Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Philosophical Counseling

Maria daVenza Tillmanns on understanding self and others through dialogue.

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used to create them.” – Albert Einstein

The philosophical counseling movement started during the early Eighties in Europe and the US. It seemed to be a zeitgeist phenomenon: the time was ripe, and a number of people around the world who had a strong interest in philosophy ‘suddenly’ had the brain wave, why not apply philosophy to everyday life? Some present-day philosophical counselors recount how they wanted to study philosophy precisely for its merits with respect to everyday life, and how disappointed they were to find out that academic philosophy seemed to have stripped philosophy of its application to lived reality. Academic philosophy seemed to be only that – academic. Where did the philosophy of Socrates go – the philosophy of the market place? The idea behind the philosophical counseling movement was to rescue philosophy from the ivory tower and let her live in the world of the everyday.

Philosophical counseling is somewhat more established in Europe and Israel than in the US. Dr Gerd Achenbach in Germany is said to have started what has become the movement of Philosophical Counseling. Shortly after, Adriaan Hoogendijk in the Netherlands picked it up. Hoogendijk received a lot of publicity across Europe. Achenbach’s idea came out of the ‘anti-psychiatry’ movement, whose core notion was that it is not enough to listen to people for the sole purpose of discovering symptoms. This may be too narrow an approach by itself, and fails to do justice to a person’s story. In contrast, philosophical counselors are interested in people’s stories in order to get a better idea of the bigger picture. Perhaps the bigger picture points to life dilemmas around values, loyalties, trust, etc and does not only indicate psychological traumas.

On a sliding scale of counseling professions, one may think of psychotherapy as dealing predominantly with a person’s psychological and emotive make-up, R.E.T. (Rational Emotive Therapy) as combining the rational and emotive aspects of a person, and philosophical counseling as focusing predominantly on the rational by concentrating on people’s worldviews – their conceptual understanding of the world. Right now there are probably as many interpretations of philosophical counseling as there are philosophical counselors. Over the years, I have been developing my own theory of philosophical counseling. I personally do not understand philosophical counseling to be mainly focused on the rational. To me, it seems that life is inherently problematic, and cannot be reduced to a set of isolated problems (whether psychological, emotional, or rational) which need to be solved and overcome in order to live life more successfully. I’m not ready to throw the baby out with the bathwater and discount everything other counseling professions have achieved in helping people and relieving their suffering; but life can never be problem-free, and was never meant to be. Life is not meant to be solved; it is meant to be lived! Philosophical counseling, therefore, should approach a person’s life as a whole and not as a series of individual problems. For the philosophical counselor, the emphasis should be on life as lived rather than on the self’s problems. Moreover, to look at philosophical counseling as I do, from a dialogical perspective, as understood by Martin Buber (in I and Thou, 1923, for instance) is to focus on the interaction between people rather than concentrating on what happens solely within a person (psychologically, emotionally or rationally).

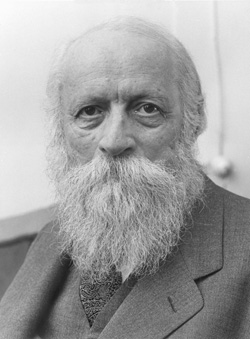

Martin Buber (1878-1965)

We think we live in the same world, but that’s hardly true. We live in a multiverse in which we are so different from one another that it often seems a miracle that we can understand each other at all. For Buber the only way to come to an understanding of the other is through dialogue, not through already-existing thought structures steeped in our experience. Buber refers to this as viewing someone as “content of my experience” instead of as “other”.

Hermeneutics, which is the art or science of understanding, developed quite separately and differently in Germany and the Netherlands, the countries where philosophical counseling took off. German hermeneutics originated in Lutheran theology, which was focused on understanding fixed texts, essentially Bible texts, through the experiencing subject. In Holland, however, a different kind of hermeneutics developed, out of the Socratic tradition. Roughly speaking, one could postulate that the German tradition led later to the concept that in order to gain a deeper understanding of the world we need to overcome the alienation caused by the limits of our contexts or ‘horizons’ as so-called ‘fixed texts’. The Dutch tradition, on the other hand, led to the concept of becoming familiar with a forever-changing world. This approach implied that our contexts were not quite as fixed as the Germans imagined them to be; and since horizons are perpetually changing, we need not make our understanding of the world and others conditional on overcoming them. It is this second way of coming to understand, which I have taken up in philosophical counseling, and for which I have found a solid basis in Buber.

