Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Philosophical Haiku

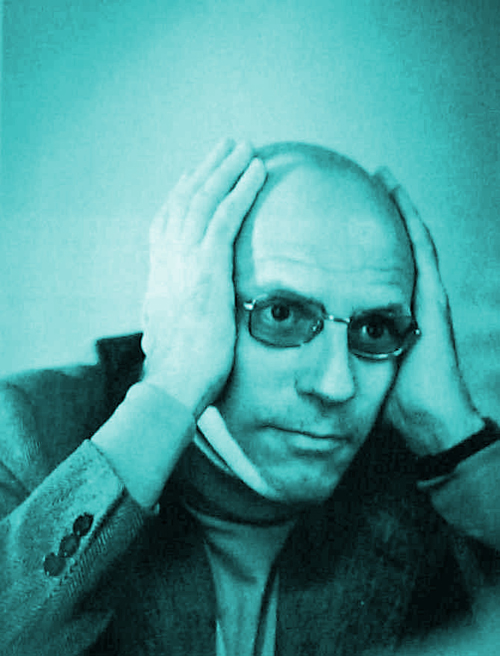

Michel Foucault (1926-1984)

by Terence Green

Dig into the past

Reason, madness, punishment

Knowledge disinterred

As a boy, the French philosopher Michel Foucault had a flair for Greek, Latin and history. As a young man, he had a flair for the macabre: his bedroom at his boarding school was adorned with images of torture and war, and he reportedly once chased a fellow student with a knife. For some reason, he had few friends.

When he wasn’t contemplating violence and death (including his own), Foucault was usually found reading works by Hegel, Marx, Kant, Husserl, and Heidegger. One of the unfortunate outcomes of being influenced by such generally obtuse writers was his own tendency to write in a way that obscured his ideas. This has led some detractors to suggest that his works are pretentious waffle.

Perusing obscure manuscripts from the past, Foucault hoped to shed light on the present. He was, he said, like an archaeologist sifting through the broken shards of bygone ages with a view to helping us understand ourselves. His primary concern was with unearthing the foundational knowledge of customs, theories, and institutions which marked out one epoch from another. Looking at the history of what he called the ‘discourses’ of such practices as biology, politics, and medicine, he asked how a particular discourse emerges, how it changes, and how it structures the way we see the world. In particular, Foucault believed that science and the discourse of reason were a way for the establishment to wield power – by constructing categories we can label people, and then treat them accordingly. For instance, homosexuality was for a long time categorised as a form of illness, and those ‘diagnosed’ with it could then be subjected to all sorts of ‘cures’. Similarly, Foucault argued that ‘madness’ is only a social construct used as a form of control: if you were deemed ‘mad’, then certain treatments awaited you (and they weren’t going to be fun). These interests in turn led to his inquiries into the nature of punishment, particularly in schools and prisons. Punishment is, after all, the manifestation of power par excellence.

For what it’s worth, in my view, you don’t have to be mad to read Foucault, but it helps.

© Terence Green 2018

Terence is a writer, historian, and lecturer, and lives with his wife and their dog in Paekakariki, NZ. hardlysurprised.blogspot.co.nz