Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

The Return of God?

A Critique of Pure Atheism

Andrew Likoudis questions the basis of some popular atheist arguments.

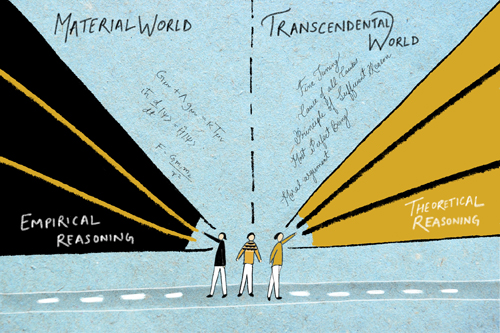

Proving or disproving the existence of God is predominantly a matter for reason, rather than for scientific enquiry. What are needed are deductive arguments that try to explain God, and, through logical inference, his relation to the world.

It would be an error to limit truth-seeking to empiricism (science) alone. Modern atheism, whenever it insists upon using empiricism as an all-purpose tool for knowledge, does so in pursuit of the exact issue that transcends empiricism, since God is outside the universe, not in it. That is to say, God’s intelligence is reflected in his creation, but is not always perceived, or able to be used as verifiable evidence. And what has been said by many theologians also needs to be fully grasped: that God is completely distinct from anything we could try to use to classify him. Indeed, Aquinas describes God in Latin as totalliter aliter – ‘totally other’ – and therefore outside of our capacity to fully grasp.

Leap of Faith © Susan Auletta 2024 Please visit instagram.com/sm_Auletta/

It’s true that human limitations make it difficult to prove, or understand, higher truths. Fortunately, it’s possible at least to begin to describe aspects of God that are comprehensible through human faculties. For instance, God is a pure perfect intelligence – almost by definition as ‘the personal creator’. If he were only sub-optimally intelligent, then he would not be infinite, and so not God, at least in the traditional monotheistic sense.

Since God is not only pure intellect but the ground of being itself (which cannot be quantitatively analyzed, of course), rather than a physical object within the universe, seeking material scientific proof does a disservice to the discussion of God’s existence. In questioning his existence, we have to let ourselves be led mainly by the intellect and critical thinking instead, and not let ourselves be cheated by those who make the category error of trying to box God into empirical data. Therefore, the main purpose of this essay is to show why we should accept rational arguments for God’s existence without strictly empirical proofs: when it comes down to it, proving the existence of God is not about presenting scientific evidence, but about demonstrating his existence by methods such as the moral, cosmological, or ontological arguments.

When science fails to provide a conclusive answer to the God question, as it must, then science-reliant atheists often adopt a blind faith stance, abandoning any semblance of self-regulatory skepticism about their position. I would go further. With scientific testing being the wrong method for addressing the question of God’s existence or non-existence, and rationality given its due, holding onto a positive belief in God’s non-existence is a pure act of the will – as I say, one of blind faith, in defiance of logic and reason. But if rational analysis is used instead, the atheist will find himself working against the overwhelming philosophical and historical evidence for God’s existence.

People sometimes claim that philosophy is a ‘dead’ area of study, in which ancient points are endlessly rehashed. This could not be further from the truth. As science and the humanities develop and grow, so does philosophy, which incorporates what it derives from those developments. And although some still do not consider philosophy a worthwhile endeavor, it remains the study of why things matter. There’s an old trope: a scientist asks a philosopher why philosophy matters. The philosopher responds by asking him why science matters. As the scientist begins to answer, the philosopher interrupts and says, “And now we’re doing philosophy!”

Up until the twentieth century, the tradition in Western civilization was that the wider populace held that God exists. This put the ball in the court of the people trying to overturn what might be considered the accepted position. But since the Enlightenment, philosophers started deconstructing things that would have previously either been taken for granted, or at least given the benefit of the doubt. This is not to denigrate the Enlightenment or similar periods, which are rightly to be commended for producing magnificent methods of critical thinking. As with all epochs, however, it was not without its deficiencies. In their most radical expressions, the Enlightenment produced extreme skepticism. This exaggerated practice, coupled with an emphasis on empirical proof, led to the abandonment of belief in God with what could very well be called insufficient reason, since using extreme skepticism to disprove God’s existence should also disprove the reasoning by which one came to that conclusion!

