Your complimentary articles

You’ve read two of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Kant & Rand on Rationality & Reality

Dana Andreicut tells us about their philosophical differences and similiarities.

Ayn Rand’s 1957 novel Atlas Shrugged has recently made a comeback after more than half a century, largely due to the financial crisis and the reassessment of capitalism brought about by it. The novel presents a provocative thought experiment: industrious free-market proponents oppose an all-encroaching authoritarian government by going on strike. Production and innovation grind to a halt, leaving a crumbling American society behind.

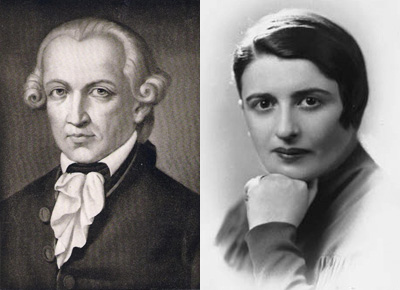

Whilst timely in its exposure of an old battle between left and right, the novel goes much deeper than that. The book in fact brings to the fore an interesting philosophical dispute between Rand and one of modern philosophy’s finest, Immanuel Kant. The two have often been portrayed as philosophical opponents. What scholars have failed to reveal, however, is how much the two share when it comes to the nature of rationality and the self.

Kant’s Transcendental Idealism

Kant put forward his transcendental idealism in the eighteenth century. According to this doctrine, individuals perceive external events by means of sensory experience as taking place in space and time; however, space and time are merely the mechanisms (‘categories’, Kant calls them) through which humans perceive and understand the world. To use a metaphor, it is as if we are wearing blue-tinted glasses. Through these glasses, we perceive the world to be blue. However, the world may in fact be of a different colour, or devoid of pigment altogether, and if we were able to take off our glasses, we would see its true colour. But we cannot. So it is with space and time. We cannot help but perceive the world in space and time. Our understanding is defined by our wearing blue-tinted glasses, or, to transcend the metaphor, by our perception of events as taking place in space and time. However, the world as it is in itself, as Kant terms it (“die Welt an sich selbst”) does not have these humanized features of space and time. Furthermore, because we cannot get outside of the terms of our own experience to perceive the world, we cannot know what its true features are. Kant concludes that we only have access to the phenomenal world of our experience, leaving what he calls the ‘noumenal’ world, the world as it is in itself, forever out of our reach. This is the heart of Kant’s transcendental idealism.

However, not knowing the the world as it is in itself is not a disaster. We can know many things about the world and ourselves merely by staying within the realms of our reason. Sticking to these boundaries in the Critique of Pure Reason (1781), Kant proves that causation and substance must exist. Furthermore, he goes on to make a significant philosophical leap by defining what it means to be conscious of one’s experiences and how the self brings these experiences together.

Writing before Kant, Scottish empiricist David Hume argued that the idea of the self as a persisting subject of mental states must arise from some persisting impression (experience) of the self. He went on to argue that such an impression does not exist, and hence that the ‘self’ is our label for what is merely a collection of perceptions: “For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred…I never catch myself at any time without a perception,” Hume argued (A Treatise of Human Nature, 1739).

Kant disagreed. He said that one could not grasp anything about the world if one was merely a disorderly bundle of ideas and perceptions. There is instead something we can call the self, which brings these perceptions together in an unified experience, he argued. And furthermore, what makes our experiences meaningful is the fact that we are the agents of these experiences.

To explain how this self works, Kant put forward his view concerning the unity of consciousness by distinguishing the steps that we go thorough when experiencing external events. Firstly, we are given information by means of the senses; then our minds combine the parts of this information into a complex unitary representation. Take for instance the image of a house. Our senses convey information about a door, of a couple of windows, of a roof (as seen through the categories of space and time, of course); but it is only by means of our rational capacity that we combine all of these elements of experience into the concept of a house. Kant calls this process of combining various parts into a whole ‘synthesis’. However, for Kant, for a mind to achieve synthesis presupposes rational activity conducted by a single subject ‘overseeing’ the combining. For this synthesis of our sensory information into meaningful experiences to be possible, then, we need to possess a distinctive self-awareness. Kant argued that when putting the various pieces of our experience together, we are aware of ourselves as the agent of a temporally extended activity of experience synthesis. Offering a rather complex philosophical argument, then, Kant urges people to dismiss Hume’s skepticism and embrace the idea of a unity of consciousness, a self, which makes experience possible in the first place.

