Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Alien: Covenant

Stefan Bolea talks of madness, antihumanism, and the arrival of the new gods.

“And just as paganism was to give way before Christianity, so this last God will have to yield to some new belief. Stripped of aggression, He no longer constitutes an obstacle to the outburst of other gods; they need only arrive – and perhaps they will arrive.”

(E.M. Cioran, The New Gods, 1974).

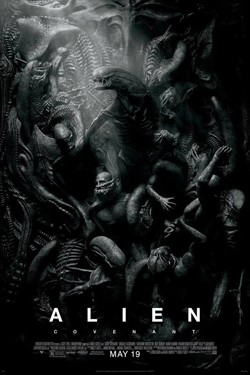

Ridley Scott’s 2017 film Alien: Covenant is the second Alien prequel and the sixth title overall from the Alien series. It’s a sequel to Prometheus (2012), a production praised for its stunning visual quality. Alien: Covenant contains references to poetry from Milton to Shelley; to classical music (Wagner); to the history of religions (especially Gnosticism); and to psychology (both Freud and Jung). But most of all, Alien: Covenant can be understood as a meditation upon the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche and Emil Cioran’s antihumanism.

After a prologue, the movie follows the journey of the starship Covenant, which is carrying 2,000 comatose colonists to the planet Origae 6. It is set in 2104, eleven years after the events in Prometheus. The ship is damaged in an accident, and the android Walter (Michael Fassbender) wakes the crew. The captain has burned to death in his stasis pod, leaving Oram (Billy Crudup) in charge. The death of the original captain sets the tone for a state of anxiety, hesitation, and disorder, and Oram has difficulty asserting his authority.

The android David has the whole world in his hands.

Against the recommendation of the original captain’s widow (played by Katherine Waterton), the new captain decides to investigate a radio signal picked up from a nearby planet. Oram leads the exploration of this Earth-like planet, which contains vegetation but seems devoid of animal life. Two members of the crew are infected by alien spores and later killed by the creatures that burst from their bodies, and things rapidly go downhill. At this tricky juncture, up pops David (Michael Fassbender again), an android who was one of the central characters of Prometheus, and who has been stranded on the planet since the events of that film. He scares the aliens away and leads the crew to the temple of a nearby ruined city. From now on the story takes an interesting philosophical turn and I won’t rehearse the plot details, preferring to draw on the film’s philosophical themes.

Rebellion & Madness In Space

The android David is the main character of the movie. His role might be compared to that of Milton’s Lucifer or Mary Shelley’s unnamed monster in Frankenstein. David’s rebellious nature is obvious in the preface during an opening conversation with his creator, trillionaire Peter Weyland (Guy Pearce), when he says, “You seek your creator; I am looking at mine. I will serve you, yet you are human. You will die, I will not.” This echoes the famous role reversal in Frankenstein where the monster says, “You are my creator, but I am your master; – obey!” It reminds me also of Hegel’s dialectical shift in The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), where the slave becomes the master of the master.

The mortality of his ‘father’ is the crux of David’s defiance. Without death, there would be no anxiety: one might say that all forms of fear sing a hymn to death. Without this anxiety, our relationship towards the divine (the Father of fathers, the King of kings) would be transformed. We would no longer feel inclined to play the ‘comedy of obedience’ because our fears of the unknown as well our hopes of reward would be greatly diminished.

David is Walter’s doppelgänger: they are different generations of the same make of android. While David is more creative and has a propensity towards disobedience, Walter has been upgraded to provide more reliability and fidelity. This adjustment in creation resembles the genesis of angels compared with that of humans. Although the angels were clearly superior beings, they were inclined to rebel against their Creator and provoke a state of what the Romanian philosopher Lucian Blaga has called ‘theo-anarchy’, a kind of divine disorder. The humans by contrast are like the next generation androids – more inclined to serve and worship after being equipped with the virus of anxiety and the biological duty to die.

In a Jungian sense, David is Walter’s shadow, a version of the archetype of the enemy, the evil stranger, or the devil. In this context we can discuss psychosis. David wrongly attributes the poem Ozymandias to Byron (it’s one of Shelley’s), and Walter comments: “When a note is off, it eventually destroys the whole symphony.” Walter is here using Arthur Schopenhauer’s definition of insanity, understood as a disturbance of memory. The Romanian Schopenhauerian poet Mihai Eminescu (who himself eventually died in a mental institution) also uses musical imagery to speak of insanity: “All the lyre’s chords are broken, and the minstrel man is mad.” Moreover, the musical metaphor of madness is a direct reference to Wagner’s prelude ‘Entry of Gods into Valhalla’ from Das Rheingold (1854) – which is played at the beginning and the end of Covenant (proving that this interpretation has managed to capture at least some of the intentions of the creators of the movie). Wotan, the ruler of the gods, is seen by Jung as a darker version of Dionysus, Nietzsche’s archetype of chaos. Jung wrote, “Wotan is the noise in the wood, the rushing waters, the one who causes natural catastrophes, and wars among human beings.” The Swiss psychiatrist also claimed that Nietzsche has had a ‘Wotan experience’ that foreshadowed his descent into madness.