Buber’s notion of the other (person) is diametrically opposed to the postmodern notion of other. In postmodernism, ‘otherness’ refers to that which has been exiled and excluded from the I; it refers to that which is the denial of ‘I’. For Buber, the ‘other’ simply refers to that which is ‘not-I’. The difference lies in the fact that Buber’s notion of the ‘not-I’ (or ‘Thou’) is rooted in trust, whereas the postmodern notion is rooted in distrust. With the widespread collapse of belief in modernity and its grand narratives of progress, distrust prevailed, and the notion of ‘otherness’ was contaminated by distrust. In contrast, Buber’s notion of the dialogical implies acknowledging the other’s otherness, not trying to overcome it. Buber emphasizes the need to enter into dialogue with the other, for in the process of engaging the other we can meet him or her in the “between.” We need not try to understand the other’s context prior to interacting with them. That would, in fact, be an act of distrust.

So Buber’s notion of the ‘not-I’ maintains trust. Trust means accepting the claim the other has on me (the ‘I’) and responding to that claim. For Buber, this notion of having a claim on each other is the basis for human interaction. Here, a ‘claim’ does not refer to a sense of demand or expectation that one has to live up to; it refers to a response because of our humanity. It’s important to realize that a claim in this sense is something that can only be understood implicitly. For an analogy, take the messages of oracles, which are scrambled, and on face value incoherent. Their meaning lies beyond rational analysis. They can only be understood implicitly. Importantly, how the message will be understood and interpreted is dependent on the uniqueness of the listener, and on the interaction between the message and the listener. Trust based solely on what is proved to be true is not true trust. In that case, instead of a person’s own commitment and decision to take it upon herself to trust, and to engage herself in building a trust relationship, proof becomes the basis for trust. But you cannot make trust conditional on categories of thought that have to deliver ‘proof’.

Trust is established on the basis of what is implicitly understood by two people. It’s a two-way knowing. To distrust the other, however, means to distrust the claim the other has on you. Distrust distrusts the gap between self and other. So it robs one of the distance necessary for any true relating to take place (Buber). It also uses rationality as a means to bridge the gap. Rationally, one tries to make sense of the other, so that one can now safely trust him: I trust him because… Here, instead of struggling to establish trust as a result of dialogue, we appeal to rationality to establish it for us. But life cannot be reduced to what can be rationally understood. Reason and rationality are of great importance in our lives, but they cannot be used to bridge the void between people.

This is where phronesis (which in Ancient Greek means understanding, and also deciding) comes into play. Phronesis is being able to implicitly understand the meaning and claim a certain message coming from another person may have. These messages have no single meaning which may be rationally understood by everyone, and instead rely on personal response.

Buber’s method flies in the face of much psychology and sociology, which stress the importance of developing structures for understanding. Philosophy, on the other hand, develops structures of understanding (which are themselves constantly subject to change) as a result of engagement. For Buber also, the emphasis is on engaging life directly, rather than trying to interpret life through fixed categories of thought. Therefore, the approach to philosophical counseling he inspires is in complete contrast to psychiatric counseling, where counselors will assess their clients through relatively fixed structures of thought, such as the diagnostic system of DSM IV (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, the main reference work for the classification of psychiatric disorders). Philosophical counselors are more interested in the whole story as a story, as an eyewitness account of life: what does this person’s account tell us about life?

The difference between Buber’s approach to the other and the postmodern approach is of great importance to fields like counseling. Counseling cannot exist without trust as the basis for the counseling to occur in the first place. It is the trust to engage the other, without knowing them first on the basis of what we can know about them through a pre-extant system of thought. In counseling, it is important to be able to acknowledge the other as other, and to be able to ‘meet’ the other while holding one’s own ground (terms Buber uses to describe the dialogical). Yet one can only do so when one can trust the other’s otherness through implicitly understanding his otherness. Otherness in Buber’s terms is not something we can know explicitly. I believe this is why much of our research in the fields of counseling and education has gone astray: the need to make explicit creates the need for categorizing people. It creates an I-It relation, and in the process the true nature of their otherness is sacrificed, because the other person is not a fixed thing to be categorized. For Buber, to know the other person explicitly is to objectify them. Otherness cannot be classified or categorized without sacrificing otherness in the process.

