Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Political Philosophy

Success & Luck

Carlo Filice argues that we should share our success, even if it’s hard earned, because we often don’t deserve it as much as we’d like to think.

In thinking about slightly redistributive economic policies, it is essential to address a belief many people hold deeply. This is the belief that honest, hard-working people always deserve most or all that they earn. This belief is bound up with notions of fairness, of self-ownership, and with ideas of the very essence of what a person is. Unfortunately these are also the very notions that undermine the belief in absolute deserving, once examined.

Let’s start with the part that’s hard to dispute. Those who end up toiling hard in low paid physical or mental labor deserve their pay, and much more. At the opposite end are those who end up fabulously wealthy who have often been targeted as undeserving of their sheer amounts of money. A case in their defense could be made if their success was attained fairly and was a necessary by-product of the best possible market system – meaning the one that benefits people more than any of the alternatives. But neither of these conditions are empirically true.

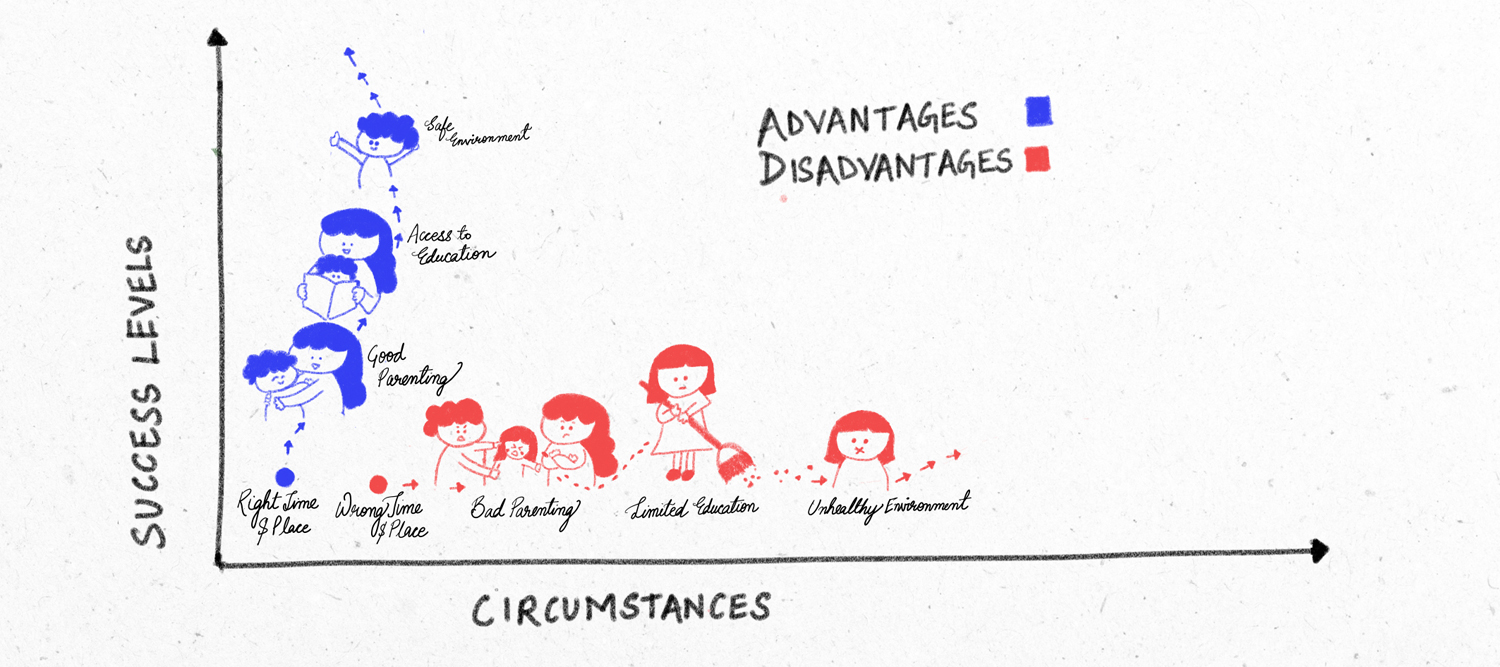

First, most current market systems do not benefit all people, or even a greater percentage of people, more than all alternative systems. Scandinavian countries often do best on overall happiness, and they operate extensive welfare systems. Second, the neo-liberal free market system is not like Monopoly, where chance and skill combine to produce winners fairly because all the players start out with equal resources. Rather, the starting points are always deeply unequal. Not surprisingly, most children of upper class families remain in the upper classes as adults, and most children of lower class families remain in the lower classes. This is so even if there is no formal cheating by the upper class parents and children. The sociological data supporting this seems incontrovertible.

Note that the second point applies not just to the fabulously rich, but also to many of us who are comfortably well-off. It applies to the wide spectrum of skilled, honest people who end up highly rewarded: doctors, lawyers, engineers, investment consultants, professors, real estate investors, and so on. These are generally good folks who play an active role in creating their success. But it looks like members of this group in general do not deserve greater financial and status success than similarly hard-working people. Rather, such success was an accident of birth.

Beginner’s Luck

The reason why we may not fully deserve our success includes social starting-point inequality. It also includes other innate starting-point advantages that aren’t earned.

