Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

Hilarius Bogbinder considers the all too human life of the notorious iconoclast.

“The last two weeks were the happiest of my life” (Letters, 321) wrote Friedrich Nietzsche. The year was 1884. He was completing what he himself considered his greatest work, Thus Spoke Zarathustra. There can be no doubt that this son of a Lutheran vicar was moved to almost religious ecstasy when he composed the book, even if he had lost his faith while a student of theology. Unfortunately, when it was published, the tome, dedicated to ‘all and nobody’, seemed to only be for the latter. Now, over 140 years later, it is probably known about – if not understood – by the former (at least in academia). In a sense, that is odd. Famous and revered, Thus Spoke Zarathustra also contains some rather peculiar observations, such as, “Is it not better to fall into the hands of a murderer, than into the dreams of a lustful woman?” (p.78) – to which most people would answer “No”. Little wonder that Nietzsche, perhaps in a moment of self-reflection, commented in his subsequent book, Beyond Good and Evil, “that all philosophers have had little understanding of women” (p.3). Yet of course Nietzsche would not also have gained his reputation if the book had not contained more insightful observations, and a life-affirming exuberance that we rarely see in philosophy. Who but Nietzsche could write, “You must have chaos in you to give birth to a dancing star” (Zarathustra, p.19)?

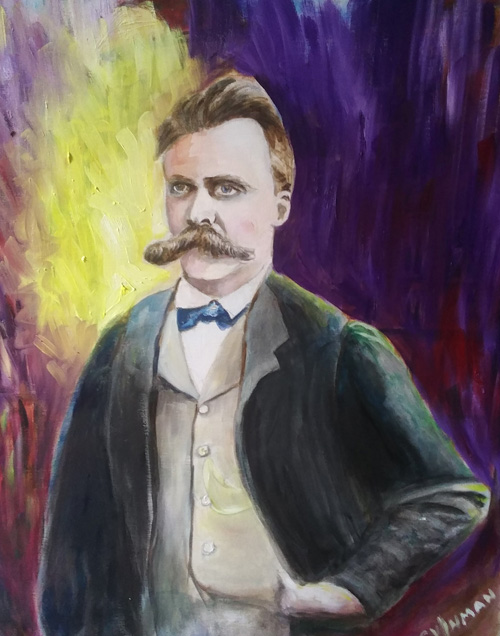

Friedrich Nietzsche by Clint Inman

The Philosopher Dances

Like all great thinkers, Nietzsche’s philosophy grew gradually.

He was a prodigy from the beginning. He won a scholarship to Schulpfortam, Germany’s most prestigious secondary school (a bit like Eton in England), then went on to study Classics with exceptional bravura, having dropped out of his divinity course in the first year after he read Arthur Schopenhauer’s World as Will and Representation (1818). Schopenhauer’s explanation of the world as ‘blind will’ changed his life. That pessimistic philosopher’s belief was that we live in a chaotic universe, so that we are “freely floating in boundless space, without knowing whence or whither, and to be only one of the innumerable similar beings that throng, press and toil restlessly and rapidly arising and passing away in beginningless and endless time” (Will and Representation Vol II, 3). This shook Nietzsche’s faith in providence and the Christian God.

Having been elevated to a Chair in Classical Philology at the tender age of twenty-four (though he never formally completed his doctorate), this philosophical Wunderkind soon tired of academic life and longed for laughter and joy. Unlike Schopenhauer, who remained cynical and anti-social, Nietzsche had an appetite for living. For the former, art, in particular music, was the only respite from an otherwise unbearable life without meaning, as it “expresses the storm of the passions and the pathos of feelings” (Will and Representation II, p.448). Music was Nietzsche’s passion too, but in a life-affirming way. He found this particularly in Richard Wagner’s operas. Inspired by the German composer, the young professor burst onto the scene as a writer with The Birth of Tragedy Out of the Spirit of Music in 1872. In this brief book he juxtaposed Dionysian wildness with Apollonian reason as the forces behind Greek theatre. Philosophy itself had been focused solely on reason, but humans also have a lust for life. Sure, we need reason, but we must also have passion: “Singing and dancing, man expresses himself as a higher community” (Birth of Tragedy, p.18).

