Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Thoughts on Thought

Iain McGilchrist’s Naturalized Metaphysics

Rogério Severo looks at the brain to see the world anew.

It seems there was a time when metaphysicians were all of a single species. Now they appear to make up at least two. Of the newer kind is the psychiatrist and neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist, most famous for The Master and His Emissary (2009). His work is a notable contribution to what one may call ‘naturalized metaphysics’. It differs from classical metaphysics in that it justifies its statements empirically rather than by reasoning alone. Unlike traditional metaphysics, it grounds its claims about the nature of reality on the findings of natural science.

In modern philosophy, Willard Quine (1908-2000) can be said to be the father of naturalized metaphysics. A salient aspect of Quine’s work was his defense of a materialist worldview, based on what he viewed as the best understanding of the science of his time. This was one of the topics of his main work, Word and Object, originally published in 1960. Yet over the last few decades, some of the philosophical attempts at utilizing the findings of natural science have followed different paths, leading to metaphysical theories that are not materialist. The philosophy of mind of David Chalmers, for example, can be included in that category. In the case of McGilchrist, claims about the most general traits of reality are directly grounded on empirical findings, issuing straight from his own laboratory research on distinctions between the brain’s hemispheres.

It is irrelevant that McGilchrist is not a professional philosopher. The fact that most current philosophy is done in university philosophy departments is a modern idiosyncrasy. In earlier periods philosophy was less compartmentalised. But we seem to be witnessing something of a return to that earlier configuration, when philosophy was not contained by any formal academic boundaries. The essays on perspectivism by anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro; the works of biologist E.O. Wilson or linguist Steven Pinker on human nature; those on moral foundations by the psychologist Jonathan Haidt; as well those on equality, justice and freedom by the economist Amartya Sen, can all be viewed as examples of this trend. The confluence of goals and methods in philosophy and science is a basic feature of naturalism in philosophy; and naturalism is a main feature of a sizable portion of the philosophy now being done. But let’s focus on McGilchrist’s work in particular.

Focusing on Brain Hemispheres

McGilchrist’s staring point in his research is the psychiatry of brain hemispheres. Over the last four decades there have been significant developments in understanding of the way the hemispheres work and how they interact. Initially it was assumed that there was a simple differentiation of functions: language and reasoning would be processed mainly in the left hemisphere, whereas emotions and vision were handled by the right brain hemisphere of many people (exceptions include most left-handed people). This division of labour among the hemispheres seemed to be indicated by the behaviour of people who had undergone split brain surgery in the 1960s and 70s – a technique used to treat exceptionally acute and debilitating cases of epilepsy, in which the nerve fibres linking the two hemispheres are severed. Later, however, it was discovered that there is no clear division of labour between left and right brain. Language and emotions are processed by both hemispheres, as are abstract reasoning and vision, and likewise for most other functions.

This brought up a kind of riddle: Why is it then that we have two distinct hemispheres? Not only us humans, but all mammals, as well as fish, birds, and reptiles. And what are we to make of the fact that the division of brain hemispheres has became more accentuated over the course of evolution, not less?

McGilchrist lays out his hypothesis for the evolution of brain hemispheres in the first part of The Master and His Emissary, and again in the first part of his 2021 book The Matter with Things. There are two mental activities essential for the survival of animals, and they must be carried out concurrently. One is monitoring the environment for risks and opportunities (predators, food, sexual partners, shelter, etc.). The other consists in classifying then acting upon a risk or an opportunity once it has presented itself. This requires a focused attention that isolates that particular thing or event from the overall context, allowing for its specification and manipulation – such as picking up food and eating it.

