliance with Will’s innermost being – the part of him that had secretly desired to be discovered. As Sean points out in a memorable conversation during the fifth session, no matter how hard Will is trying to make everybody believe he’s satisfied with his life, it’s actually Will himself who took the first step towards something new. As Sean says, “You could be a janitor anywhere. Why did you work at the most prestigious technical college in the whole fucking world?” There is someone within him that’s looking for achieving more of his potential.

It’s during the same session that Sean gets frustrated with Will’s evasive replies and asks him to leave if he continues ‘bullshitting’. Sean here presents signs of impatience reminiscent of Gestalt therapy – he’s all for the here and now, trying to get beyond the layers of defense mechanisms designed to avoid contact. Sean is not working with the ‘transfer’ (he’s not a Freudian psychoanalyst), he’s working with the person who is there – Dasein in the Heideggerian sense. As Hans Cohn says in Existential Thought and Therapeutic Practice (1997), “On the assumption that we exist primarily in a state of relatedness, it would be meaningless to distinguish between a ‘real’ and a ‘transference’ relationship” (p.26). This also means that there’s no ‘countertransference’, only the relationship, through which the patient also helps the therapist understand how he hasn’t been able to turn the page after his wife’s death. Sean’s approach is risky: he might also be changed through this relationship. But this is exactly how we know that this is a genuine encounter – an I-Thou rather than an I-It relationship.

Therapy in the park: Sean and Will

A Liberating Encounter

“The restriction of our capacity to keep the world open for what we meet and what addresses us can be innate or the result of an unsatisfactory upbringing. It manifests itself in… ‘modes of illness’ which show impairment in our relation to certain intrinsic aspects of Being – that is, embodiment, spatiality, temporality and mood. All these disturbances encroach on the possibility of realizing the basic ontological nature of human existence: freedom and openness toward other human beings and towards all the other beings encountered” (H. Cohn, Existential Thought and Therapeutic Practice, p.18).

What takes place between Sean and Will is a genuine encounter, then. But to what extent is it a liberating one? What must Will, and Sean, be liberated from in order to be able to experience greater freedom and openness toward other human beings? And what makes it possible for the change to occur?

In Will’s case we can identify two main areas of restriction. Firstly, having grown up as an orphan and experienced abuse, his social life is limited to three childhood friends. He is unable to establish a lasting intimate relationship with a woman, and he is suspicious and defensive with whoever he meets outside of his close circle of friends. Secondly, despite his intellectual capacities, he is unwilling to take the necessary steps to fulfill his potential, since this would involve giving up his close relationships and moving to a different area. To echo Freud’s famous bon mot, his problems are related to loving and working. Sean sums it up like this: “Why is he hiding? Why is he a janitor? Why doesn’t he trust anybody? Because the first thing that ever happened to him on God’s green earth was that he was abandoned by the two people [who] were supposed to love him the most!” Of the four big existentialist themes – the inevitability of death, the need for meaning, the fear of isolation, and the need for liberty – the two main issues for Will at this stage in his life are isolation and liberty. His conflict comes from the fact that he dreads isolation (a fear of being abandoned again) whilst also craving liberty (taking responsibility and becoming the author of his own life). He knows that taking responsibility and going towards fulfilling his potential would mean having to face the risk of abandonment. So how does he manage to resolve this conflict? What makes it possible for him to gain greater liberty? The key scene is where Sean repeatedly says “It’s not your fault” until Will breaks down in tears. This is the moment where Will has a realisation that he can be in the world with other humans as he is, and still be accepted. What’s more, he realises that being abandoned is not his fault and that he doesn’t need to carry this guilt. His eyes open up to his denial, evasion, and distraction techniques, and he realises that they’re unnecessary.

On the other hand, with Sean, the existential givens he has been defending himself against are the other two of the four: death and meaning. Following the loss of his wife he needs to face the inevitability of his own death, and he needs to find meaning. No better place for that than India, he thinks.

© Tamás Szabados 2016

Tamás Szabados is a linguist, a translator, and an MA student of Clinical Psychology at the UFR d’Études Psychanalytiques of the Université de Paris.