Your complimentary articles

You’ve read two of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

The Search for Meaning

Finding Meaning in Suffering

Patrick Testa on the extraordinary hope offered by Viktor Frankl.

Psychiatric illnesses are on the rise around the world, weighing heavily on health systems already presenting barriers to access. Children and young people in particular face worsening mental health. Depression, self-harm, and suicide are occurring more frequently and at a younger age in adolescents than ever before. What can be done to alleviate this? And with all the suffering in the world, others are asking a different question: Why?

The psychiatrist Viktor Frankl stated in Man’s Search for Meaning (1946) that life is never made unbearable by circumstances, only by lack of purpose. He argued that when we struggle to find meaning in our lives when confronted with adversity, our mental health suffers, leaving a void that contributes to depression and other conditions. A primary goal of therapy should therefore be to help patients reconnect with meaning when faced with life’s challenges. As we continue to grapple with multiple crises worldwide, the lessons from Frankl and the whole field of existential psychology deserve to be revisited.

The Problem of Suffering

Frankl, a Holocaust survivor, was concerned with reconciling the existence of evil and suffering with our belief in a purpose-driven world. What’s particularly challenging to explain is what’s known as ‘natural suffering’ – events over which humans have no control, such as pandemics, natural disasters, birth defects, and cancer. An omnipotent and omnibenevolent higher power would, by definition, both have the ability and ostensibly want to design a world where these events don’t happen. Yet much suffering exists. Why?

This problem isn’t new. It has vexed theologians and philosophers for centuries, from Epicurus in ancient Greece to the Book of Job in the Old Testament to the theodicies of Saint Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. In the seventeenth century, Leibniz attempted to rationalize the imperfections of the world and the immensity of the suffering in it by contending that, despite its faults, this is still ‘the best of all possible worlds’. Voltaire famously satirized this idea in his novel Candide (1759), where we find our hero subjected to a series of catastrophes, including wars, famine, shipwrecks, plague, and the 1755 Lisbon earthquake which killed about sixty thousand people. Yet while humanity has made giant strides in improving the quality of life for many since Candide was published, suffering cannot be eradicated. It is a feature of the human condition.

Existential anxiety occurs when individuals are unable to reconcile the presence of suffering with their personal understanding of the nature of the world and our place in it. When cultural narratives are unable to provide a sufficient rationale to existential questions, this may alter a person’s worldview in profound ways and decrease their ability to cope with anxiety.

Psychologists Daryl and Sara Von Tongeren argue that when this happens, it threatens three different dimensions of meaning: coherence, significance, and purpose. This, they say, is “because suffering often feels senseless (challenging coherence), can cause people to question whether or not they matter (threatening significance), and might reveal the absurdity of life (undermining purpose), suffering cuts across all dimensions of meaning” (‘Finding Meaning Amidst COVID-19: An Existential Positive Psychology Model of Suffering’, Frontiers in Psychology 12, 2021).

What happens when we cannot find meaning? In its absence, people attempt to fill the void in many ways, for example, with the pursuit of power or pleasure. Frankl himself argued that the ‘neurotic triad’ of depression, addiction, and aggression that afflicts society is symptomatic of a widespread inability to find purpose. Friedrich Nietzsche held that ‘the will to power’ was the fundamental force behind human action. By contrast, Frankl argued that the drive to seek power was a masked effort to address (yet not necessarily satisfy) existential anxiety around questions of meaning. On this interpretation, individuals seek out power to fill what’s been missing in their lives when other avenues to find purpose have been obstructed.

People may also seek refuge in belief systems for a sense of belonging that’s absent. Frankl argued that the loss of traditional (that is, religious) values contributed to an ‘existential vacuum’ that fuelled the twentieth century’s totalitarian political movements. Communism and Fascism promised people both meaning and identity, as a worker or party member, in just the sort of way theology had done for the previous two millennia.

Totalitarian regimes can indeed in some ways resemble religions, replete as they are with their own clergy (the party), the exaltation of leaders, and the excommunication (and execution) of apostates. Generally speaking, ideology readily fills man’s drive to make sense of our world and be a part of a collective. However, Frankl thought instead that it’s only by committing to intrinsically meaningful values and goals that we’re able to find authentic fulfillment, since he believed the search for meaning was the underlying motivator of life. As a result, to cope with the experience of suffering, we must engage with existential realities directly and identify meaning. So where can we find meaning?

