Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Interview

Robert Stern

Robert Stern talks with AmirAli Maleki about philosophy in general, and Kant and Hegel in particular.

Robert Stern FBA (1962-2024) was a British philosopher who served as a professor of philosophy at the University of Sheffield. He sadly passed away from brain cancer on 21 August 2024 at the age of 62. We publish this interview as a tribute to his work, especially in the field of German philosophy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Professor Stern, in your opinion, what is the need to study the philosophy of German idealism in the modern world? Can this philosophy have a lesson for us?

Perhaps we first have to be clear what is meant by German Idealism here. In particular, is Kant included as a ‘German Idealist’, or do we mean primarily Fichte, Schelling and Hegel? [‘Idealism’ is the idea that the only things that ultimately exist are minds and their experiences, Ed.] If Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) is included, I imagine no philosopher would seriously question the significance of German Idealism for the modern world, given Kant’s continued influence, which is clear even today, particularly perhaps in ethics, even if there are few transcendental idealists still around [Kant’s version of idealism, Ed]. But it might be thought that the place of the others is less obviously secure as compared to their heyday, when for example GWF Hegel (1770-1831) was the leading philosopher in Germany, or when the British Idealists took Hegel up at the turn of the nineteenth century into the twentieth, or when he was central to debates in critical theory in the 1950s and 60s, and so on. However, there is little doubt that interest in Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel is again on a rise, at least as measured by philosophical activities such as conferences and publications, as well as the numbers of lecturers and graduate students interested in their work. When I worked on my PhD in the 1980s it was a rather isolated interest. Now it’s much more popular and central.

So what explains the change? I think there are many explanations from within philosophy. One is that the confidence in pure analytic philosophy began to come under question, leading to a greater diversity in views and an interest in other ways of doing philosophy, which Hegel, amongst others, came to represent. As a result, figures such as Charles Taylor, Richard Rorty, Alasdair MacIntyre, John McDowell, and Robert Brandom brought Hegel into their discussions. That Hegel had been ignored began to be seen as a potential mistake. Thus whereas previously he seemed surpassed and irrelevant, this is now no longer assumed. And the rise of interest in Hegel has led to corresponding interest in his friends Fichte and Schelling, as providing related but different models of how to take the idealist tradition forward. In this way, I think German Idealism has indeed come back to offering some significant alternative views in the contemporary philosophical world. But you may also be interested in this tradition’s possible relevance to the contemporary world more broadly. In my view, the broader importance of Hegel’s thought lies in its attempt to reconcile a variety of apparent conflicts – for example, between the collective state and the freedom of the individual, or between religion and science. I would suggest significant lessons can be discovered at this level, too.

After all the time you’ve worked on German Idealism, what do you think is the right way to study this historical period?

Assuming we’re not including Kant in the German Idealism group as such, then bringing him in is of obvious significance, as he is clearly the most significant figure of that time, both in terms of setting out various problems in a distinctive way – concerning a priori knowledge, free will, and the relation between philosophy and religion, for example – as well as suggesting options – such as transcendental idealism, and the limitations on theoretical knowledge. Kant is also the reason I initially came across German Idealism, since I started to read Hegel because of his criticisms of Kant. However, once Kant’s in place, there is then a wider background to be read: philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, and Spinoza, and also theologians like Martin Luther, and broader thinkers and writers such as Goethe, Hölderlin, and Schiller. There is also a need to understand the wider historical context, such as issues related to politics, art, and religion: for example the impact of the French Revolution on German thinking at the time. Obviously this is rather a lot to take on in one go, but it will doubtless be the way in which an inquiry into some narrower aspect is likely to develop over time.

In my opinion, philosophy is an ever-growing entity that cannot be limited to a specific nation. Some thinkers, though, believe that philosophy in Germany is the perfection of thought. Do you think this is correct?

I certainly agree with you that philosophy as such should not be limited to German Idealism; and likewise I would not treat this period of philosophy as the ‘perfection of thought’. Instead, I think that, rather than having brought philosophizing to its end, like any significant philosophical position it remains in dialogue with other philosophies. I don’t think this is because each country has its own separate tradition, and so is limited in that way. Doubtless factors such as language, politics, history, and so on have some influence, and so make this ‘geographical’ language meaningful – as in the terminology of ‘German Idealism’, ‘American Pragmatism’, or ‘British Empiricism’, for example. But I don’t think this limits these traditions to one country. Each of them has had an impact in many other national traditions, too.

