Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Moral Issues

Moral Decision-Making for a Job Search

Norman Schultz wonders when working is wrong.

Back in 2018 I found myself in an interesting spot. I had decided to leave academia and education to pursue something new in my working life. Despite the downsides, it’s easy to feel morally comfortable with being a teacher, but many other jobs can give pause. The timing and my background placed me in a near perfect position to think about how ethics factors into choosing a career. So on what criteria does one base the moral legitimacy of a job? I realized that:

1. Many people take jobs they aren’t morally comfortable doing.

2. There probably are some truly immoral jobs – by which I mean, perfectly legal jobs no one should take.

3. People use a common set of reasons to justify morally questionable employment.

I suspect most people don’t look at the job market this way, probably due to personal preference – “I don’t judge others, but I wouldn’t feel right doing that for a living.” But in the interconnected world, one’s work can affect an enormous number of people. So if a job is immoral, performing that job could do quite a lot of harm. I want us to explore these matters here.

What Do I Mean by ‘Job’?

One might think that the subject simply reduces to a more general consideration of moral theory, in that I’m really asking on what criteria we correctly judge right and wrong at all. But there are relevant particulars to employment that weigh in on making a moral evaluation there. The fact that most people must work and each worker is often just one player in a large industry complicates matters. But first and foremost, I must clarify what counts as ‘employment’.

Let’s leave illegal activities out. Yes, being a pimp, thief, or con artist may be your central source of income, and as such you might call it your ‘job’. But I would sound silly arguing for the idea that illegal ‘careers’ are morally questionable, if for nothing more than the fact that they are illegal. So even if counterexamples could be found, I won’t address them here. I see both myself and most Philosophy Now readers as unlikely candidates for an outlaw lifestyle. More importantly, I think it’s much more interesting to ask, Are any legal jobs immoral to take?

I also must clarify that my goal is to examine employment types, not employment instances. A teacher, nurse, or dentist might themselves happen to be bad, and may harm people through their work by engaging in abuse or fraud – but their job type is morally upstanding. A lawyer who writes intentionally obfuscated license agreements, or a marketer writing deceptive product labels, is doing something immoral, but their job type doesn’t require them to be deceptive or impenetrable. Or a convenience store clerk may have a moral obligation to attempt to dissuade a pregnant mother from buying cigarettes, but there’s nothing wrong with simply being a store clerk. But these examples are outside the scope of this essay. I am looking for how to condemn or condone entire job classifications. Job advertisements for these positions should go unanswered, and anyone taking these jobs should be watched.

This doesn’t narrow things down much. Speaking only of legal work, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics classifies 867 different job types. Statistics Canada, by contrast, lists over thirty thousand. This reminds me of the beginning of Descartes’ Meditations, where he proclaims that he must not “survey each opinion individually, a task that would be endless.” In this case, not literally endless, but certainly highly tedious, and unnecessary if I can examine these matters wholesale by creating a general set of criteria to categorize immoral employment. If I propose the right criteria, I should then be able to provide real-life examples of immoral jobs.

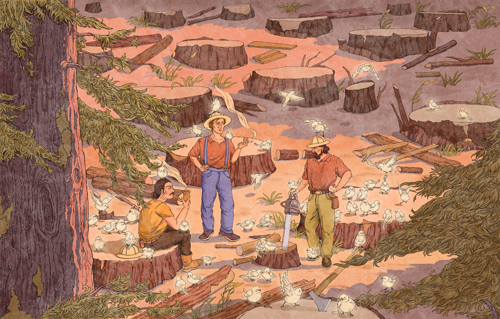

Legal Work, Silent Witnesses by Melanie Wu

Immoral Does Not Equal Illegal

It might seem initially strange to claim that some perfectly legal jobs could be immoral. Industrial regulations that ban certain kinds of practices usually do so on moral grounds. Laws that reign in business activities are tied to morals because they weigh in on how companies affect others, for example, with respect to health, safety, or the environment. Such laws exist at every municipal level. Companies that lie, cheat, or harm people get punished – right? This all seems like a subset of moral rules enforced through law. But some straightforward thinking tells us that law and morality aren’t co-extensive.

