Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

The Art Issue

Art As An Encounter

Daniel Vargas Gómez considers what we encounter when we encounter art.

When Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) wrote Concerning the Spiritual in Art (Über das Geistige in der Kunst, 1911), his purpose was to portray art as the greatest expression of the human spirit. Nor was he the first, and certainly not the last, to propose this link between art and spirituality; before him Karl Friedrich Schlegel (1772-1829), and Romantic thought in general, had developed an approach to aesthetics that highlighted the incompatible nature of human life and modern industrial creations. Nevertheless, the Twentieth Century has witnessed such a variety of art concepts and artistic production that assuming a vision of art like that of Kandinsky’s may seem arbitrary, and even naïve, just because Kandinsky’s vision can argue neither in favor of nor against the value of Twentieth Century radical aesthetic trends, such as conceptual art, among others.

The artistic freedom in at least most of the Western world for the past hundred years has had no precedent in history. Yet at the same time as all sorts of artistic manifestations and movements have appeared, any pretense of finding objective values in art or even implying their existence has become more and more unlikely.

There are two main reasons for this. First is the acknowledgement of the artist’s work as a form of expression which is above all subjective, in the sense that it does not obey received rules on forms or taste. An absolute respect for this subjectivity is required in order for the art appreciator to obtain the most from each individual artistic expression. This respect has made the work of art untouchable in many ways, and more often than not has isolated the viewer from the purposes of the artist. Second, the growth of all forms of artistic movements and ways of expression has resulted in the massive proliferation of the artworks available to the person on the street, making it a Herculean task to keep up even with the mainstream of art. Even as artwork of all kinds has become more accessible to all, there seems to be a loss of perspective with respect to aesthetic thought and purpose since the birth of Impressionism in the second half of the Nineteenth Century. Nonetheless, I believe that Romanticism’s claim that human creativity is a ‘life-force’ has actually been undermined by the substantial growth of artistic work throughout the past century, and in this one too. This growth, as I said, needs to be accompanied by a better understanding of art and artwork, and not only by focusing on the quantitative growth of the industry.

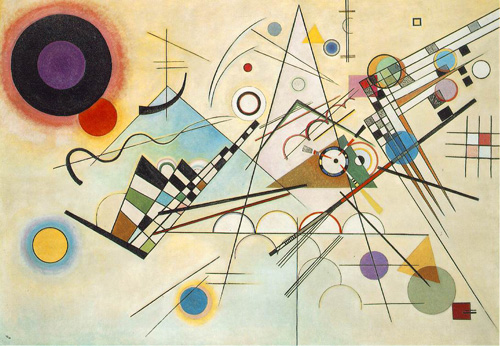

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VIII

The Artist & The Audience

What exactly does the loss of perspective on art mean?

It means that with time art has become more available, yet more difficult to comprehend and admire; and this in turn means that even as there is more art for people to see, that doesn’t necessarily translate into people actually enjoying it.

Does this imply that there may be something wrong with conceptual or abstract art? Absolutely not. The answer to the difficulty is not to make all artworks completely ‘transparent’, saying with this that art must lack its own intrinsic, idiosyncratic intellectual or aesthetic values. The answer, I think, rather lies in understanding a view like Kandinsky’s, especially concerning the relationship between the artist, the work of art, and the spectator.

Let’s go back a step and try to understand what the claimed essence of this relationship is, whether it matters, and if it may (or may not) have implications for the construction of personal artistic values, as well as for the values of society as a whole.

Any work of art poses a great challenge to spectators: the challenge is to fully understand and appreciate that the whole value of what’s presented to them cannot be reduced to a single cause alone, be it pleasure, politics, mathematics, or whatever.

Why would this be a challenge? And if it is such a daunting task, why would anyone care for art? Shouldn’t a painting, for example, be first a pleasure for the eye rather than a challenge for the intellect?

Yet even if many or most of the paintings out there can give enormous amounts of sheer pleasure when beheld, it is not true that grasping a painting only requires one to ‘cultivate the eye’.