Take myself as an example. I am a tenured professor in an American college, and so I’m living a relatively charmed life. Yes, I worked my way to that position. But I also won in multiple aspects of the cosmic lottery. Successful middle-class individuals typically inherit good emotional and cultural springboards, such as devoted parents. We also tend to inherit genetic good fortune, ranging from health propensities to above-average cognitive potentials. We did not earn any of these factors. So we have been mostly lucky! We were born at the right time and place. We were not born in the midst of a vicious civil war, or in a permanent refugee camp, or in a gang-land ghetto or barrio, or in 800s Europe. Yes, we did work hard, and we made mostly smart choices. But hard work, determination, and decent choice-making are not exclusive to successful people. Many poor people, by the millions, if not billions, work hard and make decent choices, too. But their circumstances, both inner and outer, are more difficult. Their starting-points are unlucky, and being born in the wrong time and place is often decisive all by itself. In addition, genetic limitations and other disadvantages make things worse. These limitations range widely, from basic health impairments to severe insanity, and from bad parenting to poor schooling opportunities, to few work options. For many people hard work yields meager or even tragic results. And making decent choices is much easier when you’re healthy and well-fed. Try growing up in a crime-infested favela, or in a malaria-prone village.

Some of us do exemplify the much-eulogized success story. I was brought to the US as a boy by semi-literate parents. They were hard-working peasant farmers who became factory workers in the US. We did not speak English at home. But I was good in school: I did work hard, and I made smart choices. My stupid choices didn’t hurt too much. So do I now deserve the good fortune I have? Not for the most part, I think.

My starting points were crucial, even if in some ways humble. I was not born in 800s Europe. I had supportive parents. I had the aptitude and desire to learn. None of these factors were earned (barring reincarnation, which would be one way to achieve cosmic fairness, but which is outside the scope of this essay). I had access to publicly-funded schools and colleges in 1970s USA – access that I also did not earn. I was white, lived in safe neighborhoods, under a system of laws that provided background protections, at least in our area of northwest Chicago. Those conditions I also did not earn. So, while I did apply myself, all of my multiple fortunate starting points, both outer and inner, were unearned. The same can probably be said of most successful professionals across the globe, especially in richer countries. Fortune plays the dominant role in success.

The reverse is also true. Misfortunes in life’s starting points are very hard to overcome, all over the world. Children born in broken homes or dangerous neighborhoods face poorer prospects, and for them bad choices are often unforgiving. For example, your pollution-sickened parent sends you to the drug store at night; but you’re assaulted, and are scarred for life.

Yes, the gifts of good genes, cultural springboards, and right times and places, have to be complemented by good choices and hard work. Engaging your free will here is a factor for life success; but only a factor. Even in our inner sanctum of free agent contribution, luck plays a big role, since non-chosen genetic propensities affect our ability to freely contribute. Already at the very beginning of our lives we can be subject to attention deficit disorders, impulse control deficiencies, or worse impairments. We can be predisposed to various addictions. Alternatively, we can start off with all manner of talents and aptitudes. Especially pertinent are the capacities for what we call ‘self-discipline’ – crucial for any personal credit. These capacities are not distributed equally, even in healthy individuals. That means that self-discipline is naturally easier for some than others.

The upshot of all this is that we can only take partial credit even for our most intimate contribution to our success. It is true that initial talents and aptitudes need to be nurtured and developed. In this, an active part of me does play a role in addition to parenting, schooling, etc. But this active part needs a lot of good starting psychological material to work productively with. (Even this is an ‘at best scenario’, since many philosophers are skeptical of active aspects of ourselves, independent of character tendencies).

Luck & Legitimacy

Following a 1976 paper of the same name by Bernard Williams, in his 1979 paper ‘Moral Luck’, Thomas Nagel argued that even our moral score-card is partly a function of luck. For instance, it is easier to remain morally good if one happens to live in a sane and stable country, as opposed to growing up under a fascist regime.

Does our starting-point luck therefore mean that our honest accomplishments and wealth are illegitimate? No. They’re not like stolen goods or stolen titles. Honestly acquired success and wealth are legitimately ours. But all the same, this success cannot be said to be deserved, since it has mostly befallen us (I’m borrowing this distinction of ‘legitimate, but not deserved’ from the political philosopher John Rawls). We won the cosmic lottery. We won it by virtue of a ticket we did not steal: but neither did we buy the ticket. Genes, times, places, are our ticket, and our parents bought it for us. So, since we cannot say that we deserve our starting points, even our honestly earned wealth is mostly undeserved.

The comparison between life success and winning a lottery is, of course, only an approximation. Our contribution via hard work and smart choices matters. The free will element matters. We’re right to dig our heels on this point: not everything simply falls to us. Still, we are prone to self-congratulatory blindness, especially if we have achieved through effort. Therefore it is important to keep reminding ourselves that (1) Natural talent is not something one earns; and (2) Our developing of it, or not, depends mostly on social and character factors we also did not earn; and (3) Applying this talent productively requires a favorable social setting we also did not earn, as well as good fortune.

Implications

One upshot of these observations is that if 90% of our individual success is not down to our simply deserving it, then we should be more willing to share our success with those less fortunate, since their misfortune is also mostly undeserved.

How best to do this long-term is debatable. Rawls thought that a generous welfare state is called for. Scandinavian countries seem to have implemented this principle well. If this is the right model, should it be extended to a global welfare state? Maybe. But the issues are complex, and in any case we’re worlds away from that.

What if part of our initial lucky material inheritance is built from goods acquired illicitly by our ancestors? What if it was at least partly attained via violence, theft, or a systemically biased system? It may then be that those of us enjoying success built from this exploitation have an additional obligation to help those who start off as impoverished descendants of victims of that violence, thievery, and bias. Our obligation to share is then compounded. So perhaps some policy of reparations towards our aboriginal and slave-descendant siblings is appropriate. But what form this should take (how much, from whom, to whom, etc) is itself a complex issue, and itself needs to be carefully debated. But it’s a hopeful sign that public awareness is turning to this issue, after a long history of denial.

© Prof. Carlo Filice 2025

Carlo Filice is Professor of Philosophy at SUNY Geneseo, and author of The Purpose of Life: An Eastern Philosophical Vision (2011).