Two Images of the World

There’s no simple answer to this question. For Plato and others, the universe is imbued with inherent purpose: there’s an order to things in the world and an end (telos) to human life. Cultivating a set of virtues that are in harmony with this order of nature is necessary to achieve a meaningful and happy life. In particular for Plato, human purpose is closely intertwined with moving towards an understanding of the Form of the Good – the eternal standard of goodness which is the unchanging and ultimate source of justice, truth, beauty and other values.

The universe that modern science describes is ostensibly at odds with Plato’s worldview. First, the godless cosmos doesn’t have a masterplan – things just happen, sometimes bad things, without any reason at all. There’s no natural law that works to minimize either human or animal pain. Second, the scientific image of the world is descriptive, not prescriptive. That means it has a lot to say about the nature of the building blocks of the world, and less about meaning, morality, and ethics. Value claims don’t fit neatly into the empirical scaffolding of science. David Hume characterized this distinction succinctly by asking whether we can get an ought from an is. He thought you could not do so because they are “entirely different” from each other, and hence morality is not derivable from any purely scientific description of the world.

Modern neuroscience offers an elegant solution in response to Hume’s ‘is-ought’ dilemma: that value claims are emergent properties of underlying neurobiological processes. Moral decision-making is reducible to brain wiring, which through complex genetic and environmental interactions has evolved over time to favor prosocial behavior. In other words, we’ve evolved to have values and be moral.

Reductionism in various forms has been a dominant approach in the natural sciences in the last century. This strategy has produced some good results. For example, we now have a better understanding of the structure and function of the brain circuity implicated in psychiatric conditions, which allows us to develop therapeutic interventions that can more accurately target many mental illnesses. Frankl, however, argued that the attempt to explain values in purely physical terms is incomplete, as meaning is distinct, distinctly generated, and irreducible to subconscious drives. As he wrote, “There are some authors who contend that meanings and values are nothing but defense mechanisms or reaction formations… But for myself, I would not be willing to live merely for the sake of my defense mechanisms, nor would I be ready to die merely for the sake of my reaction formations” (Man’s Search for Meaning). So higher-order principles and values – the things we’re willing to live by and for, and sometimes to die for – are not adequately captured by scientific reductionism. For Frankl there exists outside our genes, instincts, drives, and environmental and social conditioning, something uniquely human, something personal, that cannot be captured in materialist reductionist thinking.

Reclaiming Meaning

In Man’s Search for Meaning Frankl offers three ways to rediscover meaning in the personal, spiritual or ‘noetic’ dimension. First, we can participate in active creation. We can start a community project, write a book, or compose music. We can build something, not because of the end, but simply for the sake of creation.

Albert Camus saw creation as an ‘absurd joy par excellence’ that mimicked the ephemeral quality of existence (The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, 1946). For example, an actor breathes life into a character for a fleeting moment, then exits the stage. The significance of an actor’s work is the performance itself and those experiencing it. The joy is in the doing. We can similarly find joy in our work. Professor Stephen Hawking for instance stated in an interview to ABC News in 2018 that his work provided meaning, and without it, his life was empty. Frankl coined the term ‘unemployment neurosis’ for depressive episodes triggered by lack of opportunities to work. Work and creativity gives us purpose and connection beyond ourselves.

A second way Frankl believed we could find meaning is through love, whether it’s love of another person, or of art or nature. Take for instance love of a novel (I’m borrowing this example from Alexander Nehamas’ book Only a Promise of Happiness, 2007). I’ve always admired F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby (1925). My interest compels me to go further into understanding it. But my continuing interest in the book isn’t to provide a final verdict on it; rather, it’s a desire to continue to interact and converse with it. The more I understand about it, the more I want to learn around it: about Fitzgerald, his life and what influenced him, and the period of the 1920s. The Great Gatsby has also pointed me to other literary works and writers that I may not have interacted with or would have understood very differently if I had not first read Fitzgerald. What I’m implying is we’re willing to change how we spend our time and other aspects of ourselves for what we love. What we’re passionate about, what we fall in love with and find meaning in – whether it’s a person, area of study, or an interest – can change the direction of our life. While this entails an element of risk, finding love can also give us a greater sense of purpose that buffers the slings and arrows we encounter as a result of being alive.

