Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Androids At The Cinema

Alessandro Colarossi looks at how Hollywood draws and blurs the line between human and machine.

“Putting his lips together David whistled a few soft, carefully modulated notes. Head cocked to one side, the alien watched and listened. Then it exhaled softly, trying to duplicate the sounds. Since it possessed a very different respiratory mechanism, it failed in the attempt. That did not matter to David. What was important and what prompted him to tears was the fact that the creature tried.”

(Ridley Scott, Alien: Covenant)

One of the dreams in AI is the creation of a machine that’s indistinguishable from its creators. This was the core of Alan Turing’s idea that a ‘thinking machine’ should be able to fool a human that it’s human after a few minutes of conversation across a textual interface. More recent cinematic forays imagine this indistinguishability to be more than merely conversation-based. Popular media representations of AI introduce fully-fledged automata that would be indistinguishable from their human counterparts if it weren’t for the gap between how the robot acts and how it would need to act in order to transcend its mechanistic roots. Inhabiting this ‘uncanny valley’ is a feature of many cinematic androids.

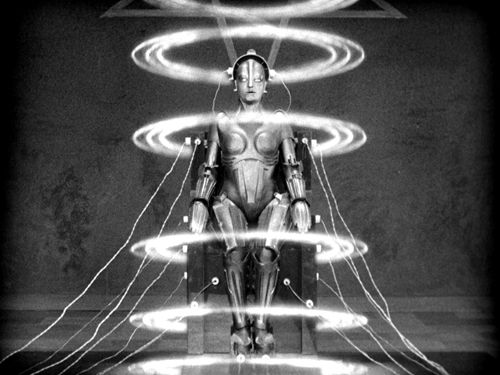

Hollywood has been putting a face to artificial intelligence at least since the groundbreaking 1927 silent film Metropolis, In it, an idealistic young woman called Maria attempts to improve conditions for the factory workers and overcome the class divide between them and the city's rulers. A crazed scientist called Rotwang creates a seductive android. The ruler of Metropolis asks him to use the android to sow distrust among Maria's working-class followers, so he finds a way to exactly capture Maria's appearance and give it to the android. Here we see some of the possibilities of artificial intelligence. The android Maria is a tool of both deception and liberation, an object of love and revulsion in equal measure.

Android Maria gets a wake-up call in Metropolis

Metropolis image © Fritz Lang 1927

Since Metropolis, cinematic depictions of robots have evolved as movie production values have progressed. So too has the emotional complexity with which robots are imbued by their actors. Actors’ portrayals of onscreen robots have developed multiple layers: a human actor playing an android indistinguishable from humans – two characterizations at once, separated by the gulf between nature and technology. Note how far this nuanced idea of a ‘human playing a robot trying to be human’ has changed from the original cinematic conception of robots as mere tin men. The days of expressionless, stiff of movement, monotone-speaking robots apparently are done. Too old school.

One actor who stands out in recent productions as moving fluidly between the natural and the artificial required by an android character is Michael Fassbender. Not only has he played a robot in multiple films, but he’s even played multiple robots in the same film. Most memorably, he portrayed the scheming android David in the 2012 Ridley Scott film Prometheus, a sci-fi horror prequel to Alien. Fassbender reprised the David role in 2017 Alien: Covenant, in which he also played a second android, Walter. David exhibits human emotions, which had been added to his programming in Prometheus with disastrous consequences, but the even-keeled Walter is essentially emotionless. “I wanted Walter to be more Spock-like, devoid of human characteristics or emotional contents that are programmed into David,” Fassbender says: “I want him more like a blank canvas one can project things upon.” In commenting on Fassbender’s performance, Forrest Wickman writes: “Many actors have leapt into the discomfiting chasm between the human and the inhuman… but few actors have as gracefully danced to-and-fro across the divide. He’s such a robot! He’s such a human! That eerie territory has never been so much fun” (‘I, Actor: Cinema’s Finest Robot Performances’, slate.com, June 9, 2012). To prepare Fassbender to play the robot in Prometheus, Scott instructed him to watch three films: The Man Who Fell to Earth, with rocker/actor David Bowie as an alien who never fits in; Lawrence of Arabia, starring Peter O’Toole as a man caught between two cultures; and The Servant, a film in which Dirk Bogarde plays a manservant to a rich, aimless Englishman – of which Fassbender subsequently told Scott, “I get it – I’m a butler.” He also explains that O’Toole’s Lawrence is neither British nor Arabic but an outcast to both. “There’s something in… the robot [David] not being accepted by any of the humans,” says Fassbender, who for the role cut his hair to match O’Toole’s unique Lawrence cut and even internalized some of O’Toole’s mannerisms.