Laws represent a body of written rules: bills are proposed, votes are taken, and after a law is in place, courts interpret them. But mistakes are made. The law might not have caught up with a rapidly advancing industry. Technological sophistication may hide wrongdoing from legislators and the public. Or maybe the industry has good lobbyists. In this way, an immoral form of work might be perfectly legal as a result of a series of poor decisions or bad actors. Law-making is an imperfect process, so a body of laws will likewise never be perfect. Morality, though, is defined through a set of concepts. Determining those concepts, on which the entire field of morality rests, is notoriously difficult: a system of morality must be argued for, and what fits into it must also be convincingly clarified. But, assuming there is objective morality at all, morality itself (whatever it turns out to be) is perfect – because it is based on logical relations between ideas, not consensus, historical events, or stored records. If something is morally wrong, it is so regardless of public sentiment or popularity. (This is not the same as saying it’s easy to know what is moral and what is not. It isn’t always, clearly.)

There are acts that are immoral but for very good reasons are not illegal: should we lock up people who lie to their parents? The same thought can apply to industry. Certain kinds of morally-justifiable industry regulation may be impractical, impossible, or undesirable for some other reason. A cure can be worse than the disease. For example, even if it would be morally best to take handguns away from the average US citizen, the amount of intrusion and force it would take to accomplish this might result in an even more violent society. It’s possible to let a genie out of a bottle before you know what the genie is up to; just so, it might be too late to regulate the US gun industry in certain ways. But none of these practical matters need apply to our moral judgement of an activity, business-related or otherwise.

Morality doesn’t equal law, and law doesn’t equal morality. So we can fully expect there to be some perfectly legal jobs that would be immoral to take.

On What Basis Can We Morally Judge Employment?

Let me propose a set of criteria by which one may judge a job to be morally abhorrent. While I could inductively say that the more criteria being met, the more likely the job is immoral, I will take the more cautious approach, and say that a job meeting all these conditions is a clear case of one that should be ethically avoided.

The first criterion is:

1. A job that harms people, directly or indirectly

Most morally objectionable actions are so because they harm others. Stealing, lying, breaking agreements, causing physical harm, etc, without some overriding reasons, are immoral. Yet most jobs directly or indirectly help others, providing something desirable. People seek the products or services offered because they believe them to be beneficial.

Work directly helping others, such as being a nurse or a social worker, is indeed morally commendable. Indirectly helping others is also easily applauded. Bioengineers or epidemiologists, though never seeing individual patients, or perhaps even curing any specific ailments, may help a great many people. These kinds of professions are noble and morally praiseworthy, and most people who get into them are not thinking only in terms of purely selfish gain. Even work that is commonly maligned can be tied to benefits. People who test people’s ability to drive don’t exactly have a reputation for ‘good customer service’, but their work protects us all. We also wouldn’t want to live in a society that makes it easy for drivers to flee accident scenes in unregistered cars.

What about industries that cater to people who want to be harmed? A masochist pays a dominatrix to cause them pain; and there are plenty of consumers of cigarettes, alcohol, and fast food. But setting aside puritanical sensibilities for liberal ones, I think we can’t find fault with the dominatrix, the fast-food worker, liquor store clerk, or smoke shop owner.

Really this is a language matter, largely solved by ethicists via the concept of preference satisfaction. (For a classic defence of this idea see R.M. Hare’s 1981 book Moral Thinking). From a certain liberal perspective, you’re not harming someone if you satisfy their informed preferences. Specifically, the word ‘harm’ is not synonymous with ‘pain’ or even ‘shorter life’, so one can make sense of saying the masochist isn’t really paying to be ‘harmed’, because the pain is exactly what he prefers. Cigarettes, alcohol, and fast food also represent a pleasure trade-off.

At this point it should be evident that the concept of ‘harm’ is philosophically contentious. Numerous works have attempted to address how to define it. One particularly influential work, ‘Doing Away with Harm’ by Ben Bradley (Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol.85, No.2, 2012), proposes that philosophers should stop using the concept of harm altogether, due to its difficulties. I believe this to be an extreme view. I do not agree with Bradley when he declares that a philosophical definition must fit every common use of a word. It seems perfectly possible that an analysis of a concept could arrive at a precise definition and in so doing reveal that people unknowingly use the word metaphorically or incorrectly. A clarifying definition might be offered, but be unpopular because people (which includes philosophers) don’t like its implications. So I believe the concept of ‘harm’ is useful despite its problems.