It was this same spirit he expressed a decade later in Zarathustra – except he did so in almost Biblical language and with a poetic sense that’s on par with Goethe, Rilke, and other supreme German stylists. Which other philosopher could write, “The night has descended: now flows the frolicking brooks. My soul too is a frolicking brook. It is night: now all the songs of lovers come out. My soul too is the song of a lover” (Zarathustra, p.153)?

In his autobiography, Ecce Homo (‘Behold the Man’, 1888), Nietzsche reflected that “The whole of Zarathustra might perhaps be classified under the rubric ‘music’. At all events, the essential condition of its production was a second birth within me of the art of hearing.” It was an “essentially yea-saying pathos” (p.97). One gets a sense of this in the closing bars of Zarathustra, where Nietzsche, intoxicated with pathos and eloquence, exclaimed, “The world is deep and deeper than day. Deep is its sorrow, longing even deeper than the song of the heart” (p.419). Zarathustra itself had that effect on others: for instance, the book inspired the ‘tone poem’ Also Sprach Zarathustra by Richard Strauss in 1896, music which was later made famous as the theme of the film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

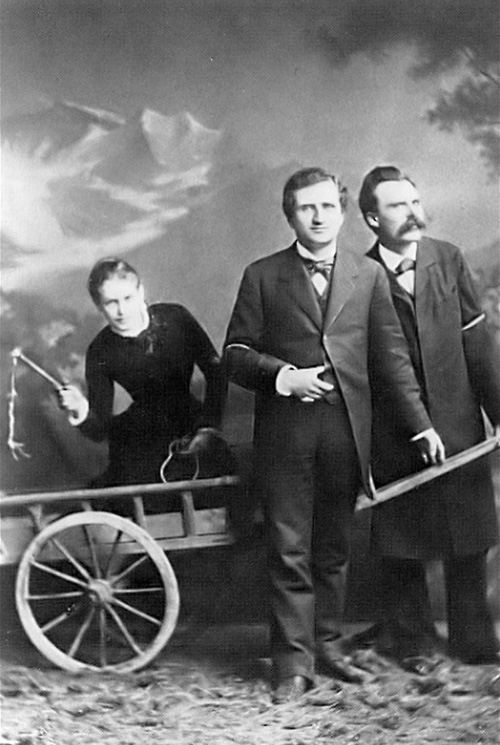

Supremely musical Zarathustra might have been, but it should not be overlooked that personal circumstances played a significant part. Nietzsche almost admitted this when in his autobiography he confessed that the book was a result of “the astounding inspiration of a young Russian lady, Miss Lou von Salomé” (Ecce Homo, p.98). Nietzsche had lived in a rather unconventional threesome with her and his friend Paul Rée. What Nietzsche did not reveal in his autobiography was that he had proposed to Salomé and been rejected. So Zarathustra was written, at least in part, with a broken heart.

Terrible Revelations

It wasn’t the only thing that had been broken. Nietzsche had been a regular visitor to Wagner’s home in Bayreuth; but when the composer embraced Christianity in his opera Parsifal (1882), Nietzsche severed his ties with his erstwhile friend.

Nietzsche had seen Wagner’s music as a cure for German cultural decline. Now he became rudderless. After a brief flirtation with the ideals of the Enlightenment in Human, All Too Human (1878), he wrote The Gay Science (1882) with a changed outlook. In this book he discovered – with terror – his idea of the Eternal Return – the idea that “this life, as you live it now, you will have to live again and again, times without number” (p.341). The other revelation from that book which shocked him to the core was ‘the death of God’. In a famous section he described a ‘mad man’ who was running through the streets in despair, declaring the death of the deity: “we have killed [God]… how shall we… console ourselves?” (p.125). Zarathustra was a boisterous and cheerful answer to the mad man’s question.

Nietzsche clearly saw the two books as companion pieces. Indeed, he almost self-plagiarised. He introduced the character of Zarathustra in the final pages of The Gay Science, and described how the sage, after years of solitude, greets the sun with the words, “Thou great star, what was thy happiness if thou shinneth for no one?” (Gay Science, p.342). The exact same words feature on the first page of Zarathustra.