Kant had many achievements in the Critique of Pure Reason, but he also showed that there were many limits to what one could prove. In a section entitled ‘The Transcendental Dialectic’ he spells out what kind of information we will never be able to grasp. In this section he introduces the transcendental ideas – concepts of pure reason “to which no corresponding object can be given in sense-experience.” These ideas include notions of the self as an immortal entity, the universe, its limits in space and time, as well as its origin, and finally, the idea of God. There are also antinomies, which are dichotomies apparently unresolvable by reason, such as whether the universe is finite or infinite. Despite this apparent ignorance inherent in our reasoning faculty, Kant remained optimistic. Knowing that the world of our experience is governed by a causal order, and that we possess rationality and self-awareness, provides us with valuable guidelines by which we can live our lives.

Rand’s Objectivism

Writing nearly two hundred years later, Rand dismissed Kant’s idealism from the start. She launched the objectivist movement, arguing, contrary to Kant, that there is no distinction between appearances and the world as it is in itself – the two are one and the same. This in turn makes it possible for human beings to gain perfect knowledge of their surroundings: objective reality is in front of us at all times, and perception is our key to taking in this reality. Not unlike Kant, reason is at the heart of what Rand called the self. Rationality is our defining feature, as it enables us to take the material given to us by the senses and process it in a rational manner, that is, to understand it. And if all there is to the world is what we can readily perceive and understand, then there are also no unanswered metaphysical questions. A convinced atheist, Rand did not explain in her work how the world came about, or whether there was an uncaused cause. For a Randian, these seem to be uninteresting questions, simply because the answer to them is obvious. Temporary as our existence is, we can make the most of our time on Earth via our rational capacity until one day we cease to exist. Beyond this, there is nothing.

Rand’s view of human flourishing, inspired by Aristotle, had no limits. Human beings should pursue their individual self-interests in an attempt to achieve their true potentials. For Rand, capitalism emerged as the ideal setting for human freedom, posing no constraints on thinking and entrepreneurship, and allowing human flourishing at its fittest. By capitalizing on their talents and doing what is best for themselves as rational beings, people are in fact choosing the moral course of action. By contrast, tampering with capitalism or with individual freedom more generally would bring about devastating consequences. This is neatly illustrated by the crumbling image of American society in Atlas Shrugged, once America’s best laissez-faire brains decide to go into exile.

In a TV interview given after the publication of Atlas Shrugged, Rand referred to Kant as “the most evil philosopher of all times.” No doubt she had various things in mind here. For one, Kant was a believer in a morality based on duty, which, among other things, denied people the right to act solely out of self-interest. But Rand condemned his transcendental idealism even more strongly than his moral views. Rand dismissed Kant for his stubbornness in labeling human knowledge as limited because of the transcendental ideas, and denying us knowledge of the world as it is in itself. What has escaped many commentators, however, is the fact that the two were more in agreement when it came to the nature of rationality and the self. To understand this common basis we need to go back a hundred and fifty years before Kant, to seventeenth century France.

Refuting Descartes

Undergraduate philosophy students often begin their studies of the subject through René Descartes and his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641). In it, Descartes starts by arguing that sensory experience is unreliable and can lead us astray. Descartes then embarks on a quest for an ultimate point of certainty, on which he will build his philosophy. What comes out of this search is his key phrase “cogito ergo sum”, “I think therefore I am”. Even if everything around us remains uncertain, even if we are convinced that we are in fact hallucinating, we can at least say that there is a hallucinating entity; and that entity is the thinking thing, or our rational self. According to Descartes, because it can be believed in independent of a belief in his body, the self is therefore an immaterial substance whose essence is thought.

