Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Theatre

Socrates and His Clouds

Katie Javanaud sees a dramatic vindication of Socrates.

In philosophy professor William Lyons’ new play, Socrates and His Clouds, recently premiered in London by The Meddlers’ Theatre Company, Socrates, finally, is vindicated!

Lyons’ drama is loosely based on Aristophanes’ ancient play The Clouds, written in 423BC. In this comedy, Aristophanes poked fun at Socrates and his school. Plato blamed the play for influencing the outcome of Socrates’ trial decades later. But whereas in Aristophanes’ play the figure of Socrates appears as a buffoon and a sophist (and an extremely pungent one at that), Lyons’ Socrates is a free-thinker encouraging a new trend in the education system, namely to make students self-reliant in their thinking.

The play deals with an array of issues facing the modern world: including the precipice on which morality itself now tilters, the failures of modern educational systems, and the misuse of political power. Described by the author himself as a ‘serio-comic’ drama, the central message of the play is that consideration of what makes for the ‘right’ kind of life, is not something to be ridiculed. In the unfolding of the story a hidden meaning is also revealed: the play is in large part a comment on the current economic crisis in which Greece now finds itself. In this deeper meaning, the play implores us not to turn our back on what is still a vibrant and rich culture, nor to look with indifference upon the sufferings wrought by the irresponsibility of Greece’s creditors.

Strepsiades and Phidippides dispute the merits of philosophy

Photo © Katerina Angelopoulou 2013

The plot revolves primarily around the turbulent relationship between a bricklayer, Strepsiades, and his son, Phidippides – a son who likes to gamble and has a keen taste for horse racing. In a bid to resolve his desperate financial situation, Strepsiades pays a visit to Socrates’ Academy, in the hope that his son will be admitted as a student, enabling him to obtain qualifications, and eventually a highly-paid job, such as a banker. As soon as Strepsiades arrives at the Academy, however, it becomes clear that he has come to the wrong place if he wants a quick-fix cash solution. As the student opening the door tells him immediately: “We’re a loss-making part of the education industry.” And when Strepsiades mistakes her for a servant, she corrects him with “I’m one of the students, trying to pay my way through college, working part-time as the door-person.” So even this door-keeper has a message to communicate: she represents anybody willing to perform mundane tasks for the sake of pursuing something ultimately more satisfying; such as becoming proficient in philosophy. She is an exemplar, prepared to see financial gain as only instrumental to attaining some greater good, rather than as intrinsically valuable or a goal in itself.

To the philosopher Socrates also, money is not all that counts: instead, for him, “the unexamined life is not worth living.” On Strepsiades’ entry into the Academy, the conversation turns almost at once to the source of morality. The question being discussed is this: if morality comes from the gods, how can we be sure that their precepts are being delivered to us accurately? (The dilemma of Plato’s Socratic dialogue Euthyphro is being invoked here.) Historically, it was charges of immorality, disrespecting the gods and corrupting the youth of Athens that resulted in Socrates’ execution. But as Socrates asks Strepsiades, “Maybe it’s only the losers that ever change things?”

The theme of the difficulty of discovering and subsequently following the demands of morality is constant throughout the play. The idea that it is better to rely on reason to discover what is right or wrong rather than rely on a potentially faulty postal service from the gods, is brought to the fore in the debate witnessed by Phidippides at the Academy between Reason and Persuasion. Persuasion argues that ‘the good’ is whatever people decree as good. Reason challenges this by imagining a scenario in which tyrant bankers and accountants assert (satirising the current crisis in the Greek economy) that it is an ‘economic necessity’ to practise euthanasia on those who have become too burdensome for society, such as the elderly and disabled. Surely, Reason asks, this action would not be good simply because those with power deemed it so? This debate, modelled on the one in Aristophanes’ play between Inferior and Superior argument, is perhaps the play’s most engaging and entertaining scene. Although one has the clear impression that Reason is superior in the eyes of the playwright, to Phidippides, Persuasion wins the day, and it is not hard to see why. She, after all, seems better able to offer what a majority of people, ancient and modern, value: power and profit. Socrates questions the ultimate worth of those life objectives, and for that reason is presented favourably by Lyons; but Socrates’ accusers, the disciples of Persuasion, remain as much on the prowl in the twenty-first century AD as they as they were in the fifth century BC.

