Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Can AI Teach Our Grandmothers To Suck Eggs?

Louis Tempany wonders whether the problem is with the machines or with us.

To put the title question into more straightforward words, will human life become so diminished that we will require machines to do everything for us? Will human life get to a stage where things we ought to know how to do – like egg-sucking, say – are being done by inanimate objects instead of us?

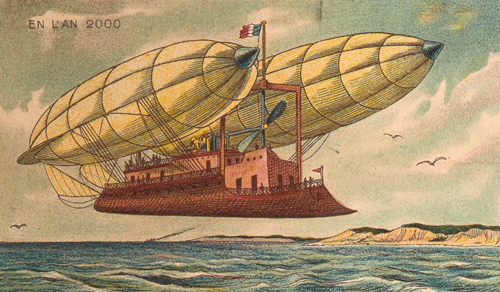

As far back as the nineteenth century scholars attempted to predict what technological progress we might make. Progress looks incredible in cartoonist William Heath Robinson’s satire on it – far brighter than reality. There’s plenty to marvel at: the mechanised steam mega-horse with smoking nostrils; the vacuum tube that transports you to Bengal; the mobile water dispenser… While some of these ideas may have come to fruition, most others are simply amusing and lack any kind of characteristics that modern machines possess. But even back then we feared that machines might someday overpower us. The In The Year 2000 images were commissioned from artist Jean-Marc Côté by a French toymaker for the 1900 Paris Exhibition, becoming famous when Isaac Asimov republished them eighty-six years later. Fritz Lang’s vision of the year 2000 in his silent film Metropolis, released in 1927, is also completely unsettling – though it was laughed off at the time as a ‘silly’ and ‘farfetched’ idea of humankind’s future.

In more recent years, the integration of artificial intelligence programs into society has been met with similar feelings of existential dread. Text-to-image and voice-over apps have already bloated the creative space online, but the thought that more advanced and capable programmes are being shelved away until the ‘right’ time is more worrying, as developers of the likes of ChatGPT and Sora AI (among countless others) admit that they were ready to be released to the public years ago. Creatives also feel threatened by programmes like Dall-E AI and Midjourney, as their works can be instantly matched in quality within seconds by these generators. In addition to this, the general public across the world now seems to feel a profound disconnect between their governments and themselves, stemming in part from the dubious behaviour of tech companies. Yet people will still gladly accept these incredible tools with open arms. Suddenly, one feels glad that ChatGPT is around to help one with various essays, projects, and recipes for cooking.

There lies an inconsistency with how we react to human-intelligence-emulating objects and their use to us. Many want all the power of artificial intelligence – a want that’s never satisfied, leading to the continuous production of evermore advanced AI. However, we are reluctant to confront the fear that artificial intelligence is slowly replacing human experiences with soulless, unfeeling solutions to problems of human life.

The existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre wrote of ‘the look’ – the experience of being seen by another consciousness. This ‘look’ both imparts to us the existence of other minds and augments our own self-awareness. Indeed, feelings such as shame or pride are only understandable if there are other beings in the world to make us objects of scorn or envy. We cannot be judged by inanimate objects; nor can we feel seen or validated by them. This includes digital objects. To feel these emotions, we depend on sentience. Artificial intelligence does not have sentience.

The Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once defined intelligence as ‘the light in the face of others’. In AI’s case, the LED lights are blinding, in that there is nothing within. We interact with a mindless object that reflects to us not what it itself lacks, but what we lack, and this shakes us to the core. As the Australian philosopher Patrick Stokes once wrote, “The truly scary part of AI … is not the thought that we can be replaced by unfree rule-following machines. It’s the intimation AI provides that we ourselves might be unfree as well” (‘Ex Machina’, New Philosopher, 2023).

Air Ship Jean-Marc Côté 1899

New Chains, New Chains!

One of the major figures of the French Enlightenment, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-78), believed that if power really was with the people, then it was the people themselves who should do the ruling. He famously stated, “Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains” (The Social Contract, 1762). Rousseau also believed that it is our own concept of and consequent construction of society that limits us. Laws, taxes, good behaviour, and censorship, seem to be things to keep the average person in line, and society in order. A contemporary addition to the list is the internet. Social media, endless entertainment, and the data detailing each user’s every habit and response, also straighten out any potential acts of freedom. Not knowing the essence of technology makes us unfree, and chained to it.

