Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Philosophy of Work

Alessandro Colarossi has insights for the bored and understimulated.

If you’ve ever found yourself staring blankly at a spreadsheet or nursing a lukewarm cup of coffee while daydreaming about your next vacation, this is for you. Yes, you, the one who periodically contemplates existential questions between email exchanges and Zoom meetings. If your work feels like a necessary yet uninspiring pursuit, a means to fund your ‘real life’ outside the office, let us delve together into the philosophical underpinnings of work. Who knows, we might find ways to render the banal a little more bearable, or even meaningful.

Aristotle and the Dignity of Work

Aristotle, one of the most influential philosophers in Western thought, had distinctive views on work. He made a clear distinction between chrematistics (wealth acquisition) and oikonomia (household management). In his view, work performed purely for the sake of livelihood, or chrematistics, was not inherently virtuous; it was simply a means to an end. However, work that contributed to the well-being of the community, or oikonomia, was considered virtuous as it served a higher purpose.

Aristotle asserted that work aimed at wealth accumulation (chrematistics) was a practical necessity of life, but not a noble goal. It was essential to fulfill our basic needs such as food, shelter, and clothing. However, when wealth accumulation became the primary aim, it could lead to an unhealthy focus on materialism, potentially degrading societal values and causing imbalance in life.

On the other hand, Aristotle regarded oikonomia as a more virtuous form of work. This was work that concerned the well-being and self-sufficiency of the household and, by extension, the community. It involved efficiently managing resources, caring for people’s needs, and contributing to the collective health and prosperity. Oikonomia was inherently selfless and community-oriented, encouraging cooperation and sharing.

Beyond mere wealth acquisition, Aristotle believed that work should also be about fulfilling one’s potential and living a good life, or eudaimonia. He argued that each person had a unique set of skills and virtues (arete) that could be cultivated through their work. By finding work that allowed them to express and develop these virtues, individuals could contribute to society while also achieving personal fulfillment and happiness.

To illustrate this, let’s consider the role of a computer repair specialist working a 9-5 job in the contemporary context of 2024. If she approaches her work from the perspective of chrematistics, she sees her job as merely a way to earn money. She is focused on completing as many repairs as possible each day to maximize her income. The quality of her work and its impact on her clients’ lives are secondary considerations.

If, however, the same computer repair specialist chooses to adopt the principles of oikonomia, her approach to her work shifts significantly. She understands that her job plays a crucial role in enhancing the digital life of her community, helping people stay connected and productive in an increasingly digital world. She takes the time to understand her clients’ needs, ensures that her repairs are effective and durable, and offers advice on how to maintain devices and protect data.

She might even use her skills for broader community benefits, such as offering reduced-rate services to schools or charities or running workshops on computer literacy. By doing so, she contributes to the overall well-being of her community, helping individuals and businesses avoid costly downtimes, protect valuable data, and leverage technology more effectively. Her work gives her not only a paycheck but also a sense of fulfillment, knowing that she is making a difference.

Aristotle’s philosophy invites us to rethink the purpose and meaning of our work. It encourages us to view our work as a means to contribute to society and fulfill our own potential, rather than seeing it simply as a source of income. These principles have profound implications in today’s world, where work and wealth accumulation are often seen as primary measures of success. (see Aristotle, Politics)

Karl Marx and Alienated Labour

In the 19th century, Karl Marx radically transformed the philosophical discourse on work. His concept of ‘alienation’ became central to understanding the worker’s relationship with his or her labor in industrial societies. Marx argued that under capitalism, workers are estranged from their productive activity, the products of their labor, their fellow workers, and their potential for self-realization (Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844). For Marx, true human fulfillment lies in unalienated labor where workers can freely express their creative potential.

In Marx’s understanding, the capitalist system can foster ‘alienation’ where workers, like our computer repair specialist, might feel a disconnection from their labor, its products, their fellow workers, and their own potential. They become mere wage slaves.

