Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

What’s So Simple About Personal Identity?

Joshua Farris asks what you find when you find yourself.

Materialists or physicalists are philosophers who believe that humans are completely physical beings, whereas dualists believe we are minds – sometimes souls – with bodies. Both materialists and dualists are very interested in the nature of personal identity. In the recent literature, there are four prominent basic views on it. The proponents of all these views want to answer the questions, ‘What is a person?’ and ‘How can we identify one?’. Other relevant questions include, ‘Who am I?’, ‘Who am I in certain contexts?’, and ‘Is there a fact of the matter to my being me?’

Let’s look at the discussion over the so-called ‘simple’ view of personal identity. Simple views have commonly been associated with substance dualism (which I’ll explain later); yet lately, there is a new simple view that is a variant of materialism. In this article I wish to contrast these two views in the context of the broader debate on personal identity. The basic views of personal identity I discuss here are: the body view; the brain view; the memory/character continuity view; and the simple view. Additionally, there is a new simple view called the not-so-simple simple view. Defenders of both simple views largely agree in their estimate of the first three views, yet there are some important distinctions between the two simple views, which deserve attention. (There are other views that I do not discuss here, such as the narrative view.)

The Body View

The body view of personal identity: There’s still more to you than meets the eye

Body graphic © Mikhail Häggström, 2012

First let’s consider the body view. It is normally ascribed to Aristotle, but it has some contemporary defenders too. The bodily view of personal identity is the view that persons are identical to their bodies. Generally, defenders of the body view do not identify persons with one aspect of the body or one physical part of the body, such as the brain. Instead, the person is identical to the body as a whole: I am my body. This is a popular view held by both philosophical and theological materialists. A recent useful treatment of this position is found in David Shoemaker’s Personal Identity and Ethics (2009), Chapter 2. A similar view has been called ‘animalism’. Eric T. Olson defends it in The Human Animal: Personal Identity without Psychology (1997).

Body views encounter some intuitive challenges. Consider the classic novel by Jack Finney, The Body Snatchers (1955). In it, alien seeds come to Earth from outer space and grow into exact duplicates of the bodies of humans. However, no one would assume that the body duplicates are in fact the original humans. Or consider the Harry Potter stories for illustrations of problems with the body view. For instance, in The Chamber of Secrets and The Deathly Hallows, the reader learns of the ‘polyjuice potion’, which can turn one’s body into the body of another simply by dropping the hair of the organism the person desires to transform into into the potion and drinking it. However, no character assumes that this bodily transformation entails the transformation of one person into another. On the contrary, it indicates that there is some fundamental distinction between persons and bodies. (See also my ‘The Soul-Concept: Meaningfully Embrace or Meaningfully Disregard’ in Annales Philosophici, Issue 5, 2012.)

There are additional reasons for rejecting the body view of personal identity. First, we seem to treat our bodies as distinct objects of reflection, meaning that we seem to intuitively believe that our bodies are in some sense distinct from the core of the self in which we identify. When I encounter my feet as objects of reflection, for example, I am intuitively making a distinction between my self and those parts of my body. This intuition is also arguably active when we use parts of our body for different functions, for example, when I pick up a stick with my hand.

Another problem for the body view is the persistence of identity. It is difficult to see how on the body view the same self can persist through time. The body is a complex organism that changes over time; it has the potential to add or lose major parts, and additionally cells are growing and dying continually. However, it intuitively seems that the person is something more fixed, stable, unified, and enduring: that I am the same person through time. So suggesting that the body is identical to the self seems to undermine basic assumptions a person has of their self.

This is not to say that materialists affirming a body view have no answers to these challenges, but simply that these challenges remain significant worries worthy of consideration. For responses to them, I refer you to the literature listed at the end.

According to some versions of the body view, it is not so much that persons are identical to their bodies but that bodies comprise persons. This is known as the bodily-constitution view. I’ll address it later in the context of the not-so-simple simple view.

The Brain View

The brain view: “I’m sorry, I didn’t recognize you without your body on.”

Another popular physicalist/materialist view is called the brain view of personal identity. This is the view that the person is identical to the brain; either to the brain as a whole, or to some part of it, such as the cerebral cortex, which produces the experiences and other higher order mental activity human minds enjoy.

It seems very natural for materialists to identify the self with the brain, given that the brain is responsible for much of the goings on in the body as well as in the mind. Peter Van Inwagen makes a persuasive case for the person being the brain in his Material Beings (1990), Chapter 15.

The brain view is similar to the body view in that defenders of either identify the ‘I’ or person with some physical, biological thing, though the brain view might be said to be more particular. But the brain view seems to have not only the problems of the body view, but other problems all of its own.