After reading your book Kantian Ethics: Value, Agency, and Obligation (2015), a question arose for me: What would be Kant’s moral goal for today? Also, did Kant have a theological approach in his ethics, and if so, how should we interpret that today?

Those are very large questions! Starting with your first query, perhaps one way to address this is to use the now-common triadic distinction between meta-ethics – namely, the nature of moral knowledge – normative ethics – which treats various actions as right and wrong, and hence asks which broad ethical approach is the one to follow – and applied ethics – which asks, how should various specific ethical issues in our lives be resolved? Next, I would assume that just as he did in his lifetime, Kant today would still aim to resolve all these levels in his distinctive way, and respond to various objections that have been made against his ideas – such as his famous claim about lying being ruled out in all circumstances, and his claims about the centrality of duty over other motives. Overall, and coming round to your second question, there is also the issue of how far Kant’s clear defence of ethics even against commonsense views of causation depends on religious assumptions, or instead manages to incorporate religion within ethical thinking, so that ethics is prior to religion. This issue is certainly raised by his book Religion Within the Boundaries of Mere Reason (1793). On balance, I would take the last view. Then a more secular option may seem persuasive – as is believed by most contemporary Kantians – though the place of religion still remains a question that hangs over his ethical position.

You addressed Hegel’s thinking in another work, Hegelian Metaphysics(2009). Do you think metaphysics isn’t over for the modern world? In my opinion, metaphysics is a mere verbal interpretation by people, and everything eventually returns to physics. What do you think?

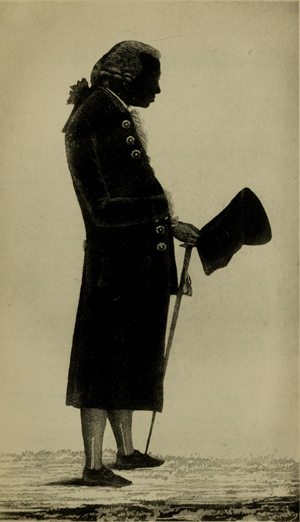

Kant in outline

I’m afraid my view of metaphysics is a bit more positive and ambitious than yours, though it may well appear naïve! Of course, Hegel was fully aware of the limitations on metaphysics suggested by Kant [who argued that we don’t directly experience reality itself, only a representation of reality], and the problems Kant raised for the kind of knowledge that metaphysics seems to involve, which then becomes one of the key arguments for his transcendental idealism. I take it that your comment that ‘metaphysics is a mere verbal interpretation’ is meant in this broadly Kantian direction, since we can say that for Kant metaphysics tells us about the limits of human thinking rather than about reality or being itself. However, I think that ultimately, Hegel holds that this kind of modest-looking conception of metaphysics is in the end unwarranted. On the one hand, it is not clear that identifying the limits of human thought is any easier than identifying the limits of being. On the other hand, it is not clear why certain Hegelian claims about those latter limits are implausible – like the claim that pure being is a form of nothingness that must take a more structured form instead, which is initially characterized as determinate being, but which has its own metaphysical problems. And so the Hegelian dialectic goes on…

In relation to your thought that metaphysics must ‘return’ to physics, I’m not sure that this can be the case, since, while physics focuses on the way the world is at an empirical level, by contrast metaphysics attempts to understand how it must be in a more than empirical sense – so the interests of the two seem to differ significantly. A Kantian might then try to limit metaphysical claims to how reality must appear to us rather than how it actually must be. But I think Hegel suggests that this modesty is false, as only some misleading Cartesianism could make it seem that claims about the nature of the appearance are easier to establish than claims about the nature of reality. In my view, this is in the end what makes Hegel’s Science of Logic (1812) a metaphysical text rather than a transcendental one – in the Kantian sense of ‘transcendental’.

What do you think is Hegel’s research method? Can he be useful today, or is his work finished, leaving no lasting message? Also, many consider Hegel’s language difficult: what do you think is the right way to study him given this?

I will try to answer your questions in turn. One fundamental feature of Hegel’s method, I would say, is his approach of so-called ‘immanent critique’: rather than dogmatically assuming that some view is correct, his approach is to consider alternative views and show when in their own terms they become self-undermining. So for example, on some views of action, actions become treated as deterministic in a way that makes it incoherent to talk of them as ‘actions’ [ie, voluntary movements] at all, so further developments are required. This all then relates to Hegel’s claims about his method being dialectical, meaning that a limited idea can turn into its opposite, so that some way of moving beyond the contradiction needs to be found. Or, to use our example, it means that our view of action and its causes must become more sophisticated.

