Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

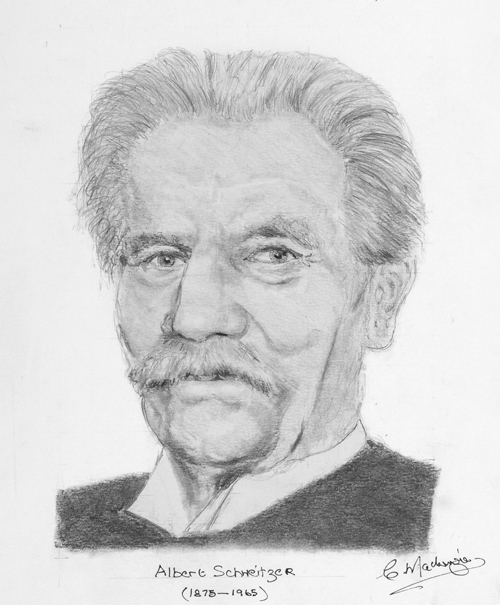

Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965)

Colin Mackenzie surveys the full life of a philanthropic philosopher.

Albert Schweitzer was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952 for his humanitarian work as a medical missionary in Gabon, Africa. The impulses which led him to a life of service gradually evolved into his philosophy of ‘Reverence for Life’. Here I want to show some brief reverence for Schweitzer’s own life.

A Life Begins

Albert Schweitzer was born on 14th January 1875 in the small village of Kaysersberg in Upper Alsace, North Eastern France. Not long after his birth, the family moved to Gunsbach in the Munster valley, which now houses the headquarters of the Albert Schweitzer Association. His father was a Lutheran pastor, his mother the daughter of a pastor, and several of her family were church musicians. As well as a religious upbringing, Albert’s development and education was also shaped by his maternal grandfather’s love of organs and organ building. Schweitzer’s musical talent showed early. At five he received piano lessons from his father, and by the age of eight he was playing the church organ.

Around this time an incident took place that had a profound effect on him. Schweitzer and his friend made catapults, and his companion suggested that they go to shoot birds with them. Fearful of being mocked for refusing, he went along; but when the moment came to shoot, the bells of the local church rang out, and suddenly, instead of shooting the birds he shooed them all off, threw away his catapult, and ran home. Later Schweitzer said: "ever since then when the passiontide bells ring out… I reflect with a rush of grateful emotion; how on that day their music drove deep into my heart the commandment: ‘Thou shalt not kill’.” (Out of My Life and Thought, 1933). This incident had a profound and lasting effect on him, as will become evident.

Schweitzer received a sound education, which included attending the Gymnasium at Mulhausen in Alsace. After graduating from the Gymnasium, his uncle obtained for him an audition with Charles-Marie Widor, the famous organist of Notre Dame, who did not normally take students; but on hearing the young man he accepted him as a pupil.

However, Schweitzer was disturbed by other thoughts. To him it was incomprehensible “that I should be allowed to live such a happy life, while I saw so many people around me, wrestling with care and suffering” (Out of My Life and Thought). He decided that from the age of twenty-one he would devote himself to art and science until he reached thirty, and from then on devote himself to the service of others.

At eighteen, in 1893, he entered Strasbourg University to study Theology and Philosophy. He had a high opinion of Immanuel Kant, whom he saw as the greatest philosopher of the modern era because of Kant’s intellectual integrity and his dedication to reason wherever it may lead. He was also impressed by Kant’s ability to show limits to theoretical knowledge, and Kant’s idea that we cannot reason our way to all metaphysical truth. Schweitzer decided not to read the literature about Kant, but to engage directly with his writings, principally the Critique of Pure Reason (1781). He adopted a similar approach in his theological studies, and also in his study of Bach.

In 1902, already a Lutheran Pastor, he was appointed Principal of the Theological Seminary in Strasbourg. In the same year he met Helene Bresslau, who would eventually become his wife.

A Medical Turn

Schweitzer was troubled by accounts of the appalling treatment of African peoples by their colonial masters. So although a brilliant academic career lay ahead, he decided in 1905 to study medicine to go as a medical missionary to serve the people there. He happened to see an appeal in a magazine for missionaries to go to Gabon. His decision to head there was met with formidable opposition from family and friends, because they saw a successful career in Europe ahead in theology, philosophy, and music.

Yet there seemed to be no limit to the stress Schweitzer was willing to endure. While studying to be a doctor, he continued to teach theology at the university, and preach, while also researching St Paul. As a founder of the Paris Bach Society and its regular supporter, he was chosen to play in their concerts, which involved trips to Paris from Germany. Early in his medical course he also wrote an essay on organ building.

Schweitzer sat for his exams in anatomy, physiology, and the natural sciences, and passed as a result of intense cramming. He then moved on to clinical studies. Before taking his final exams, he applied to the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society, but was rejected. Apparently his theology was unacceptable, however, having given his word that he would only heal and not preach, he was eventually accepted. In October 1911 he took his final exams.

A Significant Side Quest

While he was studying medicine, Schweitzer’s book The Quest for the Historical Jesus (1906) was published. In it he rejected the contemporary views on Jesus – both the conservative approach, and the liberal approach that tended to remould Jesus in its own image. In the book he concluded that the Jesus of history is unknowable, and it’s only by accepting the spirit of Jesus that we can begin to see him. This is not knowable through doctrine but only through ethical action based on a reverence for life. It’s not a love of belief nor a love of self, but a love based on respect for life. For Schweitzer this was the true message of the gospel.