I’ll define ‘harm’ as ‘that which foreseeably risks diminished quality of life’. I accept that this defines a complex word using complex words, but the definition works. If in playing darts at a pub I land one in your leg, I harmed you, because of the risks, regardless of whether you recover without long-term damage; but I don’t harm you in selling you a cheeseburger because you purchased it knowing the downsides, and you’re responsible for how you define the quality of your life. I don’t harm you if I offend you by telling you what you don’t want to hear if its possible that you later benefit from the advice. And I don’t harm you if I delay your drive by three seconds by safely changing lanes, even if ten minutes later you get into a car accident that would have been avoided if you had been there three seconds earlier.

Under this concept of harm, morality invokes the important notion of informed consent. So selling alcohol, cigarettes, or fattening fast-food is not immoral if the health risks are transparent and consumers know what they’re doing. But we do speak of jobs that ‘take advantage’ of others. These seem to be cases where we allow ourselves to be harmed because we don’t understand the harm. So deception must be involved. This brings us to our next criterion of an immoral job:

2. A job that requires intentional deception

A job category or an entire industry that deceptively takes advantage of customers for profit is perhaps the strongest candidate for moral censure.

It seems obvious that doing harm via deception is morally wrong. And when laws are working properly, such industries and practices are usually made illegal: it’s illegal to hide the harm a medical treatment does, or lie on your listed ingredients and sell bread laced with heavy metals. Because the law tries to eliminate harm-causing deceptive practices, one might initially think it difficult to find clear legal examples of this sort of unethical work. But the issue of deception brings up an interesting question: What if there’s deception but no clear harm?

Two examples that come to mind here make for strange bedfellows: police detectives and party planners. Both engage in deception in the normal course of their work. Detectives frequently use deception as a means of getting confessions or information. While there is quite a lot of debate as to how far police may legally and ethically use deception to gather information or gain a confession, the discussions generally assume some level of deception in some circumstances to be legitimate. Would we really want detectives hamstrung by a policy of strict honesty when working undercover? I also don’t think we want to require the event planning industry to ruin our surprise parties. This is, of course, contrary to Immanuel Kant’s ethical ideas: he argued that lying is always immoral regardless of any beneficial end. However, such an absolute no-lie ethos seems counter to what morality intends to accomplish. On the contrary, for deception to be a source of moral wrongness, it must be connected to some kind of harm.

To what lengths we morally must go to avoid deception is itself an interesting subject. The subject of ‘disclosure’ in the seller/customer relationship is a known issue in business ethics; for example, in considerations of product labelling. To clarify its scope, let’s employ a simple example: a yard sale. Let’s say you’re having a yard sale and want to get rid of a blender you don’t like. In fact, you know the model is poorly made – the details of which you’ve seen are readily available in online reviews. Are you morally obligated to warn people of the design flaws whenever someone shows interest in it?

This is, I think, a grey area. The most information I’ve ever seen at any yard sale, is that an item works at all, and even with that you probably shouldn’t buy it without at least a rudimentary test.

This is all standard. Caveat emptor (‘Buyer beware!’) applies, and shoppers implicitly agree to the risks of shopping. As such, seller obligations are minimal. But there are limits. I think avoiding intentional deception by warning others of known possible harm is a moral obligation. even at a yard sale. (This is one reason I don’t like to buy things from yard sales: almost no one embraces this moral requirement.) So it would be wrong to sell a blender you think might explode, or a lawn mower with a loose blade. But generally, you morally can sell it if you clearly warn potential buyers, and in so doing avoid any deception. The responsibility then rests on the buyer (hopefully they’re a tinkerer). However, there are some cases where it’s morally wrong to risk harm even if the buyer would allow it, since some items are so potentially harmful that no-one should sell them: it would be very bad indeed to sell a high-powered laser or a vial of smallpox at a yard sale. But this is a quagmire I need not dive into, because the clearer case of intentionally employing deception that causes harm is the most solid example of immorality.

The last criterion is:

3. A job that plays a key role in a morally troubling industry

The character of our work effectively takes on the profile of the industry and company we work for. Two people might both be engineers, but ethically speaking, the one who designs MRI scanners is quite different from the one who designs landmines. The objective of the company and its industry matter.