If this repair specialist operates within the traditional capitalist model, she may experience Marx’s ‘alienation’ in several ways. Her work could become a series of repetitive tasks aimed solely at maximizing productivity and profit, disconnecting her from the more intellectual and creative aspects of her labor. She would be doing the work, but control over how it is done may lie with her employers or the demands of the market.

Marx’s concept of alienation encompasses various dimensions that directly relate to our specialist’s situation. First and foremost, Marx discussed the alienation from the products of labor. In the case of our specialist, the computers she fixes do not belong to her but to her clients. The profit derived from her repair work primarily benefits not her but the business owners. Despite playing a crucial role in generating this wealth, she only receives a fraction of it, leading to a sense of estrangement from the outcomes of her own labor.

In addition to this, Marx also highlighted how capitalism can result in workers being alienated from their fellow workers. Our repair specialist might find herself in an environment where competition is the norm, hindering the development of strong cooperative bonds with her peers. Her work could become a solitary endeavor, lacking meaningful human interaction, thereby increasing her sense of isolation.

Furthermore, the specialist may face alienation from her own potential for self-realization. Capitalist workplaces often restrict opportunities for individual growth and creativity in the pursuit of increased productivity and profit. The specialist might be discouraged from innovating, learning new skills, or taking on more complex and rewarding tasks. Such limitations may impede her self-development, further deepening her sense of alienation.

For Marx, the antidote to alienation lies in the creation of a society where workers have control over their labor, can express their creativity, collaborate with their peers, and connect with the products of their work. For our computer repair specialist, this could mean restructuring her work environment to encourage innovation, learning, and cooperation, while also ensuring that she benefits more directly from the value her work creates. Such a transformation would align with Marx’s vision of unalienated labor, where work becomes a means of personal fulfillment and creative expression (Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844).

Schopenhauer and the Pursuit of Goals

A fundamental element in Arthur Schopenhauer’s metaphysics is the ‘will to live’. He argues that humans are continually driven by a blind urge to strive towards existence and life. We have no final purpose. Therefore we struggle towards achieving goals, but once a goal is achieved, the satisfaction is only temporary, for a new goal or desire arises. This ceaseless striving can create a cycle of anticipation and dissatisfaction, which characterizes much of human life, and which is the root of suffering.

Schopenhauer’s perspective here can be applied to the realm of work, shedding light on the dynamics that shape our working lives. Like the ceaseless striving described by Schopenhauer, the computer specialist’s professional journey is marked by a continuous pursuit of goals. Each task completed and computer repaired may bring a momentary sense of accomplishment, but it is swiftly followed by the emergence of new challenges or demands.

In this context, the specialist’s experience aligns with Schopenhauer’s observation that the fulfillment of one goal only gives rise to the next desire. The completion of a repair task may offer a brief respite, but soon enough new issues to address or improvements to make arise, reigniting the cycle of anticipation and dissatisfaction.

This provides a philosophical framework to understand the inherent restlessness and perpetual striving that characterises many jobs. By recognizing the parallels between Schopenhauer’s metaphysics and the computer specialist’s experience, we gain more general insights into the fundamental nature of human existence and the ongoing pursuit of goals that shape our lives. (Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, Book 2)

Perspectives from Eastern Philosophy

Eastern philosophical traditions also offer valuable insights into the nature of work. In the Bhagavad Gita, a central text of Hindu philosophy, work is seen as a duty that must be performed without attachment to its fruits or outcomes, a principle known as Karma Yoga. This approach encourages individuals to focus on the act of working itself, rather than the rewards it may bring.

Applying the principle of Karma Yoga to our computer specialist’s situation suggests that she should approach her work with a sense of detachment from the results. Instead of fixating on the potential benefits or gains she may derive from her repair work, she can find fulfillment by wholeheartedly engaging in the process itself. By immersing herself in the present moment and dedicating her efforts to the task at hand, she can cultivate a sense of both purpose and contentment, independent of external outcomes.

