Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Play

Consciousness: A Play In One Act

David Dobereiner imagines a meeting of great minds.

Characters:

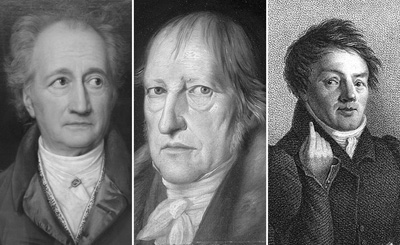

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Poet, playwright, scientist.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Philosopher.

Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner: Chemist.

It is 1829, and we are in the Faculty Club of the University of Jena.

Goethe: Ah Herr Döbereiner! I am pleased to introduce Herr Hegel to you.

Döbereiner: I am honoured to meet you, Herr Hegel. I had not heard that you are lecturing here in Jena?

Hegel: I started my career here, but I am now established in Berlin. I have just come back to Jena to deliver a lecture on consciousness. I am also a protégé and friend of Herr von Goethe, and pleased to see him again. And yourself?

Döbereiner: Oh, I am a Professor of Chemistry here. I have discovered some affinities between certain triplets of chemical elements that I call ‘triads’. I have also discovered a new principle, by which a reaction can be brought about between two chemicals by a third which remains unaffected. And I too am a protégé and friend of Herr von Goethe. So what will you be telling us about consciousness?

Hegel: Well, consciousness is a property of mind, and individual human minds are nothing but tiny reflectors of the radiance of God’s Mind. In that sense all human consciousness is connected to the Creator, and therefore all minds partake of the Absolute Idea. But at our present state of development we are not yet fully conscious of this connection.

Goethe: Hegel, with your ‘Absolute Idea’, you talk as if mind were the only reality. But what kind of a Creator would go to the lengths of constructing a whole universe of materiality if its only purpose was to be transcended, with difficulty, by just one of its creatures? And surely, at the moment that Johann here makes an amazing discovery in his laboratory, through close observation of entirely material properties, he is just as close to the divine as the saint or mystic ever was?

Goethe, Hegel, Döbereiner

Döbereiner: Thank you for that kind comparison. And I should say, you yourself were almost at a point of divine madness when you conceived the idea of basing your novel Elective Affinities on my triads. From chemical to psychological affinities – what brilliance! But it speaks to the fact that the roots of life, and therefore consciousness, must be embedded deep within the physical realm.

Hegel: Yes of course. God must be conceived as both transcending Nature and immanent in Nature. But consciousness itself emerges as a later development in the history of the universe. We are now at that later point. Consciousness’s role in history is now to achieve a higher state, and that is transcendence. Consciousness is of course not a material thing. But it is just as real as your body, and it is something you must acknowledge as being as real, in fact more real, than any phenomenon you experience. Objects presuppose subjects.

Goethe: I disagree. I believe subject and object are two sides of the same coin. We experience ourselves subjectively and the Other as object. But everything down to the smallest atom has some prototypical stirring of intent, which in plant life emerges as sentience, and in animals includes consciousness.

Döbereiner: I am prepared to accept what you say, Goethe – as a working hypothesis. As a scientist I can see no evidence that there is a God, but if there is none such, then I must accept an earthly origin for every phenomenon I experience, however immaterial it appears to be in our present state of knowledge.

Hegel: Are you seriously advising us to reject any guiding force in the progress of civilization? Are you claiming that the lives of Jesus, Socrates and Plato were a result of mere chance – the outcome of a natural process, perhaps? It is through the minds of such great teachers inspired by the workings of the dialectic that we are now on the cusp of understanding the ultimate reality – pure thought!

Goethe: Hegel, I must take issue with you here. I would submit that there is no such thing as pure thought. And if there ever was, it would be as cold as a corpse. The great innovators of pure mathematics – Pythagoras, Descartes, Newton and Leibniz – were all creatures of flesh and blood. Pythagoras’ theorem, Descartes’ coordinate geometry, the calculus of Newton and Leibniz – all these most abstract systems sprang from a problem-solving impulse. They all desired to serve mankind; and the proof of their earnestness is the extent to which we have seen these systems applied, with spectacular success, ever since; and especially since the beginning of our present scientific era.

Döbereiner: And the joy, the surge of visceral delight that surely accompanied the inspired moment of the seeding of their systems must have been as intense as that of the greatest artists conceiving their greatest works.

Hegel: I don’t deny there may well be some emotional by-product of creativity, but it is not of the essence. These mathematicians were indeed inspired. They had stepped up the dialectical ladder of Ideas into the realm of Spirit. There they found their answers already pre-existing, in the Mind of God.

Goethe: How do you know?

Hegel: My dear friend, how could it be otherwise? Look at the whole sweep of human history, and the natural history that prepared the ground for it. This progress, beset by set-backs such as the French Revolution, nevertheless persists. Can it all be meaningless?

Goethe: But if we are to search for meaning scientifically, we must only accept an explanation if there are good reasons for doing so. Hegel, you posit a higher realm of Spirit which is eternal and unchanging, and to which we humans all aspire, albeit fitfully and with many backslidings. I see no evidence for this theory in the natural world – of which the mind of man forms only one part, and not necessarily the most significant part.

