Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Moral Relativism Is Unintelligible

Julien Beillard argues that it makes no sense to say that morality is relatively true.

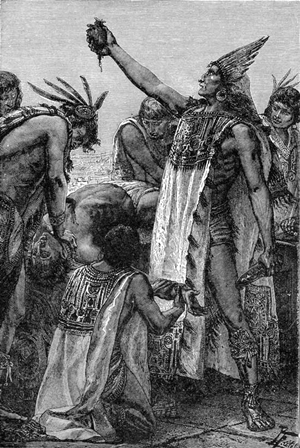

The diversity of beliefs and ways of life is a striking fact about our species. What Mormons find right and reasonable may be abhorrent to Marxists or Maoris. The Aztecs practiced human sacrifice for reasons we find totally unconvincing, and no doubt future people may be similarly perplexed or repulsed by some of our practices. For such reasons, some conclude that there is no objective truth about morality. They say moral disagreement is best explained by the idea that there are many different and incompatible relative moral truths, which are in some way determined by the beliefs of a given society; and that this is the only kind of moral truth there is. So for the Aztecs it was true that human sacrifice is morally permissible, although it is false for us. Generally then, a moral statement M is relatively true provided that it is believed by the members of a society S. (The same basic idea may be developed somewhat differently. Some relativists may say, for example, that M is relatively true provided it is implied by the standards of S, regardless of whether members of S actually believe it. I will ignore these details because they make no difference to the point I’m going to make.)

Aztecs performing a human sacrifice

In this article I will discuss this argument from moral disagreement and present what I think is the most serious problem for moral relativism: that we cannot understand what it could mean for moral truths to be relative. And since we have no idea what it could mean, moral relativism cannot be a good explanation of the fact of deep and enduring moral disagreement – nor can moral relativism be supported by any other kind of reasoning. So if moral disagreement is evidence against the objectivity of moral truth, it can only be evidence for moral nihilism: the idea that there are no moral truths.

Self-Defeat?

The argument for moral relativism from moral diversity is not especially convincing as it stands. If the mere fact that people or groups disagree over some idea were enough to show that that idea has no objective truth value, there would be no objective truth about the age of the universe or the causes of autism. Hoping to ward off that counter-argument, relativists usually claim that these other disagreements are unlike moral disagreements in some relevant way. For instance, writing in this magazine (in Issue 82), Jesse Prinz claimed that scientific disagreements can be settled by better observations or measurements, and that when presented with the same body of evidence or reasons, scientists come to agree, but the same cannot be said of thinkers operating with different moral codes.

Even if we grant this distinction, however, it is still doubtful that moral disagreement is a good reason for accepting moral relativism. After all, there is deep and apparently irresolvable disagreements in philosophy as well as morality. For instance, some philosophers think mental states such as pain or desire are just physical states; others deny this, and yet both camps are familiar with the evidence and reasons taken to support the opposing point of view. Should we say, then, that there is no objective truth about how mental states are related to the physical world? That seems deeply implausible. For that matter, many philosophers deny the moral relativist’s claim that moral truth is relative to what a given society believes. Does it follow that there is only relative truth and no objective truth about moral relativism itself – that moral relativism is true relative to the outlook of Jesse Prinz, say, and anti-relativism no less true relative to mine?

I suspect that few moral relativists would be willing to accept this ‘higher’ kind of relativism. They think that even though many benighted philosophers disagree with them, moral truth just is relative to a given society – that it is an objective fact about reality that there are no objective moral facts but merely relative ones. But this would be a distressingly unstable position, if relativists believe their relativism on the basis of an argument that depends on the principle that if there is a certain kind of disagreement over some topic T, there is no objective truth about T. If that principle is true, the fact that there is such disagreement about their relativist conclusion implies that that conclusion is itself not objectively true, but only relatively so. So if this relativist’s argument is good, then by his own standards he should not believe its conclusion is objectively true; or if he is entitled to believe its conclusion, it follows that the argument is not good.

Need it be self-defeating to hold that moral truth is relative, and that that truth about moral truth is itself merely relatively true too? Happily, we do not need to consider this question with much care, since I think the core problem with moral relativism is not that it is false, implausible or self-defeating, but simply that it is unintelligible. I mean by this that there is no intelligible concept of truth that can be used to frame the thesis that moral truth is relative to the standards or beliefs of a given society.

Truth & Belief

Let me try to clarify this objection by introducing some truisms about truth. First, a statement is true only if it represents things as they really are. The statement that I’m wearing blue socks is true only if I really am wearing socks, and they really are blue.