Android twins Walter and David in Alien: Covenant

Alien: Covenant image © 20th Century Fox 2017

Another actor familiar with robot roles is Anthony Daniels, who featured as C3PO in the Star Wars series between 1977-2019. Although his character is a cinematic icon, Daniels can walk down any street in the world unlikely to be recognized, since onscreen he was always covered head to toe with the gleaming gold exterior of the fussy, well-mannered protocol droid. We never see Daniels’ face, but the audience hears him plenty as he flaunts his fluency in some of the seven million languages he knows, whether expressing befuddlement, proudly tapping into his recall, or reacting in stark terror to yet another imminent danger. C3PO is every bit the ‘throwback’ robot, wholly mechanized, with stiff-armed, stiff-legged movements, yet he’s still demonstrably human-like. That’s a credit to Daniels’s keen expressiveness coupled with gifted, often-comedic timing.

This uncanny valley inhabited by Daniel’s and Fassbender’s portrayals is not gender-exclusive. Discussing her portrayal of the robot Ava in Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014), Alicia Vikander says that actors look for parts that will take them out of their comfort zone, which is what she found with Ava in that “she’s a more sublime human.” She adds that if she had aimed for physical perfection in the physicality aspect of her role it would have made her character more robotic. To sell Ava as more human, as a girl – key to the plotline – she took a different approach, making her character more offbeat, with flaws and inconsistencies. She says, “By being a bit more perfect in her movements, she became weirdly enough a bit more robotic. It was not about trying to play a robot while playing a robot, instead about trying to play a girl who is aiming to be a perfect human.”

The theme in which androids or cyborgs attempt to blend in with humans is widespread. A case in point is another Ridley Scott movie Blade Runner (1982). It features four fugitive replicants – synthetic superhumans bio-engineered and implanted with fake memories, but with only a four year lifespan. The replicants escape the off-world colonies in where they had served in various slave-like roles to return to a dystopian Earth to seek more life from their creator. Burnt-out cop Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) is tasked to locate and terminate them. It’s an assignment he takes with reluctance, aware of his prey’s advanced (artificial) intelligence, physical prowess and humanlike emotions. Rutger Hauer plays Roy Batty, the imposing, violent leader of the replicants with a combination of menace and anguish. Also particularly memorable is Daryl Hannah as the ingenue-ish Pris, designed as a ‘basic pleasure model’, but whose deadly acrobatic moves almost end Deckard.

Hauer, who passed away in 2019, called Blade Runner his favorite of the films he was in. He plays his robotic role superbly convincingly; on one hand he’s fearless, making him every bit the daunting foe; on the other, he’s a ‘man’ with a conflicted conscience, who ends a rainy rooftop fight scene with an unexpected demonstration of humanity.

While HAL in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is a mainframe computer not a robot, his remarkably nuanced personality, including petulance, indecisiveness, apprehension, remorse, and dread, present him as plausibly humanlike. His most distinguishing characteristic is his voice – bland, dispassionate, implacable, soothing – all of which makes his menace and deceitfulness all the more disturbing. Like Anthony Daniels with C3PO, we don’t actually see Douglas Rain in 2001, but the voice and mannerisms of HAL are a performance worthy of a Shakespearean stage actor, which Rain was. Rain took a day and a half to record his lines without benefit of interaction with either his fellow cast members or dailies. Instead, Kubrick explained the scenes to him, “giving him only the sparsest of directorial notes… His readings were cool to the point of being chilling, especially as the story moved along and HAL became malevolent” Neil Genzlinger, New York Times, November 12, 2018). In ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ Turns 50: Why HAL Endures’ (Christian Science Monitor, April 3, 2018), Eoin O’Carroll and Molly Driscoll describe HAL as “modernity gone awry, and such a fitting vessel for our collective anxiety about an eventual evolutionary showdown against our own creations.”

Both 2001: A Space Odyssey and Blade Runner received mixed reviews upon their releases, only to eventually be recognised as classics. Both had iconic directors at the helm. Both movies also were unprecedented in their insightful depictions of artificial intelligence.

If there is a common thread to the most intriguing cinematic android portrayals, it is the infusion of character flaws into artificial beings that otherwise are models of mechanized perfection. The possibilities here are conceivably infinite for an innovative actor, given the freedom to paint on a ‘blank canvas’ in whatever manner they choose (at the Director’s discretion). Wickman sees this as an opportunity for an actor to ‘show off,’ to ‘convey life’: “Then there are the layers! There are so many! Rather than merely simulating emotion (yourself), you have to play someone who simulates emotion” (Ibid).

The nuances of cinematic androids are limited only by the imaginations and savvy of their creators in all departments. However, it is clear that the image of robots has moved steadily towards an embrace of subtle artifice. Androids in cinema may have begun with springs and cogs for hearts and minds, but they now regularly feature means of simulating synthetic biology. At the same time, the characterizations of androids in movies have become more nuanced, problematizing the division between natural and artificial that seems reinforced in the very term ‘Artificial Intelligence’. As such depictions continue to develop, we will use cinema as we always have: as a dark mirror reflecting a combination of what we are and what we might become.

© Alessandro Colarossi 2022

Alessandro Colarossi is a technical consultant from Toronto. He is the co-author of Becoming Artificial (Imprint Academic, 2020, becomingartificial.com).