Hegel: Can you give a more plausible accounting for progress?

Goethe: I am going to shock you. So be prepared.

The other two smile wryly.

Goethe: All mere theory, dear friends, is gray; but the golden tree of life springs ever green, and love and desire are the spirit’s wings to great deeds! Authentic romantic love is the highest point in our life-experience! And only when lovers consummate their love do human beings truly experience the divine. In your terms, Hegel, this encounter of ‘thesis and antithesis’ may achieve its sublation in the form of a baby human – a synthesis that combines within itself elements of both its parents, but is, at the same time, something completely new. This is the archetype of your dialectic. And prior to the mind is the body, just as prior to thought is feeling. And prior to the human animal are other animals – who behave in emotionally similar ways.

Döbereiner: I can take this theory a few steps further back if I may. Prior to the organism is the organelle. Prior to the organelle is the complex molecule. Prior to the molecule is the atom. We scientists have not yet finished even here. Before this century is over, we may even have discovered the structure of the atom. Then that will be prior.

Hegel: You two talk as if everything in the universe somehow developed out of primordial matter. How could that possibly be? What is God’s role in all this?

Goethe: Perhaps God is a female and is in process of giving birth to ever improved versions of Herself.

Hegel: I have never heard such nonsense!

Goethe: Perhaps because you haven’t studied ancient Chinese texts, tablets from ancient Sumer, or taken seriously Pythagoras’s beliefs. Do you dismiss St Francis as an aberration? All these sources – and, I am sure, many more – lend credence to that view. Your trouble is that in your efforts to construct a comprehensive system, even before putting Western philosophy and history under a microscope, you have said to yourself that everything that happened here in our Western world must have been a result of God’s Will. Then you have built your system up around this prejudice, and generalized it to embrace the whole universe!

Hegel: Don’t you believe in God, von Goethe?

Goethe: Certainly not in One who stands serenely outside His creation and determines the course of history like Napoleon at the battle here.

Hegel: I am in agreement with you there. God works from within our minds, which are but fragments of His Mind. Through reason, operating by dialectical laws, civilization makes its way forward, or rather, upwards. We are free, but only within the limits of God’s law, which manifests itself in the State. In a state of nature we are slaves to our passions. Even Rousseau came around to seeing that. We need strong states under enlightened leaders. Only then are we truly free. And wars between states are sometimes necessary to extend the realm of the most advanced civilizations. Think of human progress under the Pax Romana.

Döbereiner: What? Your State idolatry will spawn a future of many new Napoleons rampaging over Europe, and it barely survived the original! But at least we are clear now. Hegel says make war. Goethe says make love. If I had to choose, I would say make love, not war.

Goethe: But that is a false dichotomy. There is a universal polarity of attraction and repulsion present in all things; in life, and even in inert matter. Also present is a third impulse, which I call ‘intensification’. This is the urge to combine, complexify, to grow – if you like, to transcend. And as beings of higher consciousness, including conscience, we know what we must do in relation to other living beings. We must not harm them even if we find them repulsive. We must affirm ordinary life and personal love. But we must also work to improve the lives of our fellow beings, and this is what I call ‘social love’.

Hegel: But this is straight from the New Testament. If you accept that, you must also see the truth of the Holy Trinity: that Father, Son and Holy Ghost is thesis, antithesis negating it, giving rise to the synthesis through sublation, which negates the negation. This shows that the divine must assume a dialectical form. Just as the triangle is the strongest and most stable of forms in Nature, so it is in the Supernatural.

Döbereiner: Hegel, you have completely lost me here. This is all speculation. You have taken Goethe’s theory, which for all its outlandishness is based on observation of the physical world, and have tried to force it into a mould derived from the dubious revelations of pre-scientific authors combined with your own thoughts about the thinking process. Next you will be recruiting my triads to join your dialectical host. And Goethe has given you another triangle to play with in any case: attraction, repulsion, and intensification.

Goethe: But the universally-acknowledged giant intellect of Professor Hegel is not playing games. Far from it. His discovery of the fundamental law of thought assures his enduring fame regardless of its applications. But concerning thought, I would like to get back to our original topic, to what degree consciousness transcends the personal. It is true that when we look at nature we never see anything isolated, but everything in connection with something else before it, beside it, under it and over it. And what I am conscious of at any given moment is only a tiny part of what I know. But doubt grows with knowledge. Furthermore, all things are only transitory.

Hegel: Hah, Goethe, now you are beginning to sound a little like that misanthrope Schopenhauer – who, by the way, has tried to lure away my students into his web of gloom by lecturing at the same time as myself. Needless to say he has failed.

Döbereiner: Herr Hegel, neither your optimism nor Schopenhauer’s pessimism have any place in the objective search for truth. We must take nature as she is and try to analyse her secrets step by step. When experiment discloses an unexpected reaction, we need to repeat it many times under different conditions. Only then are we entitled to form a rational hypothesis about what has happened. This is just common sense.