The process of apprehending a painting assumes the existence of certain values – such as ideals of beauty; or ‘the sublime’ as in the case of, say, Kasimir Malevich; or in an artist’s portrayal of goodness, and so on – that must be present in the mind and soul of anyone who wants to appreciate the painting to the fullest extent. It doesn’t matter that the intention of the artist may be other than that of simply exciting or ‘feeding’ the eye, for, say, beauty can certainly be found on grounds other than that of color or the harmony of the forms. We can rightfully begin to have at least the suspicion that such values are the subject matter or maybe even the essence we apprehend in the work of art. We may accept then that these values ‘coexist’ with the physical reality of the painting. We can then perceive the painting as something that can be esteemed.

No matter of what type of art it is, it not only presupposes the existence of values for both artist and audience: it also proposes to the observer a particular view upon such values, and sometimes suggests the recognition of new ones. In other words, artworks not only presuppose values, but in doing so asks the spectator to become critical of his own values, assumptions, and prejudices. These values are composed into the artwork not only for viewers to appreciate or ‘value’, then, but also to mold values into them, and from them begin to remold even the foundation of society, whose intellectual bases don’t have to be changeless. So, at the same time as it molds culture, art can mold the way society perceives itself, and also shape the way it would like to be perceived in the future. Nevertheless, the comparatively solid ground upon which culture is built is values, even in the everyday sense of the term.

Kasimir Malevich, Taking In The Rye

The Values of Art

Before we go any further we must however dig deeper into what was said about the existence of values within a work of art. Although it may seem clear that values are present in the artist as well as in the spectator, it isn’t necessarily clear that a work of art must necessarily represent such values in itself. Thus it is fair to ask if it is possible that a painting (for example) can be free of any form of values whatsoever. If it is possible, then what I said about values being at the core of art wouldn’t be true. If so, we must then ask ourselves, what then is the foundation of a painting, or indeed any work of art? With this question I only want to say that an aspect of aesthetics is the expression of values – albeit maybe the most fundamental aspect. Therefore we must proceed to ask whether it is possible to have works of art that are devoid of values.

To answer this, let’s begin by asking what exactly happens during the creation process, and if during this process the artist or creator always undertakes a conscious labor.

The first thing that may come to mind, is that many artists use techniques in their work that apply chance as a basic principle, so that the artist might distance herself from societal ˙values, or at least any conscious attempt to manifest them in the artwork. We could say, for example, that a process like that of action painting – as exemplified by Jackson Pollock dripping paint onto canvas – can in no way have completely predictable results, even if the artist tries his or her best to control them (which they often do not).

However, although the technique itself may be random or have unintentional elements, it is still true that the painter never looses intimacy, or better, a bond, with the painting. This word ‘bond’ obviously expresses the closeness that exists between creator and creation, and it would be absurd to think that any such bond can lack all conscious intention. The artwork cannot be completely detached from the artist: the artist can never be an outsider to his own work, for the painting, or any other artwork, as an artistic creation, will in a sense always be nothing more than an extension of the creator.

We can see then that it doesn’t matter what kind of artwork we might be talking about – be it completely realistic, or a painting made by dripping, or even a happening or a performance – the artist can never free himself from his responsibility as a creator. This makes it impossible for him to become an outsider, or a bystander, to his own work. One cannot be a foreigner in one’s own land.

In more precise terms, the artist cannot achieve with his art what many would call ‘objectivity’. Any supposed ‘absolute distance’ between the artist and his work will always rather be by degrees only. He or she may only vary the technique or the intention behind the artwork in order to produce different responses in the spectator; but it is just as impossible for them to be aliens to their work as it is for a mother to be alien to her children (we can even say even more so than that of the mother with her children, for as much as she is involved in the process, the mother does not strictly speaking create her children to be an expression of herself).

This is a very distinct conclusion, for it means that the creative process is non-objective. This means that it is impossible for anyone to describe the artistic creative process through a series of events that have to take place in order for an artistic creation to appear, and hence not generalizable in nature. In common language, there is just no recipe for making art; and not only does such a recipe not exist, it can’t exist. This is one reason why an artist creates while an entrepreneur produces, and why we don’t have factories for paintings as we have for prints.