But is AI really the biggest threat to society right now? After all, we’re the creators of it, so surely its growing power and influence on us can be swiftly dissolved by us? And despite the depictions of AI in films like 2001: A Space Odyssey, I Robot or Ex Machina, artificial intelligence is not innately evil. If AI is mindless, then it cannot possess the capacity to act immorally. So it is not artificial intelligence that’s the problem, I believe, but our own aggressive disposition towards both nature and technology, which changes AI from a neutral object to a more volatile one. The more worrying concern is whether man has an uncurable disposition towards abusing technology.

Technology is now at a level where some fear that it’s doing more harm than good. The infamous Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, argued that “The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race.” We have stepped away from our natural reality, and have insulated, padded, and coddled ourselves with digital distractions – social media, TV, and games. Suddenly we believe we can achieve meaning from these things, when the true path to meaning already surrounds us, in the form of nature.

The great Stoic philosopher and Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius once wrote that “Nothing happens to any man that he is not formed by nature to bear.” Everything humankind has previously been challenged by, it has eventually evolved the ability to remove the danger it posed. Be it bubonic plague, or deadly man-made chemicals, or nuclear warheads, humans have proven that they can either eliminate the threat or learn to live alongside it. In modern society, however, advancements in technology are coming along so fast that we cannot adapt in time to control them accordingly.

Someone who was fascinated with exploring technology’s place in our world was the German existentialist Martin Heidegger, who wrote about technology’s place in our lives in his book The Question Concerning Technology (1954). In it, Heidegger draws attention to technology’s role in bringing about our decline by constricting our experience of things as they are. He argues that we now view nature and human beings instrumentally, seeing them merely as raw materials for technical operations. He believes that modern civilisation has been shackled.

So is there a solution to our self-inflicted restriction of freedom and developing dependency on devices in our lives?

A Transcendental Solution

Transcendentalism emerges as a possible solution, this being a philosophy that emphasizes the importance of the spiritual over the material. Henry David Thoreau was a friend of the father of transcendentalism, Ralph Waldo Emerson. In his defining work, Walden (1854), Thoreau offers some advice on how to escape the chains of which Rousseau wrote. In 1845, Emerson allowed Thoreau to build a small cabin on his patch of land by the Walden Pond of Massachusetts. In his two years there, in his three by four metre cabin, Thoreau discovered a more conscious lifestyle, drastically different from bustling city life. He came to believe that we need very few things, suggesting that we ought to think of how little we need to get by with rather than how much we can accumulate. Following this principle, he even managed to sustain himself by only working one day a week.

Emerson too deeply valued self-sufficiency. In his essay, Self-Reliance (1841), he wrote, “The civilised man has built a coach, but has lost the use of his feet. He is supported on crutches, but lacks so much support of muscle. He has a fine Geneva watch, but he fails of the skill to tell the hour by the sun.” Since man has created various conveniences for himself, he has lost the talents that once came to him naturally – showing that change is not always for the better. But Thoreau went a step further concerning self-reliance, and emphasised the importance of economic independence from the government; and more, that the goal of life is to strip from our lives everything that does not produce fulfilment, ultimately freeing ourselves from the constraints society has put upon us. That also was the aim of Thoreau’s hiatus from normal life: to show others that returning to a pre-industrial, almost primitive, life, was feasible and attractive. He thrived in nature – just as Marcus Aurelius believed every person should.

However, in the modern landscape, with our increasing dependency on digital devices, I am doubtful that the average city person would be able to do such a thing. The film Into The Wild (2007) shows the stark reality of humankind’s current condition, the extreme difficulty even a resourceful modern person has to survive in the wild beyond the comfortable industrial world. Christopher McCandless (Emile Hirsch) struggles to properly cook his meat, not knowing how to drain it or skin it. He fails to forage for fruits and berries correctly, and as a result of eating the wrong plant dies three months into his adventure.

It seems that we as a species have actually lost energy in our efforts to conserve it by using machines, computers, and other conveniences. This is exactly why I believe Thoreau’s transcendentalist approach to modern life to be an answer to the quest for meaning and freedom in a world where neither are the common interests of many. Today, more than ever, consolidating our individual freedom in the world is the most urgent and fundamental need – above and beyond facing any individual threat from machines we ourselves have created.

By drawing from the ideas of Heidegger, Rousseau, Aurelius, and Thoreau, we can begin to navigate the philosophical complexities of our machine-reliant world, acknowledge that we have the power over these objects, and work towards a more informed understanding of what it means to be human.

© Louis Tempany 2025

Louis Tempany is studying acting at The Lir Academy in Dublin.

• This essay won Louis the 2024 Irish Young Philosopher Awards Grand Prize and Philosopher of Our Time award. His video accompanying this essay is at https://youtu.be/VgK4RavL8Ig.