The same general principle surely holds for moral statements. Suppose I say that suicide is immoral, yet that in objective reality there is no such thing as moral wrongness. That is, suppose that nothing that anyone does really is morally wrong, although some actions seem wrong to us. Then my assertion of immorality is simply false, for it attributes to certain acts a property that nothing has. It is like an assertion that my socks were made by Santa’s niece. Nothing has the property of being made by Santa’s neice, and any statement that represents my socks as having it is therefore false.

Those attracted to moral relativism might object that I am simply presupposing an objectivist concept of truth: a concept that relates what is said or thought about the world to the way that the world really is, independent of these thoughts. What they have in mind instead is a different concept of truth – one that does not involve any such relation between subjective points of view or representations and something independent of those points of view.

I admit that I am presupposing an objectivist conception of truth, but what’s the alternative? Do we have any concept of truth that does not involve that kind of relation? To be sure, people sometimes say that a statement is true for one person but not another – meaning that the statement seemstrue to the first person but does not seem true to the second. But just as seeming gold is not a kind of gold, seeming truth is not a kind of truth. What is meant by this way of speaking (if anything), is simply belief. To say that it is true for some children that Santa Claus lives in the North Pole, if that means merely that to some children it seems true that he does, is really just a way of saying that they believe it. But believing doesn’t make it so. Similarly, if moral relativism is just the claim that what seems true of morality to some people (what they believe about morality) seems false to others, this is true but philosophically trivial, and consistent with objectivism about moral truth. It is also worth noting that, interpreted in this trivial way, moral relativism could not be supported by the argument from disagreement. The gist of that argument was that moral relativism is a good explanation of the moral disagreements we observe. Yet the claim that some moral statements seem true to some people and false to others merely restates the fact of moral disagreement that is supposedly explained by relativism, it cannot explain that fact. (Perhaps some things are self-explanatory, but not moral disagreement!)

So there is the familiar kind of truth dependent on how reality is apart from people’s beliefs or perceptions, and a bogus kind that is nothing more than belief. The relativist’s theory of moral truth explicitly denies that moral statements are ever true (or false) in the familiar sense; but if it is interpreted in the second way, relativism collapses into absurdity or triviality. The relativist needs a third kind of truth, midway between the familiar and the bogus: not just an appearance of truth, but not a truth that depends on objective reality. But there is no such thing. At least, I am unable to imagine what this special kind of truth would be, and relativists are strangely silent on this core issue.

No Third Way

Remember that moral relativism has two ingredients: there is the denial of any objective moral truth, and the assertion of some other kind of moral truth. Suppose that moral disagreement does raise doubts about the objective truth of any moral code. Does it follow that moral codes are true in some other sense? No, for perhaps it means that no moral statements are true in any sense. Perhaps people disagree here because they have been acculturated in different moral cultures, but all the moral beliefs or standards of all cultures are simply false. So the argument from disagreement might be an argument for moral nihilism rather than for moral relativism.

How do relativists hope to establish their positive thesis, that moral statements are sometimes true without being objectively true? I am not aware of any compelling arguments for that idea. On the contrary, relativists tend instead to argue in great detail for the negative thesis, that morality is not objectively true, as if that alone were sufficient for their relativistic conclusion. Thus Prinz says that “moral judgments are based on emotions”, that “reason cannot tell us which values to adopt”, and that even if there is such a thing as human nature, that would be of no use, since the mere fact that we have a certain nature leaves it an open question whether what is natural is morally good. Let us grant all of this, and grant for the sake of argument that it does raise a real doubt about the objective truth of moral beliefs. In the absence of any account of the special kind of truth that is supposed to lie somewhere between mere belief and accurate representation of objective reality, why then should we think of moral judgments as truths of any kind? Why not simply say that all moral codes are false? It would seem reasonable for a philosopher who thinks of moral reasoning in this way to view moral beliefs in the same way that atheists view religious ones – as false.

I suspect the reason few philosophers have been willing to draw this nihilistic conclusion is simply that, like most people, they have some strongly-held moral beliefs of their own. They think that it is morally wrong to rape children, for example, and so they do not want to say that that belief is false. For how could they continue to believe it, while also believing that what they believe is not true? This unhappy compromise is not tenable. If there is no objective moral truth, there can’t be some other kind of moral truth.

© Julien Beillard 2013

Julien Beillard teaches philosophy at Ryerson University, Ontario.