Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Philosophical Library

Rick Lewis on libraries, philosophical classics, unexpected discoveries and the challenges of a digital age.

I remember our school library mostly as a place to keep warm and shelter from the rain and playground bullies. It did, however, contain an eclectic selection of books of varying vintages, and idly browsing them gave me my first taste of what it is like to make unexpected discoveries in literature. Once I found a translation of The Clouds, by Aristophanes. That was the satirical play that Socrates blamed, at his trial in 399 BC, for having influenced public opinion against him. But back then I had barely heard of Socrates so I found Aristophanes’ witty send-up of the philosopher and his students a little difficult to follow. A couple of shelves further up, one wet Tuesday, I found an astronomy textbook from the late 19th century, that included a section explaining why space travel would always be impossible (because in space there is no air to push against). And one day I discovered a book by Albert Einstein. It wasn’t his excellent popular guide to his own Theory of Relativity. Called Out of My Later Years, it was a collection of essays on all sorts of topics in morality, religion, culture and international politics. It may be the nearest that Einstein came to writing an actual philosophy book, unless you count General Relativity itself as being philosophy. (And why not? Isn’t it a dazzling triumph of metaphysics, developed from basic underlying axioms with ruthless clarity, despite the counterintuitive conclusions, until it finally gives us a completely new understanding of the universe?)

A library is a place where you expect the unexpected and a single passing reference can send you off to another book on another shelf, and each book might contain dross or might contain a whole universe of thought. But I had forgotten that book of Einstein’s essays until recently I accidentally made contact with its publishers, and discovered that the reason they publish this and six other books by Albert Einstein is rather interesting. So of course I felt I should share it.

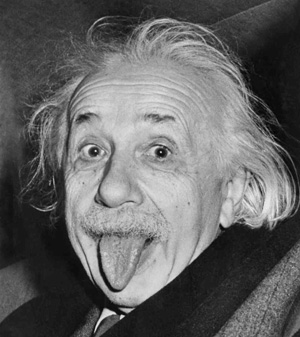

Einstein leaving a dinner party in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1951

It seems that after he emigrated to the United States in 1933 Einstein kept a particular affinity for German language and culture. In New York he made contact with other German-speaking refugees and immigrants, among them a Romanian-born philosopher called Dr Dagobert D. Runes. Like Einstein, Runes was a humanist, a civil rights activist and an admirer of Baruch Spinoza. The two become close friends. Runes knew almost everyone in émigré circles, and hit on the idea of publishing books by the brilliant European exiles he knew. In 1941 he launched The Philosophical Library to do just that. Apart from Out of My Later Years (1950), the seven books by Einstein that he published included several collections of letters, one of which is a book of Einstein’s correspondence with his translator discussing how best to translate various passages of Einstein’s work. The value of this to anyone trying to clarify Einstein’s meaning on different points is obvious. Then when Runes himself edited a Spinoza Dictionary, Einstein wrote the foreword.

The Philosophical Library continues today, still based in New York City but now under the direction of Dagobert Runes’ daughter Regeen, who remembers playing ‘hide-and-go-seek’ with Einstein when she was a small child. Over the seventy years of its existence the company has published more than 2,000 titles, mainly on philosophy, psychology, history and religion. Like the library at my old school, its catalogue is charmingly eclectic, but includes works by 22 Nobel Prize winners. Apart from Einstein’s books its best-known publications include Tears and Laughter by Kahlil Gibran, Classical Mathematics by Max Planck, the English edition of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, and works by Karl Barth, Martin Buber, Bergson, Dewey, Simone de Beauvoir, Jaspers, Royce and many others.

As technological change accelerates and independent publishing companies either fold or merge into giant corporations that bestride the oceans, the survival of small-scale philosophy publishing depends on discovering models which work both financially and in terms of meeting the needs of readers. The Philosophical Library uses two such models. Firstly, it publishes classics from its vast back-catalogue as e-books, as this avoids much of the financial risk involved in printing and distribution. Secondly, it offers a ‘print-on-demand’ service, whereby it arranges the printing of a single copy of a book once it has received an order.

The Philosophical Library manages an astonishing legacy of 20th century classics. By contrast, Project Gutenberg takes a completely different approach for older books which have passed out of copyright in the United States, which happens 70 years after the death of the author. The books are scanned and proof-read by an army of volunteers and around 45,000 are now available for free download, though only about 100 of those are philosophy books. The project’s founder, Michael S. Hart, passed away in 2011 but his legacy marches on. Finally I should mention another great project for public domain works: LibriVox. This is a website containing free audiobooks, recorded by volunteers. Its collection includes around 300 philosophy titles and it is a great resource both for visually impaired people and anyone else who likes to listen to books.