Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

How Darwin Ruined My Sex Life

Anika Benkov uncovers a question that’s been left unanswered.

This isn’t a story about sex. It’s not even really a story about Darwin. This is a story about one generation’s loss of philosophy, and the strange world we’re living in after the fact.

A common term I’ve heard used to describe the millennial phenomenon of casual, meaningless, and often alcohol-induced sex, is ‘hook-up culture’. But I wouldn’t really call it a culture. That implies a set of rules that we’ve agreed to follow. In my experience, the prevalence of casual sex is more the result of entropy. It just sorta happened.

Here’s another way of putting it. Before the Sixties there were two kinds of sex: the marital and the non-marital. Sex wasn’t really talked about; but when it was, the socially acceptable kind was the married kind. Anything else was fine, but only if you didn’t get caught. After the sexual revolution, we’d like to think that sex has gotten better: that people are more enlightened about what makes sex good, for men and women. People aren’t punished by a strict system of absolute chastity followed by absolute fidelity. In fact, we’ve done away with those near-unattainable standards of chastity and fidelity almost entirely. What we didn’t anticipate was the unravelling that would follow, particularly in the late Nineties, of what some would call ‘the dating scene’ but which I would argue to be our concept of ‘a relationship’ in general. One of the things I’ve heard all too frequently when I start to get into what I think might be a ‘relationship’ is, “I don’t want to put a label on it.” Moreover, the terms ‘boyfriend’ and ‘girlfriend’ carry all the weight of someone’s luggage hitting your bottom step. They imply something… long-term. Serious. To say the least, we’ve come a long way from ‘getting pinned’ and ‘going steady’. I imagine that nowadays, if I approached a potential partner suggesting we ‘go steady’, the next thing they’d ask me is, what sex position is that, and where did I learn it?

Donna Freitas attributes this shift to a world where hooking up is normal largely to our generation’s increasingly impersonal social interactions via text, Facebook and Twitter (The End of Sex, 2013, p.8). However, to me the shift seems to be part of the wider problem of the changing language we use to talk about relationships; or rather, the problem of the language we don’t use to talk about relationships.

We now tend to dismiss the old elaborate legal, emotional, religious, and socially constructed labels for relationships – wedded, wedlock, chaste, cheating, whorish, steady, girlfriend, boyfriend – as archaic, outdated. But that’s not because our generation has come up with a better vocabulary. In fact, I don’t think we’ve come up with a vocabulary at all. So it turns out that abandoning the old standard of marriage hasn’t freed us to explore our relationships; in fact, it’s helped take away our vocabulary to talk about them.

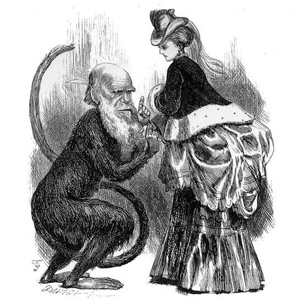

To understand why this is, I want to look at a drastically different type of paradigm shift, which happened in Europe during the mid nineteenth century. Darwin was publishing his On the Origin of Species (1859). Other thinkers, like George Lyell, John Herschell, and John Stuart Mill, were starting to come up with new methodologies – the word ‘scientist’ was coined in this era by Darwin’s contemporary William Whewell (see D.L. Hull in the Cambridge Companion to Darwin, 2003, p.177). In particular, Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection offered an entirely new way of looking at the world by positing a naturalistic mechanism for the development of species.

We all know about the old Creationism-versus-Darwinism debate. Many still find a point of controversy between the arbitrary force of natural selection and the Judeo-Christian idea that God created the world and all the species in it. Yet more than this theological problem, I’m interested in a philosophical problem Darwin’s theory posed. According to On the Origin of Species, the survival and adaptation of a species comes partly out of randomness. This is what allows the continual existence of what Darwin calls ‘polymorphic’ traits (p.35) – traits within a species that continue to vary because their state neither inhibits nor advances the ability to reproduce. The question here isn’t, ‘Why do these traits exist?’, but rather, ‘Why not?’

The question doesn’t move us in the direction of further understanding the abstract nature of a species’ existence. Indeed, Darwin makes no claims to be able to uncover the mystery behind why traits in species vary so much in the first place – that is, precisely how those variations came into physical being. Neither genetics nor mutation were even conceived of in Darwin’s time. So Darwin can’t give us an explanation for the absolute origin and nature of our being; but he can ask, and answer, the more manageable question, ‘Why do the appearances of species change in certain ways over time?’ As Jonathan Hodge and Gregory Radick suggest in their paper ‘Darwin’s Theories in the Intellectual Long Run’ (Cambridge Companion to Darwin, 2nd ed., p.258), this is a fundamental intellectual shift away from metaphysical philosophizing – that is, away from thinking in terms of the connection between something’s abstract meaning and its physical expression – to thinking solely about something’s physical expression. And since the 1850s, science has made remarkable progress on such purely material grounds, advancing not only our health and prosperity as societies, but also advancing itself through the production of instruments that allow us to see ever more, whether it be orbiting planets or microscopic species living in Arctic pockets.

Ironically, the technology that’s given us such insight into some aspects of our world has had a significant role in taking away insight in others. Along with high powered microscopes come smartphones, iPads, Twitter and Facebook. This is a world in which human faces are seldom seen, and language is stripped to a bare minimum; a world of wink faces and LOLs.

In many ways, our generation’s shift from thinking about sex as part of an abstractly defined relationship, to hooking up, is like the Western world’s shift away from abstract philosophy towards science as a primary mode of thinking. We’ve plunged into the physical mysteries of sex without a second thought to their abstract implications, including emotional. In short, the question, ‘Why have sex?’ hasn’t gone away; we’ve just stopped trying to answer it.

Indeed, perhaps on a grand philosophical scale the question is unanswerable. Sex is so complex and distinct for individuals that the variety of possible personal significances are likely limitless. Like Darwin’s theory, sex involves so many unknown, yet-to-be-discovered variations. Not just variations in people, in their personal preferences; but variations in a specific smell, in a certain moment, in the way the light is hitting someone’s skin, or in a song that’s playing at the time, or in a conversation you just had. A particular way of touching, holding. Why does it feel this particular way? Is it biological? Chemical? Is it emotional? We’ve inherited a language of sex that we can’t speak. We know about this language, and yet it feels like it’s been lost to us for millenia. Translation seems impossible: the prospect of parsing the numerous, endlessly-varying meanings of physical touch and emotional entanglement into neat, philosophically-rigorous definitions would be not only laborious but foolish to attempt. How can you attach a fixed meaning to something that’s so vast and constantly in flux?

No wonder then that we don’t talk about relationships. The impossibility of coming up with a new name to define intimacy, or rather to define the intimacy that we want, is too daunting. At least if you’re going steady, you have someone else to try and figure things out with. But in the new millenium we move alone in throngs on the dance floor. We don’t have definite words – right or wrong – that tell us what sex is, or what a relationship is. Sometimes we don’t even have a full person to communicate with – just a handful of cryptic texts, an accumulation of disparate and fleeting impressions, random grinding and groping and kissing and caressing, that ultimately leaves us grasping for meaning in the dark. We turn the lights off so we don’t have to look; we turn the music up so we don’t have to talk, so we can dance a little longer, distracted from the question that continues to go unanswered.

© Anika Benkov 2014

Anika Benkov is a creative writing major at Columbia University. She is currently in a relationship and has stopped pursuing answers to questions.