Furthermore, it is the subjectivity within the work of art that determines the whole significance of the creating. By reflecting upon the necessarily subjective character of the process, we can recognize that what takes place during this process is an encounter of the artist with an inner necessity to express him- or herself. This necessity cannot itself be explained by any tangible need, but only by the artist’s own spiritual reality. This reality is esteemed or ‘valued’ within itself, and also for the values it presents when expressed to others. When we acknowledge this, then a concept like that of Kandinsky’s becomes quite enlightening.

Kasimir Malevich, After The Snowstorm

The Viewer’s Response

We can move now to the perspective of the viewer.

Since we’ve just confirmed the presence of values within the painting, it becomes quite reasonable to say that since we the viewers esteem values, we subsequently esteem and appreciate the painting for its value-charged content, as we can call it.

As we have discussed the importance of spirituality and values, and their relationship with art, it has become clear that in order for a bystander to be able to appreciate art in any form, he must be open not only to the expression of the artist’s unique spirituality – his values and personal aesthetics – he must also be prepared to embrace that reality to some degree. This obviously also implies that what is meant to be conveyed by the artist through his work must actually be understood by the observer! This encounter proposes a communication of sorts, or a mediation, between artist and observer; and this can only take place if the observer is aware of his own spiritual reality and the values it contains. This awareness is most definitely the main condition that must exist not only for the spectator to appreciate the painting that hangs in front of him, but in general, for society as a whole to embrace art as a means to understand and discuss its own values – that is, as a means to conduct a critical appraisal of the place of art in society.

Most important of all, values don’t exist in some oblivious reality that escapes all reach or consequences for practical or daily life. Although it may come across in this way, this is just a result of the same problem. Society as a whole has become so short-sighted that spiritual reality is imagined by many in the same way we imagine fairy tales, as bearing no direct relation to everyday life.

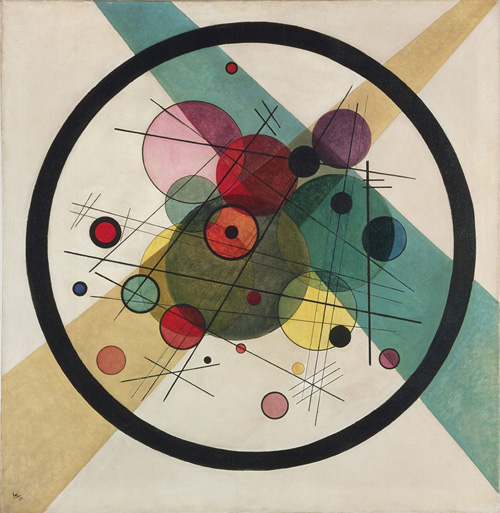

Wassily Kandinsky, Circles In Circle

Conclusion

As a conclusion we must acknowledge that values are present intrinsically in works of art, just by virtue of their being artworks. This however is not to be taken lightly, for it means that the true apprehension of the artist as a creator demands a state of openness on behalf of the viewer (this ‘state of openness’ hints at the ideas of Dilthey, Heidegger and Gadamer). This state of openness is not something that necessarily exists, and may not exist at all if he who observes is not aware of what he’s observing. Of course, an acknowledgement of values as intrinsic to art also sets boundaries for the artist himself, who can only call himself an artist if he accepts his own spirituality or values as the force from which he forges a material expression.

Altogether, even as artistic value continues to reach beyond aesthetic pleasure, it increasingly becomes evident that is a force that enhances and perpetuates the human spirit, and, borrowing Gabriel Marcel’s term, art that deserves to be called art will always give to both maker and observer a sense of fulfilment or completeness. This is what makes it by far the most outstanding expression of the human spirit.

© Daniel Vargas Gómez 2015

Daniel Vargas Gómez is a Doctor in Philosophy from the University of Rotterdam. He currently works on the crossovers between aesthetics, media and culture, from a philosophical perspective.