Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Television

Westworld

Leo Cookman performs an Unheimlich manoeuvre to review a disturbing android saga.

Uncanny is a word with which we’re all familiar, but perhaps slightly misunderstand. We often say that when something or someone is similar to another something or someone, the resemblance is ‘uncanny’, especially if it is one person doing an impression of another. In many ways this is accurate, but it’s normally used in a positive way in this instance. “It’s uncanny!” we may say in wonder. However, when something is truly uncanny there are few things more unsettling.

The concept of ‘the uncanny’ has been explored for centuries, but it was popularised by Ernst Jentsch in his essay On the Psychology of the Uncanny (1906) and Sigmund Freud in Das Unheimliche [The Uncanny] (1919). It is the idea of something that is familiar but just outside the realms of being the same. The etymology of the word ‘uncanny’ stems from the Anglo-Saxon ken (still used in the Scots dialect) meaning ‘understanding or knowledge’; thus ‘uncanny’ is ‘outside of understanding’. Essentially it is something we do not quite understand.

We all know the feeling of the uncanny when someone or something is not quite right. People have reported feeling this in the presence of psychopaths who act in a socially acceptable manner but whom they can instinctively tell are pretending. The disjunct is unsettling. This aligns with an idea that our sense of the uncanny may have evolved in order to help us avoid dangers revealed by that which is ‘not quite right’, including selecting better mates. It’s posited that this also ties in with our dislike of seeing a cadaver; something that looks human but which has no life inside it.

Visiting Uncanny Valley

However or whyever it was developed, it’s a feeling we all know: a fascinated yet uncomfortable feeling of wariness. This repulsion of all that is uncanny is part of our awareness of the world and is part of our consciousness, the very thing that makes us us. To use the language of the philosopher Hegel, the uncanny is a breakdown or blurring of the lines between that which is our Self and that which is Other; between what we understand and what we do not.

For all its possible evolutionary expedience, even today the uncanny prompts some difficult questions. The subject brings up a deeply uncomfortable and shameful aspect of human behavior: how we often shun those who fall into our own category of ‘uncanny’. Thus people with mental or physical disabilities are often ostracised, patronised, or gazed at in rude wonder. For example, the autistic often learn patterns of interaction that they use at perhaps the wrong time: this is seen as not-quite-right, and makes some people uncomfortable. I see this in my nephew who is on the spectrum, and who rather wonderfully, hugs everyone he meets. The feeling of the uncanny could even to some extent explain racism: we see another person, but with a different cadence to their speech or unfamiliar proportions to their facial and other features, and feel an immediate but uncomfortably familiar distance from them which can far too often quickly become a feeling of distrust or dislike.

Uncanny Culture

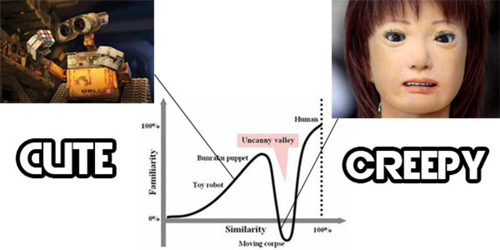

The most famous description of the phenomenon in modern times, is what we have come to know as the Uncanny Valley. The term comes from a graph originally plotted by robotics professor Masahiro Mori in the 1970s to explain the strange sensation, known technically as ‘abjection’, people have when (between certain limits) the more recognisable or lifelike a robot becomes, the more we are repulsed by it. That is, we will accept a robot or an animated character whilst they are still recognisably not human, or if they are not recognisably not human, but as they approximate near realism our acceptance, our like of the machine, drops off steeply. On a graph, this plotting of human resemblance against acceptability looks like a valley in this region of the uncanny.

The concept of the uncanny is used a lot in fiction, both in literature and film, most often and most effectively in the horror genre, particularly those we dub ‘weird’ or ‘macabre’. Think of all the killers in masks or with faces hidden by hair; children behaving just a little oddly; women bent backwards or moving in a jittery way; long, uncomfortable stares; and so on. These are all great examples of the uncanny – something which resembles humanity or is even enacted by a human but is clearly not quite normal.