These extreme methods and subsequent ‘conclusions’ pose a problem, since God can be convincingly argued for rationally. However, due to the permeation of a lopsided scientism through Western culture, one big issue faced by the theist today is that people seem unable to accept anything less than empirical proof for the existence of God. This is ironic considering that they will accept for instance truths of beauty or morality, or perhaps the words of a significant other who says ‘I love you’, despite these things not being empirically provable either.

Atheism or Agnosticism?

Aristotle, Plato and the rest of the Ancient Greeks who laid the bedrock for philosophy each had a different approach, some being more skeptical, others more empirical, and still others concerned with rationalistic areas such as ethics or the forms of knowledge. Fast-forward to the Medieval period and you have figures such as Saint Thomas Aquinas with his Summa Theologica (1274), which was as much a philosophical as a theological treatise (or rather, collection of treatises). He was probably the most influential in conceiving arguments for God’s existence. How atheism could have surfaced in such a major way after such a towering figure as Aquinas is one of the world’s great mysteries to me!

Agnosticism seems a much more reasonable position, given that a burden of proof rests on the atheist but not the agnostic. In some scenarios, the burden of proof also rests on the deist or theist instead; but at least the believer has positive arguments that demonstrate God’s existence, whereas the atheist has the almost insurmountable task of making a positive case for the non-existence of something; and so it turns out that they’re mostly only able to argue against presupposing God’s existence. But let’s be clear that arguing against arguments for God’s existence is not the same thing as demonstrating his non-existence. The latter is a much harder case to make, since it entails at the very least the task of warding off every argument that might plausibly demonstrate his existence. A firm atheistic worldview requires a strict dis-proof – which, considering the centuries of literature on this subject, seems impossibly elusive. But if he has not managed to provide this disproof, then he really cannot consider himself a true atheist – that is, one with a firm and demonstrated disbelief. Rather, he is an agnostic (which means, one without knowledge of God’s existence or non-existence) – unless, that is, he is willing to take a leap of faith to get to his atheism, which, considering the circumstances, seems both ironic, and riskier than a leap of faith to get to the contrary position. Indeed, it seems to me that positive atheism requires more faith than the believer requires for his belief. True atheism, in the sense of the positive belief that there is no God or gods (that is, a belief that there is no God, in contrast to having no belief that there is a God), presupposes that one considers oneself irrefutably unconvinced, whereas theism only requires belief ‘the size of a mustard seed’ (Luke 17:5-6). So it’s not that the theist has an empirical or logical proof of God’s existence, but rather, that he has taken a rational leap into that belief based on positive arguments for God (of which there are many), thus giving assent to a proposition that has good standing, epistemologically speaking, in contrast to those who just blindly disbelieve.

As a side note, I think that people prefer to consider themselves atheists when they’re leaning towards God’s non-existence, and to consider themselves agnostic when they’re closer to being middle-of-the-road or undecided but not antagonistic toward the pro-God arguments. It also occurs to me that this decision to label those who simply lack a belief in God an ‘atheist’ rather than an ‘agnostic’ is simply an error. If one does not have a positive disbelief, that is, if one has left the pro-God arguments unanswered and ignored, then if one cares enough to be intellectually honest, the only option left is to admit at least the possibility of a deity – which places one in the agnostic camp.

© Vikas Beniwal 2024. Please visit his Instagram @wisdomillustrations

The Solution

Rationalism is the road by which to approach the question of the existence of God, through a philosophical process of questioning and reasoning. Empiricism is not the same road, and should not be applied when trying to prove or disprove God’s existence, since an intellectually honest and comprehensive conception of God defines him as transcendent of the natural order, which proceeds from him, rather than he from it, and empiricism will always come up short when seeking to disprove the existence of a transcendent being, as it is strictly limited to the study of the natural order. Positive proof of the non-existence of God, therefore, cannot be achieved through the scientific method. God’s existence (or non-existence) is, instead, ascertained through the domain of the purely rational, or through considering the historical evidence – for instance for the resurrection of Christ.

Far too often – but hopefully by hapless error rather than through intellectual dishonesty – seekers ‘jump the rails’ from empiricism to rationalism, attempting to use an empirical method to come to a purely rationalistic conclusion. While empiricism can serve the rationalistic process to a point, such a leap from the empirical method to a purely rationalistic conclusion is akin to trying to use flour, butter, sugar, and eggs to build a computer. But when one finally can admit that empiricism is off the table, proving God’s non-existence through rationalism represents an unbearable burden. In light of the rational evidence, then, we have a new question: To believe or not to believe?