On your second question, I would suggest that one way Hegel remains relevant for today is that his own attempts to get beyond these various dichotomies – such as freedom and determinism, individual and state, substances and properties, and so on – still offer us a valuable approach to a variety of philosophical issues. Even if we reject his answers, the goal of getting beyond these dichotomies remains an attractive one, it seems to me.

Finally, on the issue of Hegel’s language, I have perhaps a rather eccentric view, which is that Hegel’s language is not much more difficult than that of many other philosophers, such as Aristotle, Spinoza, or Kant – it’s just that we’re more used to reading those others, so we find them easier. Of course, one might then object about philosophy more generally that it is too obscure and demanding, and should be communicated more simply. But here Hegel’s answer would be that philosophy offers a way of thinking which more ordinary thinking finds difficult, as philosophy operates with subtle distinctions – for example between freedom on the one hand, and obeying a law on the other – so that to set out the more philosophical view will always appear hard compared to how things seem to us initially, but that we must learn to get beyond this if we can. Nonetheless, if we comprehend his dialectical approach, we may be less dismissive of his apparently difficult language by seeing that the reasons for the difficulty are not an ineptitude in communication, but instead reflect the deep ambitions of his project, in which such difficulties seem inevitable, and for which he can therefore be forgiven.

Do you think German idealism in particular and philosophy in general are temporary knowledge and don’t have a message for the future? If they have a message, what’s the correct way of studying philosophy without bias?

That’s an interesting question, and it perhaps needs a complex answer. On the one hand, it is certainly true that some of the key ideas and concerns of historical philosophers can seem to date – for example, concerning assumptions about the natural world, or about gender or race. But on the other hand, despite the historical distance, the most significant philosophers still speak to us: though which philosophers these are can change, as some fall into obscurity – as Hegel did the 1930s, for example – and others become prominent, while others are rediscovered. I therefore think it would be too naïve to assume that since German Idealism rose originally around two centuries ago, then it must not relate to us today. It is true that some issues that concerned them then are different from our concerns, and vice versa – but even distinctively modern concerns like climate change and threats to the environment might learn from Schelling’s distinctive attitude to nature, for example. That does not mean we should aim to distort their views, as then we will not learn anything from them; but nor do we necessarily have to read them as confined to their time and as cut off from ours, as that distinction seems too crude.

What can we expect from philosophy for the future? What should it do?

I imagine that two areas will be of increasing interest because of their wide significance – namely, climate change and AI. Philosophy is already engaging with both issues. Gender issues may well also remain central, though one might hope that some way to settle this debate can be found, or at least a way to reduce some of the heat surrounding it. To the extent that more traditional philosophical issues relate to the fundamentals of the human condition, I would think they’ll remain central, and I doubt that they will be resolved once and for all. However, that’s arguably philosophy’s great strength rather than its weakness – a testimony to its centrality in our lives. This does not mean that new options will not arise, in just the way that has often been fruitful in the past. Nonetheless, any grandiose claims that new options can settle things once and for all – as was claimed for logical positivism, or pragmatism, or even German Idealism – are probably premature, and doomed to failure.

What message do you have for young researchers in philosophy, especially in the philosophy of German Idealism?

I think this is an exciting time for philosophy, and especially for German Idealism, where there is now a lot of interesting activity. As I mentioned, this is very different from how things were when I began in the 1980s. At that time, while Hegel still retained something of his position in German thought, he was largely ignored in the Anglo-American world. But today he is a much more significant figure, both for historians of philosophy such as Pippin and Pinkard, but also for those developing various contemporary lines of thought, such as McDowell and Brandom. I would hope that this would encourage young researchers to take these developments further. The German Idealist tradition is also becoming handled in a more sophisticated way than it has been in the English-speaking world, such as in work by Peter Dews on Schelling, and Daniel Breazeale on Fichte. I would expect this to be developed further in the future. At the same time, many fundamental issues are still under debate, such as the nature of Hegel’s idealism, or the significance of Schelling’s critique of him. So it remains an area of interest that I believe researchers may find highly significant for many years to come.

AmirAli Maleki is a philosophy researcher and the Editor of PraxisPublication.com. He works in the fields of political philosophy, Islamic philosophy, and hermeneutics.