Many professional roles contribute to the general working of a company, but only some are key, meaning that they fundamentally contribute to making the industry what it is. A receptionist working in the munitions industry will be hard to categorically condemn because of their limited role in making weapons. Pursuing such condemnation would surely create an argumentum ad absurdum: should the local office supply store refuse to sell the company printer paper? Should a postal worker stop delivering their mail? Maybe the receptionist would do better to work somewhere else; but if the company’s behavior is immoral, it’s not because of the receptionist. It therefore seems necessary to count as immoral only employment in which a person knowingly and willingly contributes to whatever is morally wrong about the product or service provided. Or to put it another way, the key players in an industry are the reason their office needs receptionists, printer paper, and mail delivery. As such, the key players bear the bulk of whatever moral responsibility applies to their work.

Also, the previous criterion regarding deception includes the word ‘intentionally’. This is important in a professional context because not everyone involved in a business may know what the business is really doing. An admin assistant or in-house chef working for an aerospace company probably doesn’t have detailed knowledge of what the company makes. The specifics might be classified or otherwise secured from most employees, or the technology may be incomprehensible to non-specialists. As such, I don’t think it makes sense to view everyone working at a problematic company or in a troubling industry as moral equals. The particular job they do seems relevant. At the very least, an employee has to know the morally troubling aspects of the company’s activities to be held as an accomplice in those activities. Only then are they complicit in any deception or other immorality involved.

Image © Susan Auletta 2025 Please visit instagram.com/sm_Auletta/

Rationalizations

People take morally questionable jobs. Here are some common justifications made for doing so:

“If I don’t take the job, someone else will. It might as well be me.”

This reasoning seems both morally troubling and substantively incorrect. If no one takes a certain job, that industry would have to change to accommodate the fact. And because of supply and demand, the issue isn’t so binary. As fewer and fewer people are willing to do a job, the wages for it have to increase until either someone will take it or it has to be given up on. By not taking a morally reprehensible job you therefore send the message that it should go away, and contribute to making it harder for employers to continue in their immoral activity.

“I’m supposed to look out for myself. I need this job.”

It’s telling that the same could be said of illegal jobs, such as an assassin or a human trafficker. Under capitalism, we all indeed have to look out for ourselves by seeking gainful employment. But it seems highly unlikely that the only option available to most individuals will be to take an unethical job. The real reason this rationalization comes up is likely that the unethical job appears to be the most lucrative one available.

This justification is actually a subset of a common justification for being immoral: self-interest. If acting in self-interest were a sufficient reason to override being ethical, ethics collapses entirely.

“I want to change things from the inside.”

Although this is a reasonable response for a small subset of jobseekers, it is unrealistic for most. The validity of this reason stands only so long as it is realistic that you will be able to change things. Being hired into a managerial or a senior-level position makes making change a real possibility, but less so as the rank decreases. So for most people this would be an unrealistic rationalization, which can be exposed by some sober thinking about what will be in your control in the new role. It’s notable, too, that this reasoning leads to an obligation to leave a position when it is determined to be impossible to enact sufficient change.

Concluding Thoughts

While working on this essay, numerous real-world examples of jobs that might be unethical came up. Video slot machine programmers, payday loan officers, corporate lobbyists, psychics (especially those who claim to talk to the dead), homeopaths, televangelists, marketers to vulnerable populations (especially children), and paparazzi, were all possibilities. Hopefully the analysis I’ve provided can assist in determining which careers are to be avoided. It’s also possible to use these criteria to judge employment at a specific company whose goals are not themselves immoral, but which has a culture of immoral behavior. To knowingly work for a company that engages in unethical behavior to gain an advantage over its competitors would likewise be morally wrong. The company culture might be difficult to judge from the outside, so taking a job with them might well be blameless – but once an employee knows the immorality the company is up to and their own role in enabling it, they would be obligated to seek employment elsewhere.

At the very least, we should all spend some time thinking about the ethical implications of the jobs we take up, and the professional directions we encourage others to pursue.

© Norman Schultz 2025

Norman Schultz has an MA in philosophy from the University of Colorado at Boulder, and is a former Philosophy Instructor for the Metropolitan State University of Denver. He is now retired, in France.