Alien: Covenant images © 20th Century Fox 2017

Alien Antihumanism

The most important theme of the movie is the problem of antihumanism, a concept I use in a slightly different sense than Michel Foucault’s. The French philosopher spoke of the death of a certain concept of humanity following the demise of God: “Man would be erased like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.” However, poets such as Baudelaire and Lautréamont and philosophers such as Stirner, Nietzsche and Cioran add misanthropy – dislike of mankind – to their antihumanistic project. While Foucault alluded to the downfall of man understood in a certain type of way, and to the arrival of a non-humanistic system of reference, some post-Romantic poets and philosophers see themselves as agents of destruction – of what Nietzsche called ‘active nihilism’ – and would like to finish with the saga of humanism altogether through a Schopenhauerian process of universal death. Moreover, Nietzsche spoke of the Übermensch [‘overman’ or ‘superman’] as an overcoming of the traditional man, a sort of transgression of normal humanity, and Cioran referred to the not-man – a psychological mutation of the species, a being who is human only from a biological perspective. The Übermensch and the not-man can both be seen as possible paths for humanity’s evolution. They are also a metaphor for the current impasse of humanism: the feeling that the human species is in a certain biological sense dying, and that biotechnological enhancement in the near future will transform humanity to the core.

Cioran’s not-man might be a subtler and more complicated idea than the Übermensch. They are both ‘beings of overcoming’; but if Nietzsche’s concept has an upwards and somewhat utopian quality, Cioran’s notion raises the pessimistic possibility of a more dystopian transgression of humanity. The not-man is the infernal abyss of the Übermensch: the not-man ceases to be human – “I was man and I no longer am now,” observes Cioran – but cannot aspire to the heroic status of the Übermensch. The not-man is a sort of shadow of the ideal, a Platonic form relegated to the underworld. The not-man could fail even worse than the human being because its status is more intricate and ambiguous: “I am no longer human… What will I become?”

The key scene from Alien: Covenant takes place after a neomorph (a species of alien) severs the head of one of the Covenant’s crew. David surprises the neomorph feeding, then starts looking at its face (it doesn’t have eyes) with awe and pity. This scene is significant because it’s two different kinds of not-men looking at each other: it’s a meeting between non-human and non-human unmediated by human intervention. David’s gaze into the abyss of an even more radical inhumanity – into the shadow of his shadow – revives Baudelaire’s ‘looking-glass of the shrew’, the mirror of unidentification where a schizophrenic sees something other than himself. “But am I not a false accord / Within the holy symphony?” asks Baudelaire, again echoing the musical imagery of madness.

Android Devil, Or God

Eventually Oram breaks the spell and shoots the neomorph. In the same scene, Oram speaks of the devil: “David, I met the devil when I was a child. And I’ve never forgotten him.” This alludes to Nietzsche’s assertion that the so-called ‘higher men’ would see the Übermensch as a devil. An important issue connected with antihumanism is ‘creationism’, in the sense of ‘having an appetite for creation’. The devil is traditionally seen as a decreator. In the Garden of Eden he hijacks God’s influence by inspiring disobedience in Adam and Eve. Yet we see in David a devil who aspires to overcome his condition, who wants to create as God creates, when he saves an alien embryo so that the aliens can be recreated. More precisely, David is one of Cioran’s new gods. Just as Christianity demonized the gods of antiquity, the new gods will vilify the Christian God. This demonization would be accomplished with the death of the idea of resurrection, so that mortality defeated even Jesus: “Christ will not harrow Hell again: He has been put back in the tomb, and this time he will stay there,” notes Cioran. One could say that humans believe they believe in God, but truly believe only in death.

The android who has overcome the profound anxiety of death is a created creator who aspires to the divinity of his creators’ Creator. David’s appetite for creation thus transforms him into an equal of Goethe’s Prometheus:

“Here sit I, forming mortals

After my image; a race, resembling me,

To suffer, to weep,

To enjoy, to be glad,

And thee to scorn,

As I!”

© Dr Stefan Bolea 2018

Stefan Bolea earned PhDs in both Philosophy and Literature from the University of Cluj-Napoca, Romania. He is the editor-in-chief of the online magazine Egophobia: egophobia.ro.