Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Doughnut Economics

David Howard on restoring balance to an unstable world.

Is it still possible for us to live a good life while avoiding climate catastrophe? How could society be organised to create the conditions for that, and so they are inherited by succeeding generations? If existing social and economic structures have led us to this looming crisis, what will be demanded of our successors, and what reasons for hope can we give?

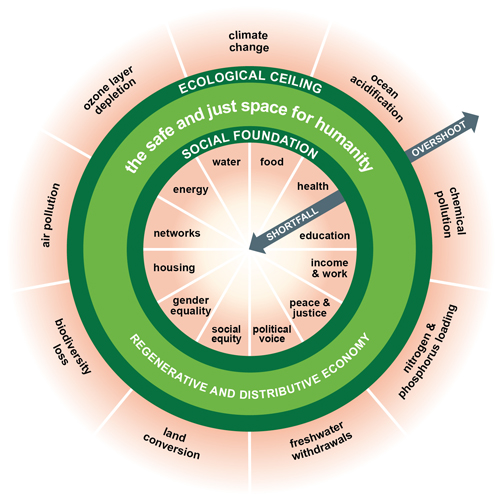

Warnings that the world’s economic trajectory is unsustainable are not new. Fifty years ago, Donella Meadows and her co-authors pointed out in detail in The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind (1972) that there were ‘limits to growth’. The steady accumulation of data since then has not changed that message, but only given it added urgency. The concept of economic limits has also been reinforced by the idea of ‘planetary boundaries’, first proposed in 2009 by Johan Rockström (then Director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre) alongside a group of twenty-eight internationally-renowned scientists. Their pie chart showing nine global boundaries, including climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution, provided a clear scientifically-determined picture of the dangers threatening ‘a safe operating space for humanity’. The group’s updated 2023 report showed that six of the nine safety boundaries have now been transgressed, and the pressure is increasing. The world is not acting quickly or effectively enough for its own safety. Only in respect of ozone layer depletion have things moved in the right direction.

Scanning The Horizon

© Paul Gregory 2024

The scientific evidence, then, has been clear for some time; but the wisdom required of political leaders – and, indeed, of the societies they serve – has been sadly lacking. Short-term priorities have been the rule, and the stop-start journey to Net Zero and a more ecologically secure future has been bedevilled by issues of justice and fairness, for climate change brings into sharp relief the inequalities that exist both within and between different societies. Environmental turbulence both is and will continue to be felt most keenly by the peoples of the developing world who are least responsible for its creation and who are also least equipped, both in terms of finance and social structures, to deal with its effects, since mitigation will be expensive. At the same time, poorer nations justifiably protest the imposition of measures that seem to stymie their progress towards the level of affluence enjoyed by the developed world. Investing in solar energy is a hard sell to a subsistence farmer.

Questions of equity also arise within the developed world. All too often the preferred solutions of green campaigners seem almost other-worldly. Electric vehicles are beyond the budgets of many ordinary workers; organic, home-grown food is too expensive for a family struggling to make ends meet; putting in adequate insulation to ensure a liveable temperature, let alone installing a heat pump, is not possible for those in poverty, or one pay cheque away from bankruptcy. So common demands to move towards a greener economy can appear unreasonable, as they expose the debilitating inequalities which scar so many societies. This has led many to argue that greater equality is, in fact, a pre-condition for living within our planetary boundaries: the one cannot be achieved without the other.

A Fresh Proposal

To bring together the demands of ecological limits with those of social justice, Kate Raworth launched the quirkily named ‘Doughnut Economics’ in her 2017 book of that title. In it she combined planetary boundaries with the idea of a social foundation – a level of life below which no person should be allowed to fall. Here, safety and justice become part of the same enterprise. By adding an inner ring to the Rockström piechart, Raworth asked us to visualise the issues in an integrated manner. This is a challenge particularly for those who wish to compartmentalise (and then often sideline) the problems under discussion – a criticism of successive climate conferences.

The twelve segments of the social foundation inner ring are derived from the priorities specified in the United Nations’ 2015 Sustainable Development Goals. The task is to respect the limits of the natural world while ensuring all are provided for. Overshooting the boundaries brings climate disaster; undershooting on social needs deprives people of a sustainable and dignified life. Balance is all: the model claims ‘a safe and just space for humanity’ between the extremes – a sort of golden mean which seeks to avoid both the ecologically destructive excesses of global consumer capitalism and the inequalities which undermine any decent society, by denying, particularly to the poor, access to a fair share of the planet’s wealth. Earlier economic models tend to assume endless economic growth and therefore are predicated on insatiable consumerism and acquisitiveness. Policies based on these models are destroying the ecosphere on which we depend, and also condemning the least favoured to lives which are either sub-optimal or endangered. The idea that the world has seen more and more of its population lifted out of abject poverty in the last decades runs headlong into the facts of the degradation of the natural world and the increasing gap between rich and poor. For Doughnut Economics, however, environmental and social health are two sides of the same coin, and it is only by tackling both that societies could enable everyone to flourish in a safe and just space.

