Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Obituary

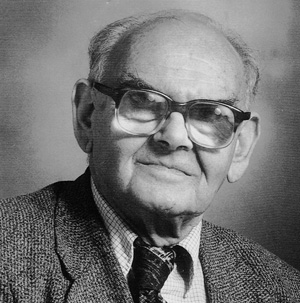

Peter Rickman (1918-2014)

Anja Steinbauer and Rick Lewis remember a friend and a scholar.

Our long-time contributor and good friend Professor Peter Rickman died on 10th April aged 95.

Born to a German-speaking Jewish family in Prague, Peter Rickman began his first degree there in the late 1930s. He fortunately was away studying in Britain in 1938, first at the University of London, then taking his DPhil at Oxford University where he was the same class as Iris Murdoch. He lived in Britain for the rest of his life.

The two great intellectual loves of his life were literature, an interest he developed at the age of six, and philosophy, which he discovered ten years later at sixteen. He remained true to these for the rest of his life, turning them into passions as well as fields of breathtaking expertise. For recreation Rickman enjoyed playing chess. I never saw him lose a game, and by all accounts in his younger years he used to be a Yorkshire champion.

Peter Rickman was a true philosopher, a remarkable, warm and humorous individual and an outstanding teacher. Living and breathing philosophy he even complained that the information on the packaging of the toilet paper he had bought on his domestic shopping trip was tautological: “Will fit any suitable container.”

Rickman was so keen on Kant that the only way for anyone to fall out with this genial and tolerant man was to attack or misconstrue (as he saw it) Immanuel Kant’s ideas. He thought it a great joke that his own birthday fell on Kant’s parent’s wedding anniversary. However, another major area of philosophical engagement was with Wilhelm Dilthey and hermeneutics, the philosophical study of understanding and interpretation. Rickman was a pioneer in the field and the foremost scholar of Dilthey in Britain.

After initially lecturing for some years at Hull University, he moved to City University in London where he co-founded the Humanities Department and for many years headed the Philosophy unit within it. He contributed many articles to Philosophy Now over two decades, starting with “The Philosopher as Spy” way back in Issue 3 (1992) and continuing right up to Issue 101. He also was a sort of patron saint (as his friend Raymond Tallis put it) to the Philosophy For All (PFA) organization in London; the founders of PFA first came together in his philosophy classes in the 1990s.

In 2009 Peter Rickman gave his last public lecture in London, to Philosophy For All. The meeting was in the upstairs room of a pub, the Exmouth Arms. Rickman’s legs were giving up on him by then, and friends had to half-carry him up the narrow stairs to the venue. Then he realized that he hadn’t visited the gents, so he was carried downstairs again to the bathroom, and then back to the upstairs bar once again. By this time he looked so exhausted that we wondered if he would be able to give his talk at all. He did. As soon as he began to speak, he seemed to forget his physical infirmities completely. He held the packed audience of around 100 people spellbound for 45 minutes while he gave a fascinating lecture of the highest intellectual standard on hermeneutics and the different kinds of knowledge appropriate to different branches of academic enquiry. It was peppered with jokes, as usual.

Peter Rickman had a huge fund of jokes, and used to scatter his lectures liberally with them. One favourite of his was an illustration of hermeneutical problems: A young couple are travelling in a car, with the man driving. He slips an arm around her shoulders. Concerned, she says “Shouldn’t you be using both hands?” And he replies “I would like to, but the old bus won’t steer herself.”

His wit never failed him: Once Rickman applied to City University for a sabbatical so that he could finish writing a scholarly volume about the works of Wilhelm Dilthey. He had a meeting with the administrators, who were reluctant to release him from his teaching duties. One of them suggested to him that, since the university would have to pay for replacement teaching staff while he was away, he should agree to pay it any royalties he earned from the book. Rickman thought about this for a minute and then replied that he didn’t think that would be quite right, but added “but you can have the film rights!”

Rickman’s interest in ethics wasn’t just theoretical. After losing his first wife to cancer, Rickman over many years quietly gave substantial sums to cancer charities. Rickman kept fit into his late eighties with a daily outdoor swim in all weathers. He swam with a friend called Gromyko, a nephew of the former Soviet foreign minister of that name. In winter, they used to break the ice so that they could swim.

Despite the problems with his legs, Peter was physically active until very late in his long life, and worked on philosophy until the end. In fact he has a new book called The Philosophy of Literature coming out soon. Last year he went on a honeymoon cruise to St Petersburg with his new wife Jodie.

All his life Rickman was fascinated by the exploration of the nature of philosophy, and in a series of early articles in Philosophy Now he tried to throw light on this by comparing the philosopher to (for instance) a spy, an actor, a lover and a joker. Rickman published numerous books which were translated into many languages, including Japanese. Here are some of his works: Philosophy in Literature, The Challenge of Philosophy, Preface to Philosophy, The Adventure of Reason, Dilthey Today: A Critical Appraisal of the Contemporary Relevance of His Work, Wilhelm Dilthey: Pioneer of the Human Studies and he also edited Dilthey: Selected Writings. He even published two very readable thrillers, Paperchase and Haunted by History.

We will miss this kind, versatile and witty thinker; there will now always be a distinctly Rickman-shaped gap on the London intellectual scene.