But the focus is different. Whereas Die Fröhliche Wissenschaft (as it’s called in German) is anything but ‘joyous’ or ‘gay’ (froh), Zarathustra, by contrast, is written with messianic zeal, in the style of Jesus’s Sermon of the Mount, with its hero as a prophet. The book even contains a chapter called ‘The Last Supper’. Taking aim at Christianity – but without being explicit about it – he teaches his followers that “he whom they call redeemer has cast them into bondage” (p.131). He also says that to live in a godless universe, we must not despair but embrace the idea of the Übermensch – the ‘beyond human’ who comes to terms with the crass materialism that “the soul is only a word for something in the body” (Zarathustra, p.46).

For the Übermensch, the Eternal Return, which in The Gay Science Nietzsche called ‘the heaviest burden’ is now cast in almost eschatological exultation: “Everything goes, all comes back – forever rolls the wheel of being. Everything withers, and all blossoms anew – forever runs the year of being. Everything goes, and all comes back, true to itself the ring of being” (Zarathustra, p.317). So having uncovered ‘the Eternal Return’ and ‘the death of God’ in The Gay Science, Nietzsche set forth a new gospel for unbelievers, and did so with the poetic eloquence of holy books, often using biblical expressions like ‘Verily I say onto thee…’ and other Scriptural tropes.

In many ways it expresses views now taken almost for granted. For example, the moral relativism of modern atheism is foreshadowed here: morals are not universal but determined by cultural circumstances, and Western concepts of ‘good and bad’ are not intrinsically superior to those of other cultures. This is a view first spoken by Nietzsche’s messiah of atheism: Zarathustra, after having “seen many lands and many people… discovered that much which seemed good to one people was reprehensible and disgraceful to another” (Zarathustra, p.85). Rather than decrying this relativism, the Übermensch makes peace with, accepts, indeed, embraces and even celebrates the idea that man “first implanted values into things to maintain himself” (p.85).

Nietzsche explored the ideas in prose form in his subsequent books Beyond Good and Evil (1886) and The Genealogy of Morals (1887). But what makes Zarathustra a masterpiece is its poetic form. And Nietzsche’s ability to express himself in ways that depart from his caricature image in popular culture make him seem less doctrinaire. He even declared that he might reconsider his position regarding the existence of the Lord if only the Almighty had moves: “I would… believe in a God who knew how to dance” (p.58).

Salomé, Paul Rée & Nietzsche have a night on the town

The Twilight of Nietzsche

“What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” is one of the last lines published by Nietzsche – an adage he arguably immediately disproved. In 1890, he suffered a mental and physical collapse. He had just written Twilight of the Idols or How to Philosophize with a Hammer (its German title, Götzen-Dämmerung, was a pun on, and dig at, Richard Wagner’s opera Götterdämmerung – The Twilight of the Gods). But Nietzsche was unable to enjoy the success of the book. His downfall occurred just as he was on the threshold of fame.

The story often told is that in 1890 in Turin Nietzsche ran out into the street and hugged a horse that was being flogged by its owner at the end of Piazza Carlo Alberto. He then collapsed in and never fully recovered. After the initial crisis, he was nursed by his mother Franziska, and after her death in 1897, by his sister Elisabeth Föster-Nietzsche.

His friends, including the noted historian Jacob Burckhardt, had him transferred to a mental institution. But he was transferred back to the family home, where his sister allowed selected visitors, including the educationalist Rudolf Steiner (who wrote his first book about Nietzsche) to meet the now mute and clinically insane philosopher. At this stage he signed his letters ‘the crucified one’. Later, he called himself ‘Dionysus’. He also declared war against the Pope, and commended Otto von Bismarck to attack Rome to arrest the pontiff. The cause of his illness has been attributed to syphilis that he contracted as a student, but this is controversial and he also suffered psychotic episodes.

After two strokes, in 1898 and 1899, Nietzsche died on 25th August 1900, aged only 55. The ‘Anti-Christ’ was buried in a Christian cemetery – next to his father, the late Lutheran pastor, in his birthplace Röcken, in Saxony-Anhalt.