The last way to find meaning Frankl cites is by taking a stance when faced with unavoidable suffering. He argued that human life has purpose and dignity even during the most abject suffering – it has the meaning we choose to give it. Humans have a capacity to choose how we bear our burden in seemingly insurmountable conditions – and Frankl experienced some of the worst circumstances possible, living through Auschwitz and losing his father, mother, brother, and pregnant wife. Although his faith in meaning and purpose was tested, he never lost it. This tragic optimism embraces life despite its hardship.

In Frankl’s view, people have often thought about the meaning of life in the wrong way. He stated, “Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather must recognize that it is he who is asked” (Man’s Search for Meaning). He means, it’s up to us to find meaning to our lives in any given circumstance.

Frankl is not saying we shouldn’t try to alleviate suffering. We should. And when we see injustice, it’s our responsibility to try to rectify it. But he reminds us that courage and honor can be found even in the darkest times. And in misfortune, there can be hope for the future.

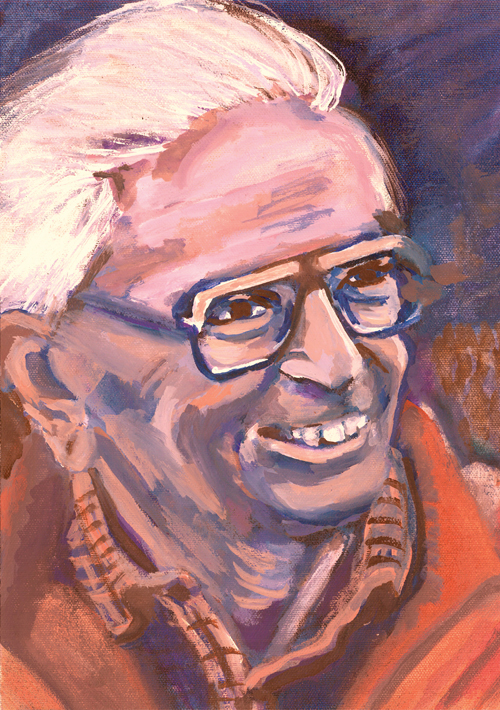

Viktor Frankl by Gail Campbell

Meaningful Therapy

Finding meaning was also central to Frankl’s therapeutic approach, known as logotherapy. The goal of logotherapy is to guide patients toward finding meaning in order to better cope with adversity. It’s built on first helping us recognize and process our feelings concerning major existential questions related to purpose, choice, and loss. For example, during a crisis, Frankl teaches us to focus on only the things we can control: our thoughts, actions, and attitude. Suffering can make us feel alone and separated from the world and from others. Yet we can reframe our experience, even during extraordinary times, as a common attribute of being human, and so change our thinking about it. We can then work on reconnecting with those things we value.

One useful exercise to clarify and prioritize meaningful values, is to write down a list of what’s most important in your life, and rank areas of focus. This is a useful practice because knowing and consistently reminding ourselves what matters most in our lives – what gives us purpose – points us toward a psychological true north. It can serve as a guide that can inform our decisions. The objective of a ‘core values’ exercise is to help individuals commit to goals that are unique to them, which only they can fulfill. It also encourages us to embody the values we have selected in the choices we make each day. Examples of core values include family life, a work ethic, achievement, personal learning/growth, faith, service, adventure, fun, and health. There are many ways to rank these dimensions of meaning, and all are valid. What’s important is the values we select have personal meaning to us.

Discovering meaning can also serve as a roadmap for navigating difficult times. Frankl, for example, maintained a vision for how he could use his dreadful experience in the concentration camps to help others. This hope sustained him in those desperate circumstances. And further research has vindicated Frankl’s idea that the ability to identify meaning when confronting hardship improves resilience and recovery (see for example ‘Purpose in life predicts better emotional recovery from negative stimuli’, PLOS One, 8(11), Schaefer, S., et al., 2013).

We live in a time of great upheaval, where the ties that held us together as communities continue to unravel and a future that perhaps once seemed clear appears increasingly uncertain. So identifying the meaning that is intrinsically important to each of us is not an esoteric or trivial pursuit. Rather, finding our why is critical for our own mental health and that of our communities.

Suffering is a part of the human experience, but when faced with adversity, we all have the potential to find courage, hope, and ultimately a meaning that allows us to move forward in spite of the pain. Victor Frankl’s work is powerful because, despite the world’s flaws, and while knowing the worst of the human condition, it encourages us to say ‘yes’ to life.

© Patrick Testa 2024

Patrick Testa is a psychiatric clinician who treats patients with mental health conditions across the lifespan. He holds a BA in philosophy and political science.