In a brief yet famous section of the Critique, Kant takes on the French philosopher and puts forward ‘The refutation of idealism’. What he has in mind here is not his own transcendental idealism, of course, but what he regards as Descartes’ ‘problematic idealism’. “The mere, but empirically determined consciousness of my own existence proves the existence of objects in space outside myself,” Kant argues, concluding, contra Descartes, that the self cannot exist independently of the world it perceives.

The argument for this unfolds as follows. Each of us has a history of subjective experiences that stretch back in time over hours, days, years. What enables us to order these experiences is the fact that we correlate them with the states of an enduring reality that exists independently of our experience. So we need the enduring reality of the outside world in order to be aware of the ordering of our subjective experiences, and so of ourselves as beings enduring through time. Kant thus believes that he has proved that Descartes was in fact confusing the idea of a unity of consciousness with the idea of an immaterial self which can exist independently of the world we experience, when in fact the self which provides the unity of consciousness is conditioned by the world.

Rand agrees. “A consciousness conscious of nothing but itself is a contradiction in terms” she argues in Atlas Shrugged, using the voice of John Galt, the novel’s central character, to deliver the message. As part of the famous John Galt speech, she expands her not so unKantian view of consciousness and rationality:

“Existence exists – and the act of grasping that statement implies two corollary axioms: that something exists which one perceives and that one exists possessing consciousness, consciousness being the faculty of perceiving that which exists.

If nothing exists, there can be no consciousness: a consciousness with nothing to be conscious of is a contradiction in terms. Before it could identify itself as consciousness, it had to be conscious of something. If that which you claim to perceive does not exist, what you possess is not consciousness.”

Kant’s argument sends the same message. Consciousness and the object of its awareness go hand in hand. Descartes’ thinking thing cannot exist in and of itself in a void. It requires the world as its object of perception.

This is where the agreement between Rand and Kant comes to end. In that very speech, John Galt goes on to state that the rule of knowledge is that “A is A”, that “a thing is itself”, that “existence is identity” and “consciousness identification”. Rand, through Galt, is here reiterating her disagreement with Kant’s distinction between the world as we perceive it and the world as it is in itself. She goes on to argue that as human beings we gain information by means of the senses, and we grasp this information and use it via our rational faculty.

Immanuel Kant & Ayn Rand – Closer than you might think

Rand Standing At Kant’s Crossroads

While Rand may have been reluctant to accept it, Kant’s refutation of Descartes’ problematic idealism and her own definition of consciousness in Galt’s speech show that common ground between the two philosophers does exist. However, there remains a fundamental disagreement between them concerning the actual nature of the world and the limits of knowledge. For Rand the answer to these puzzles is simple. The world is as we perceive it, nothing less, nothing more. Limits to our knowledge? There are none. Kant, on the other hand, would argue that while our unity of consciousness operating together with our senses offers enough information to allow us to go about our daily lives, we are severely limited in our ultimate knowledge of reality.

Both this disagreement between the two, as well as their partial agreement on the nature of the self, bring to the fore the fundamental questions of epistemology and metaphysics: What is the self? Is there an immortal soul? Is there an uncaused cause? And does it matter if we can’t answer these questions?

No, it doesn’t really matter, Rand would say: there is little to be said about the origin of the universe, and there’s definitely no life beyond the one we have now. All we need to do is pursue our rational self-interest and fulfill our potential. Whether people can be satisfied with this response remains debatable. Embracing Kant, there remains the hope that ignorance might one day make room for truth. A final verdict on the correctness of either philosopher is yet to be reached.

© Dana Andreicut 2014

Dana Andreicut is an economic advisor at the European Parliament, and is always happy to tackle a new philosophical riddle. She holds an MSc in Economics and Philosophy from the LSE in London.