Buber argues that the other can only be understood through the I-Thou relationship. We need to learn how to engage the other directly through trust, and understanding will develop out of this engagement. Understanding cannot be achieved through developing ever-more sophisticated categories of thought by which to categorise people. Yet that’s precisely what we are doing when we categorize people in terms of gender, ethnicity, language or culture. These categories are facts of life, but they cannot be all that we can say about life. In fact, we have to swing back and forth between the I-It and I-Thou (Buber). We need both the skills of knowing explicitly (I-It) and understanding implicitly (I-Thou).

In the Western world, in which reason has dominated, it is important to restore the element of trust towards others. It is also important to view the gap between self and other as the distance needed for relating, and not as a void which needs to be bridged. Philosophy as an art (and not as an ivory tower discipline), can help us restore the trust Buber talks about, by virtue of the fact that it engages with the world, but not through preconceived categories of thought (which is also a weakness of ivory tower philosophy).

Philosophical counseling tries to set free thought that’s otherwise trapped in its own fabrications. Like all philosophy, it questions taken-for-granted assumptions – presuppositions about life, beliefs and values, both as uniquely our own and as part of the world in which we live. In this way philosophical counseling can come as a breath of fresh air, and can be very useful to people within the context of their home and work life. It depends above all on the desire to be reflective, to become mindful of one’s thoughts and actions and mindful of life in general. To live one’s life as an answer is to accept one’s life’s circumstances. But the foundations of philosophical counseling are the idea of living one’s life as a question, not an answer. To live one’s life fully means to live in open response to life as we both encounter it and create it.

© Dr Maria daVenza Tillmanns 2013

Maria daVenza Tillmanns is a former President of the American Society for Philosophy, Counseling and Psychotherapy (ASPCP), and currently teaches philosophy peripatetically in California, including as the Philosopher-in-Residence at La Jolla Country Day School.

• This topic was considered in a different form in the IJPP, the on-line journal of the ASPCP (now the National Philosophical Counseling Association).

Case Study

Mrs S., a retired M.D. who specialized in asthma and who was very well respected in her field, came to visit my private practice in Holland after she had attended one of my presentations on philosophical counseling, where she made an appointment to see me.

Before Mrs S. retired, her time was pretty much organized around her private life on the one hand and her professional role on the other. She would wear her two hats alternatively, depending on whether she was in the office or at home. Yet, now that she was retired, it was no longer clear to her when and how to wear her separate hats. Her life, which had seemed so well organized, was suddenly in disarray, and she felt lost. She also mentioned that she was having the same dream repeatedly. In the dream there was a closet which, once she opened it, she could no longer close, because it was such a mess and everything kept falling out.

We philosophized on the meaning this dream could have for her, playing around with a number of different interpretations, and we concluded that her strictly scientific worldview had made it very difficult for her to deal with her present chaotic reality. She was used to fixing things in other peoples’ lives, and was now left feeling quite powerless trying to fix things in her own life. This is what we thought her dream seemed to imply.

After a few weeks she reported that she wasn’t having the dream anymore. She was quite relieved, because the dream had made her quite anxious.

At some point, Mrs S. told me about her sister’s meaningless suicide, and how she could never forgive her sister for the grief this had caused their parents. At this point I suddenly shifted from being understanding to almost accusing my client of not recognizing her sister’s pain and screams for help. My client was shocked. However, later she told me how grateful she was to me for “waking her up.”

As I interpret these events from a dialogical perspective, I see I had succeeded in shaking some meaning into a world which had appeared meaningless to her. She had glimpsed the otherness of the world of the ‘meaningless’ other – enough to know that it too existed, and had a unique meaning of its own. Through ‘imagining the real’ (Buber), I tried to imagine her sister’s suicide. Through the dialogical relationship I had with my client, I tried to convey to her the sister’s position as I had ‘imagined’ it. My client, who was able to hear me, was now also able to hear her sister for the first time through me. She moved from being caught in an I-It understanding of her sister’s suicide, to one in which her sister had again become a Thou. The sister’s scream was finally heard. As a result, the suicide no longer appeared meaningless, for it had not been meaningless for her sister. Their realities were incompatible and incommunicable, yet through entering into an I-Thou relation with her sister, my client was now also able to ‘imagine the real’, and so ‘meet’ her sister for the first time.

Shortly after, we terminated the sessions.

Maria daVenza Tillmanns