Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Would Kant Have Worn a Face Mask?

Todd Mei says yes, as a duty of practical reason.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) is famous for his moral philosophy of the Categorical Imperative. With rigorous logic he argues that we should treat other people as ends in themselves, not merely as means to our own ends. He builds on this to say that we have certain duties towards ourselves and others that must be performed regardless of extenuating circumstances. Prominent among these duties are not lying and not committing suicide. These can be seen as duties to preserve the moral, reasoning person, and the natural, human creature respectively.

It seems clear that if Kant were alive today he would endorse wearing a face mask during pandemic conditions. First, doing so would help preserve one’s own natural being. Second, it would help to protect the natural being of others, as well as respecting others as moral, reasoning persons who recognise the same obligation towards you. Finally, recognising the first two obligations and fulfilling them would be a form of respecting yourself as a moral, reasoning being. But apart from these implications, is there any more that we can gain from Kant concerning this issue?

Yes. Some people, such as American anti-government activist Ammon Bundy, claim that rules requiring masks are a form of tyranny. Kant’s distinctive understanding of morality and freedom can help show why this is confused at best.

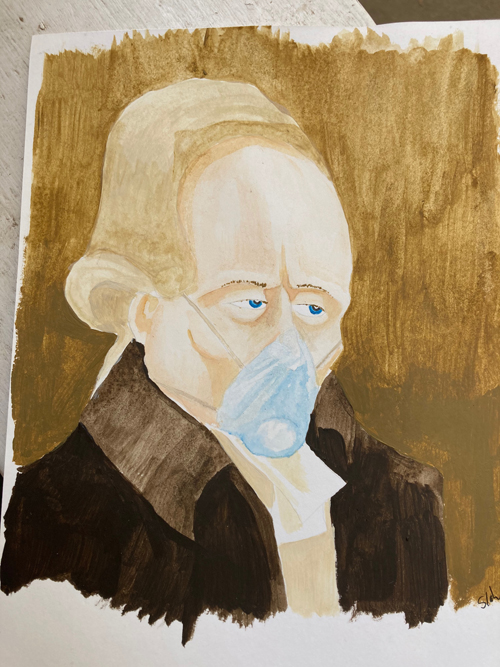

Immanuel Kant doing his duty, by Stephen Lahey 2021

Morality vs Legality

Kant understands morality in terms of duties that we owe to ourselves and others. Recognising when a duty is required of us involves the use of reason to grasp a moral law that might guide our actions. For instance, we follow the duty not to lie not because of fear of punishment; rather, we use reason to discover that if we did not have a general constraint against lying, we could never know when the truth was being spoken. Allowing for an exception to this duty can create a slippery slope where the truth-asserting role of speech becomes impossible.

The use of reason, for Kant, is a way of individually determining what we ought to do based on necessary and universally true moral laws. In fact, in rationally apprehending the moral law, legal and conventional rules become redundant. If we rationally understood why it is important to help those in dire medical need, we would not require Good Samaritan laws. Conversely, we often find that even when there are legal regulations, those abiding by them may not understand the reason for their existence, and so may follow them only out of fear of sanctions.

So how might this conception of morality and reason help us better work through the public controversy over mask-wearing?

You Say ‘Freedom’, I Say ‘Freedom’

Opponents of mask-wearing laws tend to cite the right of individuals not to be subject to unnecessary or coercive restraint. Political philosophers call this right ‘negative liberty’. Such mask opponents allege that requiring mask-wearing constrains an individual’s freedom.

One problem with the negative liberty concept is that it doesn’t help us determine for what ends our freedom exists. This lack tends to reduce freedom to trivial motives relating to preferences or desires. Here one has to do a lot of work to include ends that benefit both oneself and others. To compensate for this lack, one can add a proviso: freedom of action should be allowed only in so far as it does not disadvantage or harm others. Do those who insist on their right to not wear a mask take this proviso seriously? Probably not.

By way of contrast, we saw that Kant understands what it means to be human in terms of our capacity to reason and so recognise certain obligations we have towards ourselves and others.

This is significant for how Kant conceives freedom. He does not take the absence of restraint on action to be the essence of freedom, largely because such freedom can contradict our capacity to reason. For instance, due to questionable influences, we might freely act in ways that cause us harm – a rash act motivated by lust, for example. Instead, Kant conceives freedom as acting in accordance with what is either rationally necessary (in terms of duties) or permissible (in the absence of a duty). While this view may seem constraining at one level – because it implies the realisation that we have to act in one way and not another – it presumes freedom is predicated not on the individual acting alone, but on the individual in relation to others who share the ability to reason. So where does this put the view that decries mask-wearing?

If I am accurate in my characterization of Kant’s moral philosophy, those who say mandating mask-wearing is ‘tyranny’ are confused about what it means to be a capable human. It means being able to reason about how we should act towards others. The end of Kant’s notion of freedom is respect for all rational beings. In contrast, the negative view of freedom, in lacking in this implication, is silent here at best. In practice, its end is self-absorption. This is apparent even if we do grant that one has a right not to wear a mask, for one person’s freedom in this respect would effectively curtail the freedom of others who are medically vulnerable, for instance. If we follow Kant, we realize there is an obligation to respect others just as we respect ourselves.

© Todd Mei 2021

Todd Mei is former Head of Philosophy at the University of Kent and now works as a philosophical consultant for businesses at Philosophy2u.