These two basic activities require two kinds of attention. The first is wider and less focused, open to the environment as a whole and to what is unknown about it; the second is focused on something known and categorised, detached from its context and mentally represented in isolation from the environment. An illustration offered by McGilchrist is that of a bird scanning a field without focusing its attention on anything specific. Then, once it sees something on the ground that looks like a seed, its attention shifts and becomes more narrowly focused. Because the eyes of most birds are located on the sides of their heads, they must turn their heads one way or the other to engage one eye or the other. Scanning the environment for risks and opportunities, birds tend to use mostly their left eye, which is linked more strongly to the right hemisphere of their brains. Once something potentially edible is found, though, the bird will turn its head and look at it with the right eye, which is linked to the left hemisphere. The attention of the left hemisphere allows for the mental detachment of that seed from the environment and its categorization. It’s this kind of attention that’s used when coordinating eye and beak to grasp just that seed, and not any gravel that might be next to it on the ground.

The wider attention is more holistic and situates an individual in their overall context; it is open to unknown risks and potentials. The more narrowly-focused attention abstracts from the wider context, allowing for classification, and is thus about what is already known. This is an asymmetry in the workings of the two hemispheres. The kind of attention produced by the left hemisphere evolved to represent, map, and schematise the reality that’s first presented to the contextualized attention of the right hemisphere. In this way, the right hemisphere comprehends and provides a sense of meaning to the representations of the left hemisphere. The right hemisphere is the master, the left its emissary – just as McGilchrist suggests in the title of his book.

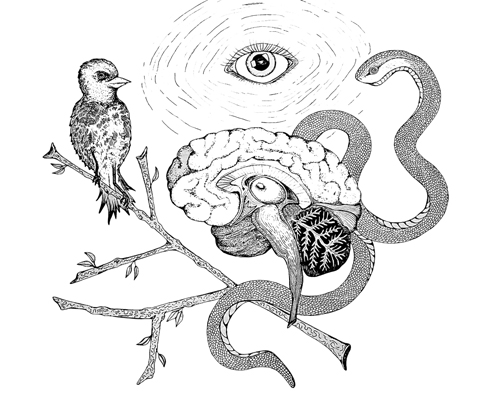

Perceptions by Abigail Vettese

Image © Abigail Vettese 2023 Instagram: @theshapeofsanctum Website: abigailvetteseart.com

Splitting the Human Mind

In the case of human beings, brain lateralization has several other features, since our imagination, reflection, reasoning, and speech are lateralised vastly more than in other species. But with us, too, the processing can be either more focused, decontextualized and abstract; or else more holistic, embodied, and specific.

Take language, for example. It can be used in a more precise and technical manner, to identify, classify, and describe things already known; or it can be used in a more ambiguous, metaphorical and open way – as in humor, poetry, metaphors, and the conveying of feelings and possibilities. The former kind, typical of the language of the sciences and the impersonal language of bureaucracy, is useful for schematizing and categorizing, tends to disregard singularities, and treats objects as instances of universal concepts. The latter kind tends to present specific, concrete situations, emphasizing the relations in a given context, and acknowledging what is unique, transient, personal, and partially unknown in whatever presents itself.

According to McGilchrist, the more technical, abstract uses of language make sense to us only within the more general context of metaphorical language that links abstract concepts to the particularities of our bodies and their environments. A similar point had already been made by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson in their well-known Metaphors We Live By (1980), where they say that metaphors are not mere supplements of literal uses of language. Quite the contrary, they make up a basic use of language, since only metaphors can ground the meanings of abstract universal concepts in our particular experiences.

The kinds of attention brought to bear by each brain hemisphere induce perspectives or views of the world that differ yet complement each other. The right hemisphere tends to view the world as a flux: as inconstant, paradoxical, made up not of things and machines but of processes and organisms. It tends to consider implicit and hidden aspects of reality, and to consider risks and potentials. It also tends to have a more aesthetic and spiritual appreciation of events, and to be more melancholic and pessimistic. The left hemisphere, on the other hand, tends to appreciate mechanisms, and to view the world as a representation or picture: something fixed, involving boxed-in categories. It tends to pay more attention to manifest aspects of reality and disregard whatever might be hidden. Since it tends to disregard the unknown and the possibility of mistakes and ambiguities, it also tends to be more self-confident and optimistic about its own capacities. These two kinds of attention complement each other and are important both for our integration into the environment by making sense of what we see and do (right hemisphere), and for manipulating and grasping things already known and conceptualised (left hemisphere).

