Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

The Way of Love by Luce Irigaray

Michael Williams surveys the prospect of The Way of Love.

In 2004, Channel 4 TV in Britain began a fascinating series called The Sex Inspectors. In each programme, two experts follow the dysfunctional sex lives of a particular couple and then offer advice. The advice is on two levels. First there are new sexual techniques to learn, and then there are new communication skills to practice.

Whilst I imagine French-Belgian philosopher Luce Irigaray would not wish to belittle such a skills-based approach, she wants us to see that our whole way of relating to one another has many deeper layers and dilemmas than such an approach would suggest. New techniques could never achieve the communion and poetry that she sees as essential to human relating. What is required is a new way of thinking about how we communicate, even about how we perceive our relationships.

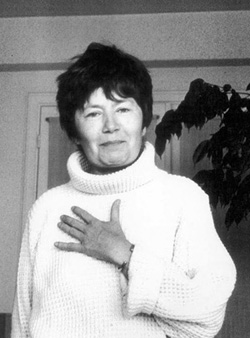

Luce Irigaray: “I love to you”

Irigaray’s fundamental concern in this book is the difference between subject-object relationships and subject-subject relationships. Our current languages and cultures, especially those of the West, are subject-object oriented. In Irigaray’s estimation, our present languages are riddled with masculine forms which prefer the naming and taming of the other. It turns the other into one of my projects. Even the language of love – “I love you” – tends to treat the ‘you’ as the object of my desire. Irigaray calls for a new language that is more active in valuing the other subject. She suggests “I love to you” might be better for this purpose. Here ‘love’ is an active verb promoting you as a subject as well as me as a subject.

This new language and way of relating it promotes is only possible if we understand the radical difference of the other [person]. He or she cannot be reduced, categorised, named, or organised, without destroying the mystery of otherness that is fundamental to their subjectivity. Thus Irigaray explores the theme of difference which has permeated the thought of Martin Buber, Emmanuel Levinas, and Jacques Derrida, although she does not acknowledge this debt here. Her only conversation partner here seems to be Martin Heidegger.

She calls the new way of being ‘being with’. This way of being can only be explored by understanding that “the human is not one but two.” Gender is a paradigm of this twoness. Twoness means that human beings exist not only for themselves, but also for other human beings. So to be fully human, I have to explore intersubjectivity whilst nurturing the growth of the other and promoting his or her blossoming. I must also respect the transcendence of the other without losing my own sense of respect for myself. We can never ‘be with’ the other if we become servile to them or allow ourselves to be diminished by them. The difference between myself and the other can also never be tied down. It involves mystery and silence, but even our understanding of silence must be open to reformation.

Irigaray claims that this new way of dwelling with other people can reunite philosophy and theology. By adopting subject-subject language, theology loses its tendency to construct a male God in the image of our masculine pronouns. God can instead then become the guarantor of the transcendence between subjects. Philosophy ceases to be the love of wisdom, and becomes the wisdom of love.

If Irigaray is right that people are primarily intersubjective, then this certainly poses a serious challenge to much modern Anglo-American writing on the philosophy of mind and consciousness. No wonder the philosophers in this tradition cannot find the ‘I’. To be human is not to be an I, or an agent, or a consciousness: it is to be a subject in relation to another subject. To be human is not to be an isolated I, or agent, or consciousness: it is to be a subject in relation to another subject.

One weakness of the book is that these views are simply stated as insights. There is little argument, and few reasons are offered. No doubt Irigaray would say that this very desire for reasons (logos) is part of the flawed male agenda. Another weakness is that she doesn’t explore in this book the ambiguous and problematic aspects of difference and alterity (alternativeness) – such as those explored, for example, in Derrida’s Politics of Friendship (1997). For instance, she does not explore the nature of violence, nor whether alterity involves original violence; nor does she explore the connection between friendship and enmity. This leaves me questioning whether Irigaray’s vision of intersubjective communion goes to the depths of the experience of being human.

© Michael Williams 2015

Michael Williams is the former Vicar of Bolton, Lancashire.

• The Way of Love, Luce Irigaray, Continuum, 2002, 198 pages, £16.99, pb