Goethe: But Herr Döbereiner, objective truth is not the only truth. There are also the subjective truths which we recognize in the beauties of nature and art. Every day we should hear at least one little song, read one good poem, see one exquisite picture, and, if possible, speak a few sensible words. Perhaps therefore we should accordingly say there are different phases of consciousness? The emotional is one, and the intellectual another.

Hegel: Well, the surge of feeling that forces itself into our consciousness arises from our bodies and is animalistic. As such it may be good or bad. That is for our consciences to decide. Our rational selves alone can know whether a particular appetite is compatible with the social structures that surround us and unite us with our fellows. But although we are in a sense split in our consciousness, the dividing line between the two halves should be considered as running horizontal, not vertical. The higher self is the rational, the lower self the emotional.

Döbereiner: You place the rational self above the emotional, but you say nothing about the rationality of the social structures to which our conscience must attend, and to which we must make our emotional reactions compatible. Do the laws and customs of any society inevitably embody what is best for the citizens they regulate? I don’t think so.

Goethe: As a member of the aristocracy I am immensely privileged. When I wake up in the morning I can decide to do anything I like. If anything onerous needs to be done, I can easily command a servant to do it. The prevailing social structure provides me with total freedom and my servant with very little, since he must hold himself in constant readiness to attend to my orders. This obviously is far from an ideal social order. Nevertheless, I suspect any alternative would likely be even worse – and I am not eager to be led off to the guillotine. So my conscience teaches me that in order to make the status quo humane, I must take it upon myself to consider the welfare of my personal servants and the villagers who also serve me. I will always help them and save them from troubles, if I can.

Hegel: Patronising them all the while.

Döbereiner: But von Goethe is a Patron. Even of you and me. Who got us our jobs here?

Goethe: Well in your cases I was just an intermediary. I am a friend of the Duke. It is an operation of what the English call ‘the old boy network’. But in both your cases, the brilliance of your lectures and publications subsequently vindicated our decision to hire you.

Hegel: Thank you, Goethe. But now let me step back and try to analyse our differences over the nature of consciousness. You both seem to see consciousness like the flowering of an organism with deep roots in the material world, and therefore present in the material world outside the human realm.

Döbereiner: You are right Professor Hegel, to a certain extent. Indeed the degree of convergence in our thinking is remarkable considering our radically different starting points. But there are differences. Goethe and I both want the betterment of mankind, but I am from a humble background and approach my work as a scientist from a utilitarian perspective. Goethe is at heart a romantic and a poet. He sees the world from the perspective of art, as I do from science.

Goethe: (smiling) That is a little sweeping, but let us not quibble. It seems that art and science are united in seeing consciousness as emerging out of the material world. It is now for philosophy to demonstrate exactly why we must both be wrong!

Hegel: I accept the challenge. My answer has already been prepared for me by my predecessor, Kant. He acknowledged – as indeed did Aristotle – that animals show they must have a measure of practical reason. Therefore, they must have minds of a sort, and so consciousness, of a sort. What they clearly don’t have is pure reason, nor any sense of the morality that comes from it. They can judge what may be more or less advantageous for them, certainly, but not what is right or wrong. They have no conscience. The higher form of consciousness, capable of abstract thought and moral judgment, is found in only one place under the sun, and that is in the mind of man. Here only do we find true Consciousness.

Goethe: Hegel, you have raised your standard high and clear, so now it is easy for me to aim my cannon! Birds, beasts and bees all, like human beings, must bring their offspring into the world and care for them, until they grow to replace their parents. In the process they all, like us, must make their peace with their neighbours in order to secure a private space within their tribe. This is their morality, and ours.

Döbereiner: But this is just instinct. They are not acting morally. They don’t have any choice about it.

Hegel: Exactly.

Goethe: I have not finished. You have just raised the issue of free will, Herr Döbereiner. You seem to take the common position that human behaviour is uniquely self-prescribed, but that of other animals is determined by something we label ‘instinct’. We nail these labels onto human and animal to reinforce our prejudice that we are completely and utterly different, but this cannot be so. Anyone who has an emotional tie with an animal knows that they differ in personality one from another, just as humans do. If they were only automatons, as Descartes theorised, they would all behave the same way. There is a much simpler and more satisfying explanation of why they appear so much like us – loving, hating creatures, behaving sometimes rationally, sometimes spitefully, but always with the appearance of self-control. They are like us. And we are like them. Moreover, I predict that before many years have passed some scientific genius will prove a natural law that connects the species and shows how they grew one out of another, culminating in human beings. But the human race is a monotonous affair. Most people spend the greatest part of their time working in order to live. Until science can provide the means for us to re-integrate working and living and make both pleasurable and fulfilling, we will not have progressed beyond the wild ones. This is what I am being told by my consciousness.

© David Dobereiner 2014

David Dobereiner is a distant relative of the famous chemist. He is an architect, and is the author of The End of the Street: Sustainable Growth within Natural Limits (Black Rose Books, 2006).