McGilchrist cites ample empirical research showing that individuals who have suffered lesions (damage) in one of the hemispheres show deficiencies in the corresponding type of attention. There’s also a lot of neuroscientific evidence with respect to the asymmetry of the two hemispheres. People whose hemispherical functions are excessively symmetrical – as is the case with many schizophrenics – show behaviour typical of people who have a right hemisphere deficit. This reveals that the normal working of the brain is asymmetrical and, generally speaking, guided by the right hemisphere. The world of a schizophrenic is fragmented, lacking continuity and fluidity. Objects and events are more isolated one from another, and their language is more literal. This shows, McGilchrist argues, that a healthy and balanced working of the brain is asymmetrical, with the right hemisphere having the first and the last word, so to speak. The right is, generally speaking, the hemisphere that evolved to understand: to make sense and integrate what’s experienced within the wider context of one’s life. The left hemisphere is more a sort of servant, useful for specific tasks, but unable to comprehend the whole.

The View From Each Hemisphere

According to McGilchrist, there may be a preponderance of perspectives and worldviews characteristically induced by one or other hemisphere in a given historical period. The second part of The Master and His Emissary lays out this hypotheses for different cultural periods of Western history. It’s unclear why it happens, and the author offers no explanation: he presents it simply as a fact that a culture might show signs of being more preponderantly aligning with the attention and perspective of one brain hemisphere or the other at different periods. For instance, both in classical Greece and during the Renaissance, there would have been a preponderance of worldviews typically induced by the right hemisphere. However, in scholastically-inclined Eleventh and Twelfth Century Europe, as well in the present analytical times, the opposite is the case: most contemporary culture (art, philosophy, science, technology, social bonds, bureaucracies) tends to conceive the world in technical, mechanical, and impersonal terms.

McGilchrist draws attention to how some contemporary conceptual art and the geometrical abstractions in some painting have a kinship to the kinds of drawings and descriptions of the world made by patients who have suffered damage to the right hemisphere. These too tend to be schematic, two-dimensional, geometric. This contrasts starkly with the kinds of drawings and descriptions made by patients who have suffered left hemisphere lesions. These tend to be more organic, fluid, three-dimensional and not schematic. This can also be contrasted with a good deal of twentieth century analytic philosophy, which deliberately shuns everything ambiguous, implicit, and metaphorical. And here we have some indication of McGilchrist’s motivations: as a lover of poetry and the arts, he regards the instrumentalist culture that’s become prevalent among us as a kind of insanity.

The Matter With Things

Whereas in The Master and His Emissary McGilchrist drew a conclusion concerning philosophy of history and culture from the findings of brain hemisphere research, in The Matter With Things he is much more ambitious.

This is a work that impresses not only because of its length (two volumes of 750 pages each) and erudition (the references section at the end has more than 150 pages), but also because of its intellectual scope. The intent is to comprehend the most general traits of reality as a whole.

The guiding star of McGilchrist’s reasoning in The Matter With Things is that our cognitive access to the world is mediated by consciousness, which varies according to our attention. Therefore what we conceive as being real varies according to the kind of attention prevailing in us at that moment. Different kinds of attention bring forth different aspects of the world, and thus induce different conceptions of the world – in effect, creating different metaphysics. When the kind of attention yielded by the left hemisphere prevails, we become more aware of and give more emphasis to what is static, fixed, discrete, mechanical, and geometric: we focus on what is there and how it works. Hence, the materialist metaphysics that have been abundant since the second half of the last century typically issue from the focused attention that extracts from the wider context and seeks to categorise whatever it’s focused on. The right hemisphere, on the contrary, tends to view the world in terms of continuous, holistic processes: it tends to be more aware of what is unknown, and tends to remain open to what is paradoxical and hidden. It tends to give more emphasis to relations than to what is related, and to the meaning of whatever presents itself than to its functions, and is thus more able to comprehend reality as a whole.