I think it comes down to whether or not we should believe that any of the reasons given for belief in God are of any importance, or indeed whether they matter. But as Søren Kierkegaard might recommend, we have permission to consult not just the head, but also the heart.

Josef Pieper, arguably one of the most important theologians of the twentieth century, schooled in the thought of the Greeks as well as of St Thomas, would say that “love is the simplest reality”, of which there is no more basic explanation than the idea itself. To try to qualify the word ‘love’ is to complicate it; but what love means, simply put, is, ‘I think it’s good that you exist’. But love is what many people would say gives fundamental meaning to their lives – perhaps just because it says something to the effect of ‘It’s good that you exist’. Yet God is described as ‘love’ in 1 John 4:8: “God is love; and he that dwelleth in love dwelleth in God, and God in him”. Among other things, this means “God saw all that he had made, and it was very good” (Gen 1:31).

John Henry Newman, a nineteenth century theologian, was an elegant and illustrious writer, hailed by the great James Joyce as his superior in his grasp of English prose. When Joyce was praised for being ‘the most accomplished writer of English’, he responded by saying, referring to Newman, “Nobody has ever written English prose that can be compared with that of a prince of the only true Church.” Cardinal Newman wrote a treatise called An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent (1870). This essay described how the mind naturally synthesizes staggeringly large amounts of data every day, and comes to rational conclusions with such immediacy and accuracy that almost no concerted effort of thought is required on the part of the individual. It’s an in-born heuristic tool, both useful and necessary for our survival. For an example: if someone receives a call while at work from a number they don’t know, and the speaker identifies himself as a police officer reporting that their house has been broken into, and mentions their address, they will usually immediately trust that he is in fact a police officer, and that he is telling the truth, without any positive proof of either of these things. Newman terms this phenomenon of instant rational synthesis the ‘illative sense’. It’s a process we engage with, day in, day out. Why would a belief in God be a bridge too far in this regard, when in fact we practice this intuitive behavior so regularly and successfully? The question is whether we will allow the seemingly self-evident truths of love to resonate with us and fill us with an understanding similar to what we might label a ‘justification’ for our existence – which, in many ways is what we all desperately seek, knowingly or unknowingly. This seems to be the real query here – whether we recognise the transcendent truth of love – and it’s up to each individual to give a response to it. Do we believe in ‘unprovable love’, or will we continue seeking an empirically verifiable answer to a question that’s really not first posed by the rational head, but by the sometimes irrational, or, one could say, super-rational, heart?

© Andrew Likoudis 2024

Andrew Likoudis is the president of the Likoudis Legacy Foundation, an ecumenical research foundation. He is also the editor of six books, and studies communication at Towson University.

Three Philosophical Arguments For God

These are the philosophical arguments for God mentioned in the article:

• The Moral Argument

This argues that God is the only viable explanation for objective morality. It goes like this: (1) Without God there are no grounds for objective morality, or for moral obligation; (2) But morality is objective – rape, murder, torture, etc are really (that is, objectively) wrong; (3) Therefore there is a God. This argument depends on morality being objectively true, which many now dispute. It also has to show why or how God is the grounds for morality. Further, it depends on there being no other viable grounds for moral objectivity. The role could be fulfilled by Platonic idealism instead, for example – which is the idea of the independent existence of moral concepts. But Platonic idealism has many problems of its own.

• The Cosmological Argument

This argument relies on the idea that an adequate explanation for something that does not have to exist – such as the universe – relies on something with causal powers that exists necessarily – that is, on God. The ‘Kalam’ version of this argument goes like this: (1) Everything that comes into existence has a cause; (2) The universe came into existence; (3) Therefore the universe has a cause; (4) To avoid an infinite regress, this cause must be a necessarily existent being; (5) That cause must be God; (6) So God exists. The main problem with any cosmological argument is demonstrating why God is a necessarily existent being. whereas the universe is only contingent – that is, not necessary.

• The Ontological Argument

This argument revolves around the idea that God must exist simply because of the type of being he is. Anselm’s version goes something like this: (1) God is defined as ‘The greatest of all possible beings’; (2) It is greater to exist than to not exist; (3) A greatest of all possible beings that exists is therefore greater than one that doesn’t; (4) Therefore God exists. Ontological aguments rely on the dubious-looking idea that the definition of God itself proves he exists. However, it’s difficult to pin down exactly what’s wrong with this approach, if anything.

G.B.