Do brains think? Such a question seems very odd. The immediate response seems to be, ‘No, I think’. Usually, when speaking of thinking, we implicitly speak of the person doing the thinking, not of a collection of neurons firing. Something like the following may seem more promising for the brain view: ‘I use my brain to think’ or ‘I depend upon neural functioning for thinking’. However, this is not a reason to think that selves are brains. To say you are your brain because you use your brain to think is similar to someone saying that my hand picks up a stick, so I am my hand. A hand may pick up a stick, but it is a person’s hand picking up the stick: I use my hand to pick up the stick. Equally, it is my brain doing the activity facilitating my thinking; but me using my brain to think with is not equivalent to me being my brain. Thus, the brain view will not work as a satisfactory view of personal identity either.

The Memory Continuity & Character Continuity Views

The memory continuity and character continuity views of personal identity identify a person with their collection of memories or their character states. Some thinkers distinguish between the memory and character views, but they seem closely related. The similarity is that they say a continuous chain of either memory or character states comprises the person. I will take each in turn and critique both. Proponents of either theory might come from the camp of materialism/physicalism, or from the position that persons are immaterial kinds of things.

John Locke is normally recognized as the progenitor of the memory theory in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689). One can understand the memory view and its problems from a thought experiment. Consider Algernon, who lives a long life full of memories of himself in his family, in school, and at work. Algernon is aware of his past life and experiences day after day, and according to Locke his belief that he exists as the same person day after day is linked to his memory of the past events he recalls having enjoyed or endured. But now consider a different person, Bartholomew, who wakes up one day after having had surgery on his brain. When he awakens, he has the memories of Algernon, these having been implanted into his brain overnight. Bartholomew has no recollection of his own previous existence; instead, he just remembers as if he has been Algernon all along. This presents a problem with the memory view because we know that Bartholomew is not Algernon, and Bartholomew has not done the things he now remembers having done.

Clearly, one’s apparent remembering does not necessitate the reality of the events remembered. My belief that I have been skiing in the Alps does not necessarily mean that I have done so. It is conceivable that I have developed false or apparent memories. Perhaps I had a childhood dream of skiing in the Alps, and much later, I came to believe that I had actually done so. It’s the same with Bartholomew: just because he believes he’s Algernon because he has Algernon’s memories, this does not entail that he really is Algernon. In other words, memory is not a sufficient condition for personhood, or a sufficient ground for identifying the person. Nevertheless, memory plays a large role in the formation of personhood, and as such it offers a great deal of evidential support for the idea that this person is such-and-such and not this other person. That is, memory might provide some evidence that a person now is the same person who existed at a past moment, but it is insufficient in itself to account for personal identity.

Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid (1710-1796) developed a similar, and famous, challenge to the memory continuity view against John Locke. Reid uses the example of a boy who grows into a general. In the story, the boy steals from an orchard, which results in the boy’s whipping. As he becomes an adult he changes, taking on new memories and character traits and, in the process, he eventually forgets that he was previously whipped. Would this then nullify the fact that he is the same person as the whipped boy? It seems not. Instead he would be the same person, since he does remember being the same person as a younger self who did remember the whipping. (For more detail, see Reid’s ‘Of Mr. Locke’s Account of Our Personal Identity’ reprinted in Personal Identity, ed. John Perry, 2008.)

The character view of personal identity is closely related to and often lumped with the memory view. On the character continuity theory, a person is identified as the totality of his or her character states. For example, Donny has the character state of being lazy, which is reflected in his work ethic, or lack of it. His character may evolve over time, but his character states won’t all change at one instant and so they provide the continuity to his existence.

The character view does not run into the same problems as the memory view, at least immediately. For example, it avoids a subjective criterion of personal identity such as what you can remember by requiring states of affairs to comprise or designate personhood. That is, character states cannot be as easily altered or manipulated as memories, as they seem much more integral to the person. Having said this, both seem to run into the problem of fully satisfying our common-sense ideas about persons. Intuitively, it seems wrong to identify persons either as a bundle of memories or of character traits and their states. Instead, we think and speak of persons having memories or persons developing character traits. Thus, defenders of a simple view see either variant as an inadequate account of personal identity.

The Simple View

The simple view of personal identity, which on some variants is called the soul view, identifies persons with souls or some other immaterial mental thing. The simple view is distinct from materialist constructions and the memory/character views of human persons. The simple view of persons says that persons are not reducible to matter, nor are a bundle of both material and non-material qualities. The person is not identified with any biological organism – brain or body – and is also distinct from their memories/character states, in that on this view the person must exist for mental items such as their memories and states of character to exist.

The advantage of this view is that I have the power to persist through time, yet I can change qualitatively. The distinct features of the simple view of personhood include substantial independence and/or the endurance of the soul. The soul or mind or whatever else the person is, does not depend for its identity on anything else: it has a kind of identity not dependent on or reducible to other properties or substances. Rather, its existence precedes its properties in some logical sense, thus having a kind of independence from them. This also makes it an enduring kind of thing. If the soul/person were a bundle of properties that fluctuates, then its identity would fluctuate, or so it seems to some. But the soul/person has a stable kind of identity that does not fluctuate according to the various phases it encounters. As a simple substance, it exists in and through the various stages of life as substantially the same thing. On this view, the person is still the same even when going through various changes, and predicating properties of the same person at two different phases is possible. For example, Bruce Wayne may exist through phases as Batman, but he remains essentially the same person in and through these phases.

