Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

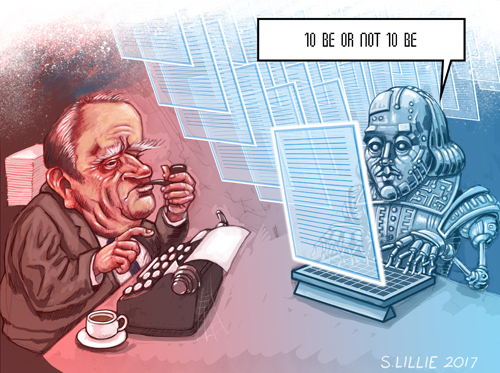

The Rise of the Intelligent Authors

Lochlan Bloom wonders what writers will do when computers become better writers than humans.

Over the past century the pursuit of facts has come to be the central goal of human progresss, with the dominant perception being that facts are important while fiction is at best superfluous. Yet there is increasing evidence that we as humans live our lives in a realm of fictions. It seems we are preconditioned to accept stories and embed them in the deepest fabric of our societies – for example, stories of nationhood, society, economics, or religion. And yet the ability to determine facts is now normally seen as the more vital human trait: facts are important, fiction is superfluous. Reading a book or watching a film of an evening is something to do to relax after a hard day of productivity, a hard day discerning the facts in whatever area of work you are engaged.

But as the philosopher-historian Yuval Noah Harari claims in an interview, “We cooperate with millions of strangers if and only if we all believe in the same fictional stories. The human superpower is really based on fiction. As far we know we are the only animal that can create and believe in fictional stories. And all large scale human cooperation is based on fiction” (youtube.com/watch?v=JJ1yS9JIJKs).

Here I want to argue that the coming rise of artificial intelligence presents a threat to our way of life not only because it is very likely we will become much worse than machines at determining facts, but also because we will, in all likelihood, become worse than machines at creating fictions.

Authors Old & New © Steve Lillie 2017. Please visit www.stevelillie.biz

Recommendations for the Useless

Machine learning algorithms connected to global networks of sensors and data sources will increasingly outperform us when it comes to assessing what is factually correct, whether that relates to stock market movements, the best way to run a company, or the emotional state of a person. At present it takes professionals years of training to identify facts within their profession, and to understand what is a real issue and what is not. So if in the future nobody is trained because machines can analyse the information better than any human, how then could anyone sensibly discuss what is fact and what not?In relation to this Yuval Noah Harari talks about the rise of a ‘useless class’ incapable of doing anything better than machines; and although there is no certainty how technology will play out, it seems undeniable that in future a huge majority of people, from radiographers to economists, will not be needed to do the sort of fact-based jobs we do today. This shift is also likely to be radical when it comes to the most commonly accepted form of fiction, the novel.

Already we are approaching a state where a machine’s understanding of what we read is beyond that of the author in many areas. Amazon can already collect data from millions of Kindles and analyse how a particular reader interacts with a text in terms of which bits we read quickly and where we slow down or stop, and extrapolate this data to provide recommendations based on our personality.

This analysis of the interaction between a reader and a text will only get more finessed as we add more readers and more computing power into the system. As Harari writes in a Financial Times article, “Soon, books will read you while you are reading them. And whereas you quickly forget most of what you read, computer programs need never forget” (August 26th, 2016). Soon the algorithms will know exactly which tracts push your buttons. They will know what you enjoy reading better than you do. Whether you want a thrilling yarn about swords and sorcery, or a enlightening philosophical novel, developed AI will understand precisely which stories you will react to, and will be able to tailor recommendations to you personally.

The Next Step for Authorship

If we take this thought even further, we can see it is not unlikely that once these machine learning tools become available we will then set about re-engineering them so that the machines become the authors themselves. The algorithms may not ‘understand’ what they are writing, but they will be able to calculate exactly what to write to engage our interest, and will construct personalised novels accordingly.

In November 2016 Google announced upgrades to its Translate service which bring it closer than ever to the way humans use language – analyzing text at the phrase level rather than word by word. As Barak Turovsky, product lead at Google Translate, wrote in a blog post, “Neural translation is a lot better than our previous technology, because we translate whole sentences at a time, instead of pieces of a sentence… This makes for translations that are usually more accurate and sound closer to the way people speak the language.”

Once this approach is refined and improved it is certainly not implausible that a machine would be able to produce a whole book. What’s more, a machine could write a book virtually instantaneously. It could write a hundred books. Millions. One for every customer on demand. An endless series of sequels tailored just for you. A made-to-measure novel for your individual personality right now; your ideal read for your mood at the time.

In these circumstances it would be impossible for any human author to compete commercially. What author could possibly make a living? How would a human author produce a best-seller, when a machine can produce a million perfectly designed personalised novels in a fraction of the time? The algorithm will know what you have already read, what you yearn for, what will appear new and fresh to you, and what will appear stale. Who would even bother reading the less personalised work? Well, there may be a sub-culture that enjoys artisanal books, hand-crafted by a human author; but ultimately those books will just not be as enjoyable to read. What then would be the purpose of writing fiction in a world where machines can do it so much better? Will that bring an end to the human desire to create fiction through the act of writing?

An Axe for the Frozen Sea Within

“The fact is that poetry is not the books in the library… Poetry is the encounter of the reader with the book, the discovery of the book.”

Jorge Luis Borges, Poetry (1977)

One possibility is that we will utilize the tools provided by AI to forge a new form of writing. After all, the writing process is not about becoming better at typing, or copy-editing, or learning a series of plot rules or character development concepts. It is (or should be) about precisely those things that machines are now improving at – pushing our emotional buttons. The question is not whether the machines will become better than humans at eliciting a given response, which we assume they will, but which responses we choose the machines to elicit; and so I suggest that the job of the author in the AI age will be determining the best sets of responses to aim to create. For some the novels they choose will be potboilers, containing formulaic, unchallenging thrills; but for others – those seeking an epiphany or a deeper consciousness of the world – the tools to create machine written fiction will be a core part of literature and their exploration of consciousness.

“I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us. If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow to the head, what are we reading for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us. That is my belief.”

Franz Kafka, Letter to Oskar Pollak, 27th January 1904

The technology will soon have the power to enable the more adventurous readers to craft their own path through a constantly evolving literature. With the aid of computer tools, people could even write their own sacred texts, their own books of awakenings. Imagine if every book you read gave you a moment of awakening – provided the axe to the frozen sea inside – instead of spending hours ploughing through books that you realize too late are a waste of time. This can happen if our reading habits themselves became part of the act of creation – an organic never-ending exploration of the possibility of language.

© Lochlan Bloom 2017

Lochlan Bloom is a British novelist, screenwriter and short story writer. His debut novel The Wave is out now.