Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Emotion and Imagination by Adam Morton

Don Berry probes the connection between Emotion and Imagination.

What is an emotion, and what is its connection to imagination? Adam Morton, a philosophy professor at the University of British Columbia, gives us a surprising answer.

First, an emotion is a state we can enter into where pressure is generated towards our having certain kinds of thoughts centred on a particular theme. For instance, if a manager is seriously displeased with one of her subordinates and feels anger, she may think over various scenarios, such as berating or firing them, or otherwise humiliating them in some way. Some of these possibilities may later be acted on, some may be entirely fanciful; but they are all developed from a particular perspective that regards the wayward employee in a certain light. Emotions must therefore be directed towards a specific person or object – sharply distinguishing them from moods, which are more general collections of characteristic feelings that we move between.

An essential connection between emotion and imagination follows naturally from the broad definition Morton gives to imagination – which is the faculty of mentally representing a possibility in a purposeful way. The degree of vividness of the experience is not relevant here: I could indeed be provoked to have a detailed flashback of a scene from my childhood that seemed rich in detail and almost real, but on this definition this would not count as a case of imagining unless there was some specific purpose to my reminiscing. Conversely, we can talk about a mouse imagining the possibility of a cat nearby if the mouse takes sensible precautions based on this contingency, although this may be achieved without the usage of mental imagery, or even without the mouse having any conscious experience of the representation. Under these definitions, emotion certainly involves the capacity for imagination, then, because an emotion is defined as a kind of state where we experience a pressure towards generating imaginative representations of possibilities with regard to some specific object.

Another way in which emotions depend on imagination is that certain emotions, such as embarrassment, require us to imagine ourselves being perceived from an external perspective. Morton focuses on a connected family of moral emotions: shame, guilt, regret and remorse. One way that they can be distinguished is by the nature of the representations they generate: guilt primarily takes as its object some specific action, whereas with shame the focus is on our character as a whole. But the differences between the various members of this family can also be understood by considering the nature of the external perspective that structures them, our attitude towards them, or the attitude of the imagined observer towards us. Remorse, for instance – the most serious of these emotions – is concerned with our harming others with whom we now empathise; and we imagine the other person(s) as appealing to our mercy, perhaps imploring us not to carry out some malign action. With guilt, however, the external point of view is one of anger directed towards us for the breach of some rule of conduct; this is regarded by us with fear (another emotion); and this guilty fear is directed towards anticipation of the future consequences of our actions rather than at what harm we may have caused in the past. This variety of embedded perspectives and complex interplay is part of what allows us to have such a wide and nuanced range of emotional states.

Two views of Phineas Gage and his spike

Gage’s Splitting Headache © JD Van Horn, A Irinia, CM Torgerson, MC Chambers, R Kikinis, et al., 2012

Philosophy & Psychology

This book clearly owes an immense debt to recent work in cognitive science, where many of these themes have been developed. Morton rarely refers to specific experiments; however, the important results and consensus positions are woven seamlessly into the narrative, or implicitly in place in the background of the discussion.

Some of the empirical work he does directly discuss is eminently interesting. One infamous case study he mentions is Phineas Gage, an American construction worker who received an unusual kind of brain damage while working on a railway in 1848. Whilst using a long metal pole to pack gunpowder into an hole, the gunpowder exploded, causing the pole to shoot through his skull via his jaw and straight out the top of his head, landing some eighty feet away. Miraculously, Gage not only survived but appeared to have his motor, cognitive and linguistic functions intact. However, a part of the right frontal lobe of his brain, above his eye, associated with integrating planning with socially-appropriate emotions, was destroyed. Over the next decade or so his friendships and career fell apart, and his life sank into disarray. This unfortunate story ultimately led to a host of new insights about the role of emotions in structuring our long-term plans and actions, some of which Morton puts to work in this text.