Restoring Nietzsche’s Reputation

Nietzsche was never close to his sister Elisabeth while he was coherent: he wrote in 1888 that “the treatment I have received from my mother and my sister, up to the present moment, fills me with an inexpressible horror”. Half in jest, he continues that his only “objection to the Eternal Return… is always my mother and my sister” (Ecce Homo, p.6). He didn’t attend his sister’s wedding to a rabid anti-Semite either. For her part, Elisabeth was dismissive of her brother’s rather unconventional relationship with Salomé and Paul Rée. The fact that Salomé was of Jewish descent probably didn’t help. Yet Elisabeth was entrepreneurial. and while Friedrich descended deeper into mental illness, she organised for the first edition of his collected works to be published.

Elisabeth then heavily edited her brother’s many unpublished writings before bringing them to press as The Will to Power (tellingly, Hitler attended Elisabeth’s funeral in 1935). This was a gross misrepresentation of everything Nietzsche stood for. Certainly, The Will to Power, does contain sentences like, “the will to power is the primitive form of affect and all other affects are only developments of it” (p.1067). Taken out of context, such views can be abused by revolutionaries – and they were. This is tragic, since Nietzsche had distain for revolutionary theories all his life. Indeed, earlier in his career he wrote against those who “hotly and eloquently demand the overthrow of all orders in the belief that the proudest temple of fair humanity would then immediately arise on its own” (Human, All Too Human, p.463, 1878). He was not a revolutionary, nor did he expressed anti-Semitic views, let alone nationalist ones. In fact, unlike his denunciation of Christianity, he had a positive view of the Jews:

“What does Europe owe to the Jews? – Many things… the most attractive, ensnaring, and exquisite element in those iridescences and allurements to life, in the aftersheen of which the sky of our European culture, its evening sky, now glows – perhaps glows out. For this, we artists among the spectators and philosophers, are grateful to the Jews.”

(Beyond Good and Evil, p.250)

Nietzsche partly owed his fame to a Jewish academic, the Danish literary critic Georg Brandes, who corresponded with the philosopher and gave lectures on his philosophy at the University of Copenhagen even before Zarathustra was published.

Nietzsche was also anything but a nationalist. Upon moving to Basel in Switzerland he renounced his Prussian citizenship, and remained formally stateless for the rest of his life. His view of the Germans was uncompromising. He – one of the greatest stylists of the Teutonic tongue – believed he was “a stranger to everything that is German”… to “get free from [this] unendurable pressure one needs marijuana” (Ecce Homo, p.29). Whether he was a stoner or not, he lampooned nationalism, which he described as “a plunge and relapse into old loves and narrow views”, while describing himself as a ‘good European’ (Beyond Good and Evil, p.241). In any case, such mundane political matters are not contained in Zarathustra. Here the much reviled ‘will to power’ (Wille zur Macht) idea is not a political statement but a philosophical one: Zarathustra found that everyone’s ‘will to power’ is exemplified in the desire “to create a world before which we can kneel”. But this metaphysical order does not exist, for life is, “that which must be overcome itself over and over again” (p.166). Indeed, if there is a political message in Zarathustra, it’s one that’s almost anarchistic, and anything but supportive of a totalitarian state: “The state is the coldest of all cold monsters. The lie comes out of its mouth, ‘I, the state, is the people’” (Zarathustra, p.69).

Nietzsche’s philosophy in Zarathustra is not predominately concerned with the death of the deity, naked power, moral relativism, or even the ‘Eternal Return’, but a joyous affirmation of living life to its full in a world without objective meaning. The Übermensch – in Nietzsche’s poetic turn of phrase – will jubilantly defy pessimism in a future “where all the time seems… a blissful mockery of moments” (Zarathustra, p.289).

Nietzsche was a dancer. Of course he was! And it showed: “Wasted is every day when we have not danced at least once” (p.228). So, rejoice, despite the emptiness of the literally godforsaken world: “lift up your hearts… and do not forget your legs… For better to dance clumsily than to walk lamely” (p.429). Thus spoke Zarathustra – a man whom Nietzsche described as “the laughing prophet” and “one who loves jumping and escapades.” (p.429).

© Hilarius Bogbinder 2026

Hilarius Bogbinder is a Danish-born translator and writer who studied theology and politics at Oxford University.