Buddhist philosophy, on the other hand, emphasizes the idea of ‘Right Livelihood’ as part of the Eightfold Path. It posits that one’s work should not harm others and should be an expression of compassion and wisdom. This perspective invites a reflection on the ethical dimensions of work.

From this Buddhist perspective, the specialist should reflect on the impact of her computer repair work on others and strive to ensure that her endeavors do not cause harm. By approaching her profession with mindfulness, empathy, and a commitment to ethical conduct, she can infuse her work with a deeper sense of meaning and contribute to the well-being of those she serves.

By integrating these Eastern philosophical perspectives into our analysis, we expand our understanding of work beyond its instrumental and material dimensions. We recognize the value of cultivating a mindset that transcends attachment to outcomes, emphasizing the intrinsic worth of the work itself. Moreover, we acknowledge the ethical implications of our professional pursuits and the potential for work to be a vehicle for compassion and wisdom.

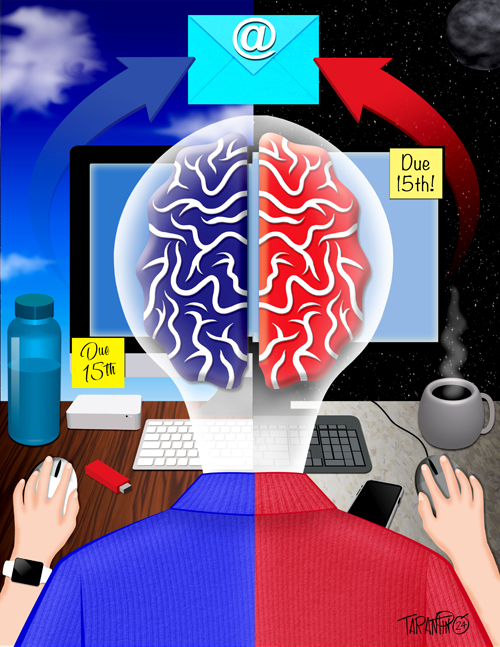

Image © Steve Tarantino 2024. Please visit stevetarantino.com

Postmodern Perspectives on Work

Postmodern philosophers, such as Michel Foucault and Jean Baudrillard, offer valuable insights into the complex dynamics of power, knowledge, and work. Foucault’s concept of ‘biopower’ delves into how modern societies exercise control and regulation over their populations through various mechanisms, including work. According to Foucault, work serves as a means of exerting power, as it enables the control and disciplining of bodies, forming habits of obedience that ultimately shape individuals into ‘docile’ subjects (Foucault, Discipline and Punish).

Jean Baudrillard’s analysis of consumer culture emphasizes the transformation of work and production in post-industrial societies. Baudrillard argues that in these societies, work and production have become simulacra, detached from their original purpose of satisfying human needs. The nature and purpose of work become increasingly enigmatic and elusive as they are subsumed by the hyperreal nature of consumer culture (Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation).

Baudrillard’s analysis further illuminates the postmodern landscape, wherein work and production have become ensnared within a hyperreal domain, characterized by an over-abundance of signs and symbols. The enigmatic nature of work in the realm of consumer culture intensifies feelings of disorientation and blurs the boundaries between reality and illusion.

To Those Who Tolerate Tedium for the Paycheque

Our exploration of philosophical perspectives on work reveals that this central aspect of human life is a rich and complex tapestry, woven with threads of necessity, desire, alienation, fulfillment, power, and ethics. Work is not merely a means to an end – a way to earn the wage that allows you to enjoy life outside the confines of your office. Rather, it’s a profound human activity that reflects our deepest desires and highest aspirations. As we navigate the mundanity and monotony of our daily tasks, let’s remember that even in the driest desert of tedium, an oasis of meaning might be found.

© Alessandro Colarossi 2024

Alessandro Colarossi is a Technical Consultant from Toronto. He has a BA in Philosophy from York University, and an Advanced Diploma in Systems Analysis from Sheridan College, Toronto.