Doughnut Economic Model © Doughnut Economics 2017 Creative Commons 4

Personal & Social Challenges

To answer the questions posed at the start of this article, the Doughnut Economics model imagines a transformation in thinking: addressing the problems caused by overshooting planetary boundaries has to be matched by and linked to serious work on the economic and political dimensions required by sustainable development. So environmental concerns are not just about a search for technological solutions (though many of these are needed and are to be welcomed), but about the way human beings live together, and how they respond to the challenges they face, both individually and in communities. The Doughnut framework represents a meeting of obligations to each other and to future generation; it is also a challenge for people to take wider responsibility for their actions. Social well-being depends on the application of human values.

In confronting traditional economic models, which are both unsustainable and inequitable, Raworth challenges societies to reset their thinking and look for ways of moving from a ‘degenerative’ and ‘linear’ economy (motto: Take – Make – Use – Lose) to one that’s cyclical and ‘regenerative’. Her proposal for an Economist’s Oath (modelled on the Hippocratic Oath for doctors) also introduces an ethical dimension, by suggesting a set of moral principles for economic policy-making. This challenges a widespread view of economics which is fixated on the single measure of Gross Domestic Product. Doughnut Economics is instead about what helps people in all societies to thrive – implying that ‘wealth’ is more than just capital accumulation. There is enough wealth for all, if only we distribute it more equitably; and also take seriously the realisation that what makes us wealthy cannot always be measured in terms of GDP. Rather, in more holistic terms, ‘wealth’ is whatever helps us to thrive: from good schools to clean air; from an effective health service to good infrastructure; from security, to freedom to think and speak one’s mind; and companionship. Given the assurance that basic needs are met, it is this sort of wealth which promotes well-being.

The first principle of the proposed Economist’s Oath is to ‘Act in service to human prosperity in a flourishing web of life’; the second is to ‘Respect autonomy in the communities… by requiring their engagement and consent’; the third is to ‘Be prudential in policymaking, seeking to minimise the risk of harm’; the fourth is to ‘Work with humility’. Adopting these principles would rule out of court a number of currently active economic policies – any proposal which enriches some at the cost of the absolute immiseration of others; any proposal which prioritises short-term gain over long-term environmental damage; any proposal which favours current prosperity over the absolute well-being of future generations; indeed, any economic proposal carrying the risk of grave harm, whether to people or to the environment.

Challenges To The Challenge

Naturally, general acceptance and application of this new way of thinking faces serious challenges. We’ll consider two here.

Firstly there’s the issue of psychology. The doctrine that it’s people’s duty to keep on purchasing so that the economy can continue to grow has tapped into the natural acquisitiveness of human beings to the extent that many now think that they have a right to expect more and more goods. Moralists down the ages have pointed out, in stringent terms, the psychological consequences of untrammelled desire. But stern warnings from pulpits and op-ed pieces are too easily ignored when faced with media-promoted temptations of consumption and the itch of status anxiety: ‘Give me temperance, but not yet!’

Social cooperation is always at its strongest when a society is faced with an existential threat from outside. Although the majority of people now accept that climate change is real, there is little appetite for measures that are seen to lead to a reduction in living standards, even if there are benefits for society. In the eyes of most people, such benefits remain theoretical, even undesirable. Activists may have given up flying; but most people want their holiday in the sun.

The second challenge is that of time. Promotion of a new economic model is firstly a matter of winning hearts and minds – a long and arduous process – and secondly, working out in detail the implications for communities. But time is relatively short, and shrinking. There is every chance that some processes of climate change are even now irreversible. The emergency may not hit home until it’s on one’s doorstep; and by then it will be too late to prevent most of the effects. You cannot build flood defences when the water’s already seeping under the front door! By the time the Doughnut model or any equivalent measures have gained any significant traction, the world will be a very different place. Nudges towards different habits are valid, and valuable, but do not address the urgency of the situation. As the climate increasingly reshapes itself, and the political context moves towards national self-interest (and sometimes even old-fashioned nationalism), the opportunity for effective international agreement recedes, and cooperation, founded on an acceptance of human interdependence, becomes the exception rather than the rule.

Tentative Conclusions

What is left then, when the challenges seem so overwhelming? As many of those committed to raising awareness and promoting change have found, it is their very activism which holds despair at bay. A retreat into passive acceptance leads only to depression. What can remain is a form of radical hope. One does what is right in the moment: living within limits, in line with the demands of the planet and of our humanity; and one sets an example of how life can be different without boastfulness or virtue-signalling. One continues to work for and advocate the changes necessary for the establishment of a good society where all can flourish. One lives in the belief that, whatever climate change throws at the world, there will still be a world, and that one can and must rebuild on a sounder foundation. The claims of intergenerational justice demand nothing less: the aim is to be good ancestors. One lives in hope that examples of temperance, of courage, of wisdom, and of justice, will provide that foundation.

In its overarching concern to conserve the intricate web of life, and at the same time promote the well-being of all peoples, both now and in the future, perhaps the biggest virtue of Doughnut Economics is to inspire that radical hope.

© David Howard 2024

David Howard is a retired headteacher, and Chair of the U3A Philosophy Group in Church Stretton, Shropshire.