It is especially seen in horror films from Japan. It is interesting that the uncanny is so prevalent in Japanese culture and that its usage is a tradition there. Their use of masks in certain religious ritual dances and theatre is to many Western eyes distinctly odd, as is the make up of a geisha. Interestingly, when Japanese horror films are remade for Western audiences, they often have a far poorer, less scary effect, usually because the remake has lost the sense of the uncanny that the original dwelled on. With a better developed sense of the uncanny Japanese film-makers are able to access a far deeper level of connection through their art: their use of detachment and abjection makes our attachment and closeness to the real world all the more palpable. If you want to see people react to something uncanny, just put on a mask with almost human features and then interact with them in an everyday setting. You’d be surprised at the visceral reactions this elicits, especially if you’re wearing a Japanese Kagura mask, which is uncanny enough in itself.

A twenty-first century facelift

Westworld images © HBO/Warner Bros Television 2016

Do You Believe?

Another good recent example of the uncanny, and probably one deliberately aligned with an awareness of its true psychological meaning, is seen in HBO’s excellent series Westworld.

Westworld was originally a book and film written and then directed by the late Michael Crichton in 1973. It was about a theme park full of robots who become homicidal. The movie featured Yul Brynner as a killer android whose face eventually falls off, disturbingly revealing the workings within. (It’s surely no coincidence that Jasia Reichardt and Mori’s ‘Uncanny Valley’ essay is from the same decade.) The new TV series takes this scenario of deadly androids as a jumping-off point, but uses it to look more deeply at a bigger question: What does it mean to be human? This is a fairly abstract philosophical question, but is rendered much more real and accessible by comparing and contrasting humans with the android so-called ‘hosts’. An element of what constitutes humanity is considered in how we differentiate between human and host. And through this meditation a more thorough exploration of the uncanny is also enacted.

The performances in Westworld are excellent, in particular those actors playing the robots. It is the subtleties of acting ‘a little off’ that generate our uneasy awareness of their difference from the humans, yet it is even more shocking when this awareness is subverted, leaving us unsure who is what. The scenes that were most horrific and disturbing to me as a viewer were not when the show was bloody or violent, but when a host malfunctioned, to be left twitching, staring, suddenly freezing all motion, or screaming but with no facial expression. The list of shudders is endless throughout the series.

Beneath the mask

Westworld film poster © MGM 1973

In the case of horror, what unsettles us most is the idea that the possibility presented can exist in our own world. Never does this feel more pertinent than with the progress of artificial intelligence and robotics. This is why Westworld is astute in presenting us with the dichotomy of that which is simultaneously both Ourselves and not Ourselves, giving us pause to think about what we accept as real or even human. The staff who are building and fixing the hosts in Westworld are reprimanded by the owner of the theme park (Anthony Hopkins), for covering up hosts with sheets, perhaps to hide their modesty; but is that modesty for the robots or for us, unused as we are to the sight of nudity?

Westworld frequently uses a quote from Romeo & Juliet: “These violent delights have violent ends.” Interestingly, in that same speech, Friar Laurence goes on to neatly encapsulate this idea of the uncanny, saying, “The sweetest honey / is loathsome in his own deliciousness / and in taste confounds the appetite.”

Uncanny Reflections

The uncanny uses an outline, a stencil for our reality and our perception of the world, and yet does not quite fit into this shape, and so is strange and disturbing to us. Abjection is our response. Natural history has taught us to fear what we don’t understand; but I would say, to better understand ourselves, we must better accept and study the outliers. For example, psychologists will tell you the best way to study and understand the normal human mind is to study abnormal psychology.

The robots in the TV series are engaged in a journey toward consciousness, but even humans have yet to understand what consciousness is. Part of the search to understand consciousness is what David Chalmers has called ‘the hard problem’; how there can be subjective experience. But our first step in understanding ourselves would be to confront our in-built fear and rejection of that which we do not understand – of the uncanny. This could be the hardest problem of all.

So far, we don’t really know what we are, but we definitely know what we are not.

© Leo Cookman 2017

Leo Cookman is a writer living in Kent. His poetry has been published in Penguin’s Poetry of Sex, The Best of Manchester Poets, Black Sheep Journal, Ladybeard magazine and Blank Pages magazine, among others.