Schweitzer concludes his Quest with this eloquent statement:

“He comes to us as one unknown, without a name, as of old, by the lakeside, he came to those men who knew him not. He speaks to us the same words: ‘Follow thou me’, and sets us to the task he has to fulfil for our time. He commands – and to those who obey him, whether they be wise or simple, he will reveal himself in the toils, the conflicts, the sufferings, which they shall pass through in his fellowship, and as an ineffable mystery, they shall learn, in their own experience, who he is.” (pp.127)

Albert Schweitzer by Colin Mackenzie

Back to Bach

Schweitzer was fortunate to acquire a complete edition of JS Bach’s works, and on one of his visits to his friend Widor, promised to write a book on Bach for the students of the Paris Conservatoire. It proved to be so successful that he later wrote a fuller two volume work in German, which was published in 1908.

For Schweitzer the music of the Baroque reached its ultimate expression in Bach, but also he saw him as a poet, expressing the inexpressible through the medium of music. He also saw Bach as an artist, because in his choral works and chorales (Lutheran hymns) Bach expresses the deepest meaning of the text through harmony, musical figures, and motifs.

Marriage, Medicine & Morality

In 1912 Schweitzer married Helene Bresslau, who was an enormous help to him. She shared his values and concerns, and as well as a social worker and nurse, she was Schweitzer’s helper and companion through all their preparations for Africa, and in Africa itself.

On Good Friday 1913 they at last set sail, their destination Lambarene, nearly fifty miles up the Ogooue River in western Gabon, where the Schweitzers would open their hospital. On arrival they were besieged by patients with: malaria, leprosy, sleeping sickness, dysentery, and many other illnesses. They acquired a room which they transformed into a consulting and operating area, and began treating the seemingly endless stream of people. Then, in 1914, just when they were settling into their work and making progress, war broke out. The Schweitzers were placed under house arrest; but as a result of protests from their patients, were soon allowed to continue their work.

Around this time Schweitzer was asked to visit the ill wife of a local missionary. On a long, slow journey upriver, he mulled over his time in Africa and the philosophy he had read and struggled to find an adequate ethic. None satisfactorily addressed a way of living that incorporated the spiritual, ethical, and practical sides of life. He had also become extremely critical of European civilization, which he saw as in decline from the high ideals of the Enlightenment. He believed that for all people to reap the benefits of material progress, the will to advance civilization must be ethical. But instead, the nations of Europe were nationalistic, arrogant, militaristic, and power-hungry. Their pride and willingness to go to war were blessed by many who should have known better. The outbreak of the Great War provided terrible proof of their error.

From the outbreak of World War I, many related thoughts occupied Schweitzer’s mind as he filled pages of disconnected notes. He recounts: “I sat on the deck of the barge, struggling to find the elementary and universal conception of the ethical which I had not discovered in any philosophy” (Out of My Life and Thought). Then:

“Late on the third day, at the very moment when, at sunset, we were making our way through a herd of hippopotamuses, there flashed upon my mind, unforeseen and unsought, the phrase, ‘Reverence for Life’. The iron door had yielded: the path in the thicket had become visible. Now I had found my way to the idea in which affirmation of the world and ethics are contained side by side. Now I knew the ethical acceptance of the world and life, together with the ideals of civilization contained in this concept, has a foundation in thought.”

Civilization & its Displacements

But worse was to come for the Schweitzers: as German citizens they were transported to France as prisoners of war. This was a very difficult time for the couple, both were ill, exhausted, and dispirited and Helene had contracted tuberculosis. During this period, Schweitzer began work on his Philosophy of Civilization. After a time they were permitted to return to Alsace. They stayed in Europe between 1919-1924, to recover from their ordeals and rebuild their lives, but also to rejoice in the birth of their daughter Rhena. The Philosophy of Civilization was published in 1923, and Albert began fundraising for an eventual return to Africa.

Helene’s health and medical care meant that even back in Europe the couple were often apart. A return to Africa for her was out of the question; but not for Albert, who set sail for Gabon to restart the project they’d been forced to abandon. This was a difficult time for them, but Helene continued to fundraise and promote their work. After a couple of years, a new hospital was built.

Albert remained there until 1929, when he returned to Europe, exhausted; but it wasn’t long before he began to fundraise again and give lectures. He went back to Lambarene the following year, and stayed there for almost ten years, returning home just before the start of the Second World War, and this time remaining in Europe for ten years. But in 1949 he was back in Lambarene, where he remained until his death, with just occasional brief trips to Europe.

He was presented with the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953 (awarded 1952). Helene, his faithful supporter, died in 1957. Albert himself died at Lambarene in 1965, where both Helene and Albert are buried. Rhena took over the administration of the hospital, which still serves the people of Lambarene today.

Reverence in Brief

Schweitzer approached philosophy from a Christian perspective, and his service was a practical expression of his philosophy. But he also believed that Reverence for Life as a universal ethic can be approached from other religious viewpoints, or from none. For Schweitzer, “Ethics is nothing other than Reverence for Life.” He accepted that we live and have always lived at the cost of other lives. We cannot escape these choices, as we are inheritors of our ancestors’ survival instincts: but that is not a licence to needlessly take life. Putting all life first, as Reverence for Life insists, changes the perspective: “The circumstances of the age do their best to deliver us up to the spirit of the age, and we treat life as if it were not life, making plants and animals subjects for our gratification”, wrote Schweitzer: “We must extend our compassion to include all living things; until this is done, mankind will never find peace” (The Quest of the Historical Jesus, 1906).

© Colin Mackenzie 2025

Colin Mackenzie is a retired schoolteacher, a musician, and an artist, with a lifelong interest in Schweitzer’s philosophy of Reverence for Life. He lives in Dublin.