Substance dualism says that an organism consists of two fundamentally different types of substances. The simple/soul view naturally entails substance dualism because it posits a simple substantial ‘I’ that is contrasted to the complex thing, the body, through which it manifests. A materialist might argue in response that persons could perhaps identify with a simple part of the brain, or some particle in brain or body; but it’s not at all apparent what that part might be.

The Not-So-Simple Simple View

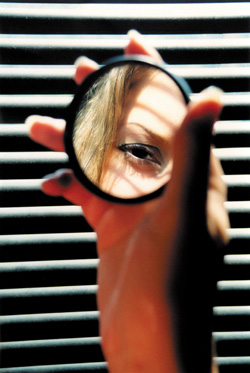

Your handy guide to personal identity

Finally, there is an alternative simple view on personal identity found in the recent literature that deserves distinguishing from the standard simple view. The alternative has been called a not-so-simple simple view of personal identity.

Lynne Rudder Baker, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at the University of Massachusetts, has developed this view, and it has much in common with traditional or standard simple views. She identifies persons with what she calls ‘the first-person perspective’. This is the perspective I have of myself, or the perspective you have of yourself. Thus, persons are here not identical to a body or a brain; neither are persons identifiable with a set of memory or character states; instead, persons are identified with a particular perspective. In a recent work, Baker puts it like this: “A person is a being with a first-person perspective essentially, who persists as long as her first-person perspective is exemplified” (Naturalism and the First-Person Perspective, 2013, p.149), even though defining personal identity in this way is rather circular, and not very informative for the reader, as Baker acknowledges (p.150). As Baker says in her conclusion, “the first-personal view is a Simple View because it provides no informative criteria of personal identity” (p.155).

So Baker points out that her view is a simple view because persons are identified with a perspective but there is no further fact underlying this perspective. However, in contrast to some other views on personal identity, Baker believes that the first-person perspective necessarily depends upon brain mechanisms functioning properly. On her view of the mind, first-person perspectives are higher order properties of the brain. Given this intimate constitutive relationship of brain and person, this view has some similarities to the brain view. However, although the first-person perspective depends upon the brain, the brain alone is not sufficient for identifying persons.

Baker’s view is unlike other simple views of personal identity in that it’s a version of materialism, situated in the natural order of physical causes and effects. Importantly, as shown above, other simple views depend upon immaterial substances. There are also other important distinctions between this not-so-simple simple view and more standard simple views. First, she affirms the notion of gradual existence: the first person perspective comes into being gradually – first in the womb, then as the child matures into self-awareness and reason. This, then, requires Baker to affirm the indeterminate nature of personal existence. This implication may seem rather odd upon reflection, given that on the simple view persons seem to exist or not exist: there is a fact to the matter that’s as absolute as the fact that 1+1=2. Baker argues however that standard views seeing personal existence as determinate and informative means that persons are reducible to something nonpersonal. However, I am not sure that defenders of standard simple views would agree with Baker’s assessment that to affirm that personal existence is determinate and informative would be to reduce the personal to the impersonal. Instead, it may be that each individual human person bears a relation to the self that is neither circular nor uninformative, such that I as a person bear or have a feature that is fixed, determinate, non-circular, yet informative. It is unclear that this feature must be ‘impersonal’, given what Baker has argued and the state of the literature at present.

In the end, then, ‘simple’ views turn out to be not so simple, much as the proposition in the philosophy of religion that ‘God is simple’ turns out to be not so simple.

© Joshua Farris 2015

Joshua Farris is an Assistant Professor of Theology, Houston Baptist University and Trinity School of Theology. He has co-edited The Ashgate Research Companion to Theological Anthropology (2015), and is completing The Soul of Theological Anthropology (Ashgate monograph), and co-editing Idealism and Christian Theology (Bloomsbury Academic).

Further Reading

Good resources in the literature on personal identity include John Perry, A Dialogue on Personal Identity and Immortality (1978); James Baillie, Problems in Personal Identity (1993); John Perry, Ed, Personal Identity (2008); David Shoemaker, Personal Identity and Ethics (2009); Trenton Merricks, Objects and Persons (2001); John Foster, The Immaterial Self: A Defence of a Cartesian Conception of the Mind (1991); Richard Swinburne, The Evolution of the Soul (1997, see especially chapters 8 and 9). See also Swinburne’s essay entitled ‘Personal Identity: The Dualist Theory’. Additionally, see E.J. Lowe’s essay entitled ‘Identity, Composition and the Simplicity of the Self’ in Soul, Body and Survival (2001).