One possible drawback of Morton’s empirically-based approach is that his more purely analytical readers, in R.G. Collingwood’s sense, must suffer a lack of intellectual autonomy: we simply have no direct way of telling whether some of his claims are true or false. Some of the results he makes use of appear to be fairly well established; for instance, the systematic biases inherent in our introspective analyses of the causes of our own behaviour. But there are others that may be less well established, seriously contested, or the subject of current controversy, and it’s often not clear which is which. Moreover, even a result accepted as orthodoxy could be a mere assumption of a contemporary paradigm rather than something that has been firmly established.

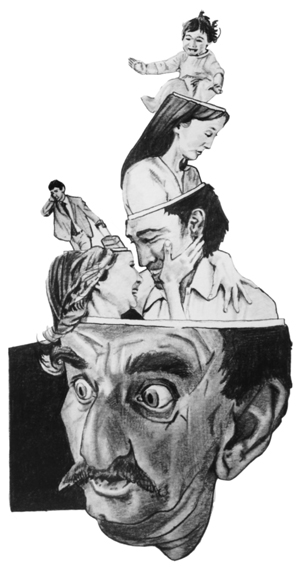

A Russian Doll Imagination by Peter Pullen

Please visit peterpullen.weebly.com

Morton’s findings also raise the question: is it right to separate moral philosophy from moral psychology? The book shows that what are often studied as separate phenomena by philosophers – emotion and imagination, feeling and thinking, or planning and action – can sometimes turn out to be different aspects of the same underlying processes. Besides, moral philosophy itself presupposes some account of agents’ relations to their intentions, reasons, and indeed emotions. Perhaps familiarity with the psychological literature will turn out to be something no moral philosopher can do without, then. Combining the two disciplines certainly has impressive precedents; no less a figure than Aristotle tended to treat them as far more intimately connected in his works than is typical today.

Those lacking a background in psychology should not be put off, however. Although some trust in Morton’s judgement is certainly required, he points out in the preface that the book is “clearly more philosophy than psychology.” But it’s perhaps not philosophy as we know it from the work of most other contemporary practitioners. Rather than focusing on clear definitions supported by conceptual analysis and rigorous rational argument, Morton typically proceeds by asking us to imagine possibilities, or by recounting a number of illustrative stories, and, in general, by appealing to our emotions. Sometimes he simply confidently asserts opinions from introspective insight that will not be shared by everyone. For example, he complains, “think how we are annoyed by people who are too quickly familiar with us, especially younger strangers.” However, in his own way, his approach reminds me of the later Wittgenstein: continually going back to the same problems and approaching them from multiple directions with examples drawn from everyday life.

However, this book may come across as disappointing to some philosophers – particularly those whose conception of an ideal philosophical work is a sustained argument developing and defending a single complex thesis. Indeed, the book was born out of a collection of papers dealing with a loosely-structured collection of themes, and it certainly bears the marks of its origin. However, a book does us a service if it provides us with information and ideas that help us to understand its subject matter, or even if it just raises our awareness of the interesting questions. Moreover, which approach is best depends in part on what we are trying to achieve philosophically. To his credit, Morton does consider this issue, and he makes it clear that his goal is not to create a body of descriptive or metaphysical truths; rather, as he states in the closing sections, the book is motivated by a set of practical problems. Morton feels that most of us are in fact hopelessly confused in our emotional lives: we misunderstand the sources of our moral emotions, we fail to question their authority, and we often succumb to one member of the emotion family when another of its cousins would be more appropriate or effective. The reason for his rhetorical strategy is clear, then: his own research on the way emotion is central to thought suggests that people in general will be persuaded more by this approach. It is also only with vivid examples that Morton can attempt to provide us with the tools we need to deal with the often hidden practical problems his book highlights, and to which it aims to serve as a corrective.

© Don Berry 2015

Don Berry is an aspiring philosopher and PhD student at University College, London. In his spare time he paints and teaches mathematics and science.

• Emotion and Imagination, by Adam Morton, Polity, 2013, 184 pages, £14.99, ISBN: 978-0745649580