Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Being Charitable To Kant

Terri Murray tries to be so.

Immanuel Kant’s ethics is haunted by the unfortunate impression that the man himself was a humourless dogmatist so hung up on one doing one’s duty that he lacked all common sense. This unfortunate reputation springs from the fact that Kant admitted no exceptions to certain rules that he thought everyone should obey, but which turn out to be problematic. Can Kant’s ethics be salvaged?

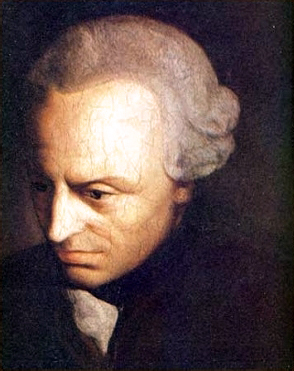

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) – Humourless dogmatist?

For Kant, justice towards individuals was to be sought in the universal and impartial character of what he called ‘the categorical imperative’: “act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it becomes a universal law” (The Groundwork For The Metaphysics of Morals, 1785). Acting contrary to the duties that this imperative implies is wrong, no matter the consequences, and no matter that it may conflict with my own preferences or loyalties. Making exceptions in favour of ourselves or our loved ones is ruled out as a matter of logic. If something is morally good, it is morally good for everyone in the same circumstances.

The most damning criticism of Kant is directed at a consequence he derives from the categorical imperative, namely that telling lies or breaking promises is always wrong, because neither of these acts can be consistently universalised: a liar couldn’t coherently desire a world where everyone lies, for instance. The success of the liar is grounded in the fact that other people, as a general rule, tell the truth: the liar could therefore never wish that lying became a universal practice; he just wants to be the exception to a rule he wishes others to obey.

This is all very well, say Kant’s critics, but there are plenty of situations in which reasonable people would regard not lying as morally reprehensible. In the famous example, suppose an SS officer knocks on my door looking for Jewish refugees to drag off to certain death, and I am hiding some. If I tell the officer that I am indeed hiding Jews, then I have faithfully upheld my Kantian duty to tell the truth, while grossly neglecting my greater duty to protect innocent victims from harm. So it seems ridiculous to suggest that I must place my duty to tell the truth above all other considerations. It is a major weakness in Kant’s theory that he offers no remedy to such situations.

In The Right and The Good (1930), W.D. Ross famously amended Kant’s ethics with his notion of prima facie (i.e. apparent) duties. Ross said that while we do have prima facie duties not to lie, not to steal, not to kill, etc. there are always exceptions to those prima facie rules. But this seems to me a rather vague, unsystematic remedy.

However, perhaps there is another way to rescue Kant’s ethics and restore his reputation. Consider that there are plenty of situations in which a person’s behaviour can be interpreted in more than one way. Most of us would wish to live in a world in which others are charitable towards us by granting us the more reasonable interpretation of our behaviour. Usually this will mean that my action is defined not merely with reference to its external form, but according to its ultimate aim. (Kant himself insisted that the only thing that could be good without qualification was ‘the good will’.) This is to say, the intention of my act, the end towards which it aims, is the primary consideration, while the means to that end is secondary; and the charitable judgement is the one that looks at the overall end or intention. My intention in lying to the SS officer is not primarily to lie, but to save innocent people from harm: lying is merely the means to that end. The more charitable interpretation of my action therefore is not ‘she lied’, but ‘she protected innocent people’. Interpreted charitably, then, the agent’s maxim in my example is: ‘always protect the innocent by reasonable means’ rather than ‘always lie’. Furthermore, I could wish that the overall maxim be followed by anyone in the same circumstances.

This outlook is arguably consistent with the ethics of St Thomas Aquinas, who understood that the discernment of ultimate values is essential to the moral evaluation of actions. Thus, doing some form of apparent evil (like telling a lie) is not forbidden if a moral agent can reasonably judge that it is a necessary means to the achievement of a greater human good. Aquinas illustrated this with an example from Book I of Plato’s Republic. The idea that one should return borrowed property to its owner is generally a reliable guide to right behaviour; however, when we know that the owner is demanding we return a weapon so that he can use it to commit murder, we can ignore that general norm because it conflicts with the greater good of protecting human life. Our action would be morally interpreted as a single act – protecting innocent life from harm; not as stealing property (a vicious act) and protecting human life (a virtuous act).

The ‘principle of charity’ demands that we should opt for the more reasonable interpretation of other peoples’ actions, which usually means judging their overall intentions. In describing the maxim that the agent is acting upon, we must extend to him the same charity that we would hope to get in return. Yet if we can universalize this principle of charity towards the description of other people’s actions, then it seems there is a Kantian method for treating situations in which duties conflict: in a Kantian categorical way, we could still require that the maxim of action – defined vis-à-vis the overall end towards which it aims – be one that an agent could wish to universalise.

© Dr Terri Murray 2014

Terri Murray has taught philosophy and film studies at Hampstead College of Fine Arts and Humanities since 2002.