Behind The Scenes and Between The Lines

Plato’s famous allegory of prisoners in a cave watching only shadows – referring to the distinction between reality and what merely seems real – is particularly well staged. As the narration unfolds and we are told “the only sign of life or movement the prisoners would ever see is the play of shadows on the back wall of the cave…” the lighting adjusts to present the actors on stage against the back wall of the theatre. Suddenly it is us, the audience, who are the prisoners of the cave, confusing the shadows with reality itself. Is there a message here about our relationship to the media?

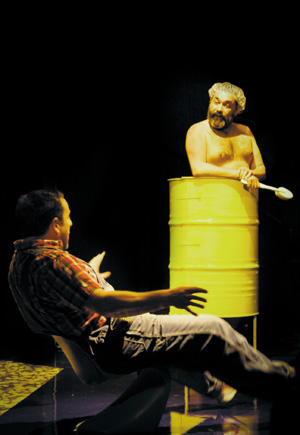

Socrates proving to Strepsiades that philosophy is a barrel of laughs

Photo © Shaun Bedassie 2013

Towards the conclusion of his discourse on the cave, Socrates considers the idea that we live our entire lives as though prisoners of such a cave. On the rare occasions that we do venture into too-bright daylight we quickly find ourselves begging to return to the safety of the illusions the cave brings with it. The allusion applies particularly to the character of Strepsiades, who has been partly enlightened by his conversations with Socrates, yet lacks the courage to progress in his philosophical studies, thinking these musings to be above his station as an old bricklayer.

Socrates’ lecture on the allegory of the cave and the debate he chairs between Reason and Persuasion have the following idea in common: that although the majority of people may consider themselves to be pursuing reality, in fact they are apt to misunderstand the very notion. So they turn away from the authentic life (in Socrates’ eyes, characterised as an examined, ethically upright life) for a life centred on the vain pursuit of wealth, social standing and power. Yet what, asks Phidippides, is the worth of a qualification if it will not provide you with prospects of wealth?

Aristophanes’ Socrates had an intense preoccupation with speculating about the physical world. This is an attribute Lyons does not abandon but transforms into a virtue rather than something to be ridiculed. The walls of his Academy are lined with astronomical and geometrical charts; but Lyons’ Socrates also clearly values poetry, particularly Homer’s description of dawn as ‘rosy-fingered’. Socrates indicates that poetic language is often more revealing than attempts at expression in literal terms as favoured by the politicians and bankers. As he hints, a “rosy-fingered dawn” is certainly more enticing than a sunrise “marked by the accumulation of cirrus clouds… arranged in fan-like striations from a point on the horizon” – but then one will not be as well rewarded for shorter lines, if one is being paid by the word!

Lyons’ thinking may owe something to a famous passage from Orwell’s essay Politics and the English Language (1946) in which a verse from Ecclesiastes is ‘translated’ into a modern political jargon – an early version of Newspeak. Ecclesiastes 9:11, King James Version:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

– translated into “modern English of the worst sort”:

Objective consideration of contemporary phenomena compels the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

Both Lyons and Orwell are making the important point that a language robbed by political ideology of either concreteness or metaphor is not just poorer in expression, but emptier of meaning.

The standard Socratic method of philosophical investigation, validated and extended by his greatest follower, Plato, is of course dialogue, so nothing could be more appropriate than for the ideas of these great ancient philosophers to be presented and scrutinised in a contemporary dramatic production. (Plato himself was a good friend of Aristophanes as well as Socrates, it seems, and it is interesting to note that when the latter two come into contact in Plato’s dialogue The Symposium – set seven years after the first performance of The Clouds – Socrates does not appear to feel any resentment, or Aristophanes any embarrassment.) Another appealing aspect of this play to readers of Philosophy Now will be that it incites its audience to go back to the texts that inform it.

This was an inspiring play, performed and produced by a group of dramatists and technicians who seemed to have been equally inspired. For those with an interest in political philosophy, current affairs, or indeed modern moral philosophy, this is a show well worth looking out for. The coming together of nations is a theme maintained throughout the play and was given compelling expression by the choreography inspired by traditional Persian and Egyptian dance. With original music and dance sequences produced and performed by Greek artists, the play itself demonstrates that Greece still has much to offer, and that Europe should not abandon the nation responsible in large part for its philosophical, literary and wider cultural heritage. Were Europe to forsake Greece on the grounds that it cannot contribute economically, it would be guilty of much the same crime as the Athenians when they renounced Socrates and condemned him: Socrates’ financial contribution amounted to nothing, and he no doubt caused discomfort in his interlocutors. However, his bestowing of true goods upon the people who have encountered him throughout the centuries has persisted even to the present day.

© Katie Javanaud 2013

Katie Javanaud is studying the History of Philosophy at King’s College, London.