So is the world we live in made up of things or of processes? Mechanisms, or organisms? Is the world the sum of its parts, or are the parts mere aspects of the whole? Moreover, are values aspects of reality, or are they cultural constructions? Is the religious impulse some sort of wishful thinking, or is it a basic feature of human nature? One implication of McGilchrist’s work is that these sorts of fundamental question are not addressed from a neutral point of view, independent of how we attend to the world. Sure, we can imagine things from perspectives that differ from the perspective we have now, but to do so we must use the mental resources we have. There is no ‘cosmic exile’, as Quine once wrote, from which we might philosophise about fundamental questions. We cannot step aside from our minds to inspect the world and ourselves. We can only answer questions from one or another perspective. And if we address them from a left hemisphere perspective we will come up with answers that are quite unlike the ones we will get from a right hemisphere perspective.

However, we can reflect on what we already know about ourselves and the world, and thus correct, and change, our views. Considering then what we do know about the kinds of attention produced by the brain hemispheres, and the kinds of worldviews they tend to induce, we have reasons (evidence, if you like) opposing metaphysical materialism.

A Mind’s Perspective on Minds

Iain McGilchrist

© Rebel Wisdom 2018 Creative Commons 3.0

The asymmetric working of the hemispheres indicates that to make sense of our experiences as a whole, the right hemisphere has to be in charge and have the last word. The left hemisphere is good at instrumental reasoning, at formulating schemata and manipulating concepts, but not at making sense of them. In Parts Two and Three of The Matter With Things, McGilchrist indicates how we might find out about the world by giving prevalence to a right hemisphere perspective, and how the world looks when viewed from such a perspective. The implied conclusion, as I said, is an anti-materialist metaphysics. But those are just implications, not proofs or demonstrations. Uncertainty, after all, is itself a feature of the worldview induced by the right hemisphere.

A materialist or physicalist metaphysics says that the world is made up purely of physical objects devoid of intrinsic value or purpose, and that all we know about value, beauty, or spirituality reduces to the interaction of particles and forces. According to McGilchrist, such a metaphysics only makes sense to someone whose right hemisphere has been positively muffled. That view might be useful for particular purposes. However, the purpose for which it is useful can only be comprehended in terms that cannot itself be reduced to physicalism. In individuals whose brain hemispheres cooperate in a healthy and asymmetric manner – that is, in whom the right hemisphere plays the role of the ‘master’ – there always seems something nonsensical about a materialist metaphysics when it’s not viewed as merely useful for certain purposes, but taken to be about what there ultimately is.

The argument here is not that things are a certain way because we conceive them to be so (which would be something like philosophical idealism), but that we can conceive the world variously, and some of those conceptions are more adequate for the narrower purposes of manipulation, control, and explanation of what we already know and have catalogued, whereas others are more adequate for comprehending life and the world as a whole, always somewhat unknown and often paradoxical, and yet beautiful, valuable, and meaningful. The argument is then that if we take seriously what we already know about the kinds of attention produced by the brain hemispheres, our general metaphysics will tend to be a metaphysics of processes, values, and spirituality rather than a metaphysics of objects, causes, and geometric schemata. (McGilchrist also claims that this isn’t something that can be understood thoroughly literally, since literal language is only useful for certain narrow purposes!)

Therefore, starting from observations and findings that are strictly empirical, McGilchrist leads us, by way of considerations that are scientific, together with intuitions and reflective imagination (also intrinsic to scientific research) to the conclusion that the materialist metaphysics that prevailed in the twentieth century is mistaken in its most fundamental claims. In other words, we have in McGilchrist’s works a kind of empirical foundation (though surely also more than that) for the truth of these Lines composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey:

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

(William Wordsworth, 1798)

© Rogério Severo 2024

Rogério Severo is Associate Professor of Philosophy at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil).