Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Can The World Learn Wisdom?

Nicholas Maxwell points out where the Enlightenment went wrong.

The crisis of our times is that we have science without wisdom. This is the crisis behind all the others. Population growth; the alarmingly lethal character of modern war and terrorism; vast differences in wealth and power around the globe; the AIDS epidemic; the annihilation of indigenous people, cultures and languages; the impending depletion of natural resources, including the destruction of tropical rain forests and other natural habitats, and the rapid mass extinction of species; pollution of sea, earth and air; and above all, the impending disasters of climate change – all of these relatively recent crises have been made possible by modern science and technology. Indeed, if by the ‘cause’ of an event we mean a prior change that led to that event occurring, then the advent of modern science and technology has caused all these crises. It is not that people became greedier or more wicked in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; nor is the ‘new’ economic system of capitalism responsible, as some historians and economists would have us believe. The crucial factor is the immense success of modern science and technology. This has led to modern medicine and hygiene, to modern high-production agriculture and industry, to population growth, to worldwide travel (which spreads diseases such as AIDS), and to the destructive might of the technology of modern war and terrorism, conventional, chemical, biological, nuclear.

This is to be expected. Science produces knowledge, which facilitates the development of technology, enormously increasing our power to act. It is to be expected that this power will often be used beneficially, as it has been – to cure disease, feed people, and in general enhance the quality of human life. However, in the absence of wisdom, it is also to be expected that such an abrupt, massive increase in power will be used to cause harm, whether unintentionally, as in the case (initially at least) of environmental damage, or intentionally, as in war and terrorism.

Before the advent of modern science, our lack of wisdom did not matter too much, since we lacked the means to do too much damage to ourselves and the planet. But now, in possession of the unprecedented powers bequeathed to us by science, our lack of wisdom has become a menace. The crucial question is: How can we learn to become wiser?

The answer is staring us in the face. And yet it is one that almost everyone overlooks.

The Traditional Enlightenment Programme

Modern science has met with astonishing success in improving our knowledge of the natural world. It is this very success that is the cause of our current problems. But instead of simply blaming science for our troubles, as some are inclined to do, we need, rather, to learn from the success of science. We need to learn from the manner in which science makes progress towards greater knowledge how we can make social progress towards greater wisdom.

This is not a new idea. It goes back to the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, especially the French Enlightenment. Voltaire, Diderot, Condorcet and the other Enlightenment philosophes had the profoundly important idea that it might be possible to learn from scientific progress how to achieve social progress towards an Enlightened world. And they did not just have the idea: they did everything they could to put it into practice. They fought dictatorial power, superstition, bad traditions and injustice, with weapons no more lethal than those of argument and wit. They gave their support to the virtues of tolerance, curiosity, openness to doubt, and readiness to learn from criticism and experience. Courageously and energetically they laboured to promote reason in personal and social life. And in doing so, in a sense they created the modern world, with all its glories and disasters.

The philosophes of the Enlightenment had their hearts in the right place. But in intellectually developing the basic Enlightenment idea, unfortunately, they blundered. They botched the job. And it is this that we are suffering from today.

If it is important to acquire knowledge of natural phenomena to better the lot of mankind, as Francis Bacon had insisted, then it must be even more important to acquire knowledge of social phenomena, or so the philosophes thought. And they thought that the way to learn how to do this would be to develop the social sciences alongside the natural sciences using similar methods. First, social knowledge must be acquired; then it can be applied to help solve social problems. So they set about creating and developing the social sciences: economics, psychology, anthropology, history, sociology, political science.

This project was immensely influential, despite being damagingly defective. It was developed throughout the nineteenth century by men such as Saint-Simone, Comte, Marx, J.S. Mill and many others. Then, with the creation of departments of the social sciences in universities all over the world in the first part of the twentieth century, it was built into the institutional structure of academic inquiry. Academic inquiry today, devoted primarily to the pursuit of knowledge and technological know-how, is the outcome of two past revolutions, then: the scientific revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which led to the development of modern natural science; and the later equally important but seriously defective Enlightenment revolution. This results in the urgent need to bring about a third revolution; to put right the structural defects we have inherited from the Enlightenment.

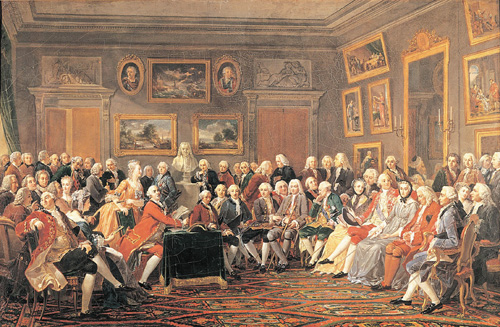

The philosophes meet to discuss the Encyclopedia

Three Things To Get Right

But what, it may be asked, is wrong with the traditional Enlightenment programme?

Almost everything. In order to implement properly the basic Enlightenment idea of learning how to achieve social progress from scientific progress, it is essential to get the following three things right:

1. The progress-achieving methods of science need to be correctly identified.

2. These methods need to be correctly generalised so that they may be fruitfully applied to any worthwhile problematic human endeavour, whatever its aims may be, and not just applicable to the one endeavour of acquiring knowledge.

3. The correctly generalised progress-achieving methods then need to be exploited correctly in the great endeavour of trying to make social progress towards an enlightened, wise world.

Unfortunately, the philosophes of the Enlightenment got all three points wrong, and as a result their blunders, undetected and uncorrected, are built into academia as it exists today.

The Errors of Standard Empiricism

First, the philosophes failed to capture correctly the progress-achieving methods of natural science.

From D’Alembert in the eighteenth century to Popper in the twentieth, the view most widely held amongst both scientists and philosophers has been, and continues to be, that science proceeds by assessing theories impartially in the light of evidence. The assumption is that no thesis about the world is accepted permanently by science independently of evidence. But this standard empiricist view is untenable. If taken seriously, it would bring science to a standstill. For given any accepted scientific theory – Newton’s theory of gravitational attraction, say – endlessly many rival theories can be concocted which agree with it about observed phenomena, but disagree arbitrarily about yet-unobserved phenomena. For instance, some rival theory of gravitation might predict elliptical orbits for planets in our solar system, but triangular orbits for unobservable star systems in distant galaxies. If empirical considerations alone determined which theories are accepted and which rejected, then science would be drowned in an ocean of such empirically successful rival theories. In practice, however, these rival theories are excluded because they are disastrously disunified. Two major considerations govern acceptance of theories in science: empirical success and unity.

What does it mean to say that a physical theory is unified? It means that the content of the theory – what the theory asserts about the world – is the same for all the vast range of actual and possible phenomena to which the theory applies. For instance, if Newton’s inverse square law for gravity applies in our star system, it must apply in all star systems. In contrast, a disunified theory asserts that one set of laws apply to one range of phenomena, a different set of laws for another range, and so on. The greater the number of different sets of laws, the greater the disunity of the theory.

The laws of a theory may differ in different ways, some ways being more serious to the theory’s unity than others. Thus, Newton’s law of gravitation might change in time. In ten years time, gravity might abruptly become a repulsive force, or it might change in certain regions of space, or for objects at a certain distance from one another, or for objects of a specific mass and constitution. One disunified version might assert that Newton’s inverse square law, which says that the gravitational attraction between masses is inversely proportional to the square of their distance from each other, holds for all objects everywhere, except for spheres made of gold with masses greater than 1,000 tons moving in space no more than 1,000 miles apart, when an inverse cube law of gravitation holds. In my book Is Science Neurotic? (Imperial College Press, 2004), I argue that eight different kinds of disunity can be distinguished. All, however, exemplify the same basic notion: that a theory is disunified precisely to the extent that it has different sets of laws applying in different circumstances. For perfect unity, what the theory in question asserts must be the same for all actual and possible phenomena to which the theory applies. (For more detailed accounts of this notion of unity, see Is Science Neurotic?, plus my The Comprehensibility of the Universe, OUP 1998, and ‘Has Science Established that the Cosmos is Physically Comprehensible?’, available at philpapers.org/rec/MAXHSE.)

Given any accepted physical theory, more or less unified, there will always be endlessly many grossly disunified rivals even more empirically successful than the original, which may be concocted by accounting for new observations by tacking ad hoc qualifications onto the original theory. But none of these endlessly many empirically more successful ad hoc disunified rivals is ever seriously considered in scientific practice. They are all ignored because, although being more empirically successful, they hopelessly fail to satisfy the crucial requirement of unity.

The Method of Scientific Progress

Now comes the decisive step in the argument. In persistently accepting unified theories, and never even considering disunified rivals that are at least as empirically successful, science makes a big persistent assumption about the universe. Science assumes that the universe is such that all grossly disunified theories are false, i.e., that the universe has some kind of unified structure. This means that it is comprehensible, in the sense that physical explanations for phenomena exist to be discovered – only more or less unified theories being explanatory.

But the metaphysical (and thus untestable) assumption that the universe is comprehensible is profoundly problematic. Science is obliged to assume, but does not know, that the universe is comprehensible. Much less does it know that the universe is comprehensible in this or that specific way. Moreover, a glance at the history of physics reveals that ideas about how the universe may be comprehensible have changed dramatically. In the seventeenth century the idea was that the universe consists of corpuscles – minute billiard balls – which interact only by physical contact. This gave way to the idea that the universe consists of point-particles surrounded by symmetrical fields of force. This in turn gave way to the idea that there is one unified self-interacting field varying smoothly throughout space and time. Nowadays we have the idea that everything is made up of minute quantum strings embedded in ten or eleven dimensions of space-time. Some kind of assumption about the nature of physical reality must be made, but, given the historical record, and given that any such assumption concerns the ultimate nature of the universe – that of which we are most ignorant – it is only reasonable to conclude that it is almost bound to be false.

One way to overcome the fundamental dilemma inherent in the scientific enterprise of having to assume that the universe is comprehensible, is to construe science as making a hierarchy of assumptions concerning the comprehensibility and knowability of the universe, these assumptions asserting less and less as one goes up the hierarchy, thus becoming more and more likely to be true, and more and more such that their truth is required for science, or the pursuit of knowledge, to be possible at all.

At the top of the hierarchy we have the assumption that the universe is such that we can acquire some knowledge of our local circumstances. If this assumption is false, we can gain no knowledge, whatever we assume. We are never, in any circumstances whatsoever, going to want to or need to reject this assumption, even though we have no reasons to suppose that it is true.

As we descend the hierarchy, assumptions become increasingly substantial, and so increasingly likely to be false. One assumption is that the universe is comprehensible in some way or other. There is something – God, cosmic purpose, a cosmic programme, or a physical entity – present at all times in all phenomena, which in some sense determines how things are and what goes on, and in terms of which all phenomena can, in principle, be explained and understood. Next down the hierarchy is the assumption that the universe is physically comprehensible: the universe is such that some true, unified physical ‘theory of everything’ exists to be discovered, in terms of which all physical phenomena can, in principle, be explained. Next down, is an even more specific, substantial assumption, about the nature of the entities postulated by the ‘theory of everything’: that the physical world is made of corpuscles, point-particles, a unified field, quantum strings, or whatever form the building-blocks of everything eventually turns out to take.

In this way a framework of relatively insubstantial, unproblematic, fixed assumptions and associated methods is created at the top of the hierarchy, below which increasingly substantial and problematic assumptions and associated methods can be changed and indeed improved as scientific knowledge improves. Put another way, a framework of relatively unspecific, unproblematic, fixed aims and methods is created below which much more specific and problematic aims and methods evolve as scientific knowledge evolves. There is positive feedback between improving knowledge and improving aims and methods, improving knowledge about how to improve knowledge. In this way, science adapts its own nature to what it discovers about the nature of the universe.

This is the methodological key to the unprecedented success of science. It is therefore in terms of this hierarchical, aim-oriented empiricist conception of science that we need to conceive of the progress-achieving methods of science. In failing to construe science in this way, the Enlightenment committed its first blunder.

The 2nd and 3rd Blunders of the Enlightenment

Having failed to identify the methods of science correctly, the philosophes naturally failed to generalise these methods correctly. Specifically, they failed to appreciate that the idea of representing the problematic aims and associated methods of science in the form of a hierarchy can be generalised and applied fruitfully to other worthwhile enterprises besides science. Many other enterprises with problematic aims would benefit from employing a hierarchical methodology generalised from that of science, thus making it possible to improve their own aims and methods as the enterprise proceeds. There is the hope that in this way, some of the astonishing success of science might be exported into other worthwhile endeavours with quite different aims.

Third, and most disastrously of all, the philosophes completely failed to apply such generalised progress-achieving methods to the immense and profoundly problematic task of making social progress towards an enlightened, wise world. The aim of such an enterprise is notoriously problematic. For all sorts of reasons, what constitutes a good world, an enlightened, wise or civilised world, attainable and genuinely desirable, must be inherently and permanently problematic. So here above all, it is essential to employ a generalised version of the progress-achieving methods of science, designed specifically to facilitate progress when basic aims are problematic.

How To Create A Wise Society

In short, properly implementing the Enlightenment idea of learning from scientific progress how to achieve social progress towards an enlightened world would involve developing social inquiry primarily as social methodology, not primarily as social science. A basic task would be to get progress-achieving methods, generalized from those of science, into personal and social life, so that actions, policies and ways of life may be developed and assessed in life somewhat as theories are assessed in science. The task would be to get these methods, designed to improve problematic aims, into other institutions besides science – into government, industry, agriculture, commerce, the media, law, education, international relations. A basic task for academic inquiry would be to help humanity learn how to resolve its conflicts and problems of living in more just, cooperatively rational ways than at present. This task would be intellectually more fundamental than the scientific task of acquiring knowledge. Social inquiry would be intellectually more fundamental than physics. Academic thought would be pursued as a specialised, subordinate part of what is really important and fundamental: the thinking that goes on, individually, socially and institutionally, in the social world, guiding individual, social and institutional actions and life. The fundamental intellectual and humanitarian aim of inquiry would be to help humanity acquire wisdom – wisdom being the capacity to realise, that is, apprehend and create, what is of value in life, for oneself and for others. Wisdom thus includes knowledge and technological know-how, but much else besides.

Academia would seek to learn from, educate, and argue with the world beyond it, but it would not dictate. Ideally, academia would have sufficient power (but no more) to retain its independence from government, industry, the press, public opinion, and other centres of power and influence. If it pursues this course, academia would become a kind of people’s civil service, doing openly for the public what actual civil services are supposed to do in secret for governments. Academia would seek to help humanity realize what is of value in life by intellectual, technological and educational means.

One important consequence flows from the point that the basic aim of inquiry would be to help us discover what is of value, namely that our feelings and desires would have a vital rational role to play within the intellectual domain of inquiry. If we are to discover for ourselves what is of value, then we must attend to our feelings and desires. But not everything that feels good is good, and not everything that we desire is desirable. Rationality requires that feelings and desires take fact, knowledge and logic into account, just as it requires that priorities for scientific research take feelings and desires into account. In insisting on this kind of interplay between feelings and desires on the one hand, and knowledge and understanding on the other, the conception of inquiry that we are considering resolves the conflict between Rationalism and Romanticism, and helps us to acquire what we need if we are to contribute to building civilization: mindful hearts and heartfelt minds.

If the Enlightenment revolution had been carried through properly, the three steps indicated above being correctly implemented, the outcome would have been a kind of academic inquiry very different from what we have at present. We would possess what we so urgently need, and at present so dangerously and destructively lack: institutions of learning well-designed from the standpoint of helping us create a better, wiser world.

© Nicholas Maxwell 2015

Nicholas Maxwell, Emeritus Reader in Philosophy of Science at University College London, is the author of How Universities Can Help Create a Wiser World: The Urgent Need for an Academic Revolution, published by Imprint Academic. For more, see www.ucl.ac.uk/from-knowledge-to-wisdom.