Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Clueless

Susan Hopkins isn’t clueless about feminism’s Nietzsche.

The 1990s marked the ascendancy of postmodernism and poststructuralism across pop and politics as well as in academic theorising. This was a time when Madonna’s ‘blonde ambition’ pop was reinterpreted by third wave feminists as a political act; and when ‘clueless’ heroines in teen movies could reference everything from television infomercials to classic literature. Philosophy too, to some extent, was absorbed and repurposed by pop postmodernism. Pop culture frequently parodied earnest pseudo-intellectual types by, for example, portraying them reading Nietzsche. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) is, after all, one of the best-known and most widely misappropriated of nineteenth century philosophers. A more surprising turn in 90s culture was the third wave feminist adoption of Nietzsche in political theorising.

At first glance, Nietzsche seems an unlikely feminist. Concerning his attitude to women, he is better known for his infamous quip from Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1885): “Are you visiting women? Do not forget the whip!” However, Nietzsche’s quirky posthumous pop-ups in both pop culture and politics illustrate some of the interesting complexities and contradictions of our postmodern age. One scene in particular in the cult-classic teen comedy Clueless (1995) brings together the beautiful mess that was Nietzsche, femininity and feminism in the 1990s.

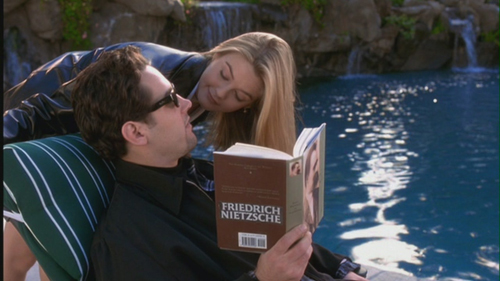

Clueless, an American film written and directed by Amy Heckerling based loosely on Jane Austen’s Emma, turned twenty this year. Like many women who were young in the 1990s, I can clearly recall my favourite quotes and scenes from this ultimate chick flick two decades on – in part because the film both celebrates and pokes fun at an unapologetic hyper-femininity and hyper-mediated girl culture. Its comic charm derives from the contradiction that despite the fact that the film’s lead character, Cherilyn ‘Cher’ Horowitz (Alicia Silverstone), is vacuous, ill-informed, superficial, obsessed with appearances, and stereotypically feminine, she is the most lucky and likeable character in the film. In contrast to her well-read ex-stepbrother love interest Josh (Paul Rudd), who thinks deeply, Cher seems to skate lightly along the surface of things, and thus things seem to go her way. In keeping with the ‘opposites attract’ trope of romantic comedy, Josh is an earnest, socially responsible and self-conscious CNN-watching, university-station-listening, granola-eating environmentalist scholar who takes himself too seriously. He first appears as the very image of the morose young man in black jeans, goatee and dark glasses, reading Nietzsche as he lounges poolside in Beverly Hills. So the film’s first impressions of Josh establish him as the sensitive, self-conscious and privileged ‘college boy’ stereotype, and this archetypically postmodern moment also transports dark Nietzschean literature into a sunny American Dream.

Cher and Josh philosophise

Still from Clueless © Paramount Pictures 1995

The Chick Flick Feminist Backlash

Clueless is a light-hearted but razor-sharp look at a contemporary culture overfull of counterfeits, confusion and contradiction. There is no ‘outside’ to this culture anymore, for even adolescent ennui is seamlessly appropriated and absorbed by Hollywood fictions in a Clueless sort of way.

Clueless also captures a particular moment in pop and politics for the class of’95. From a traditional or second wave feminist viewpoint, the main female characters of Clueless – Cher, Dionne and Tai – are an embarrassing disappointment to feminism, since they’re obsessed with fashion, make up and frivolous femininity. More concerned with shopping than politics, the Clueless girls define themselves and others by their appearances and patterns of consumption. A long way from the idealism of the ‘make love not war’ generation, Cher is privileged, naïve and somewhat conservative, or as Tai (Britanny Murphy) wryly observes, “a virgin who can’t drive.” But although hardly revolutionary, Cher is no sexual doormat either: “I’m not a prude. I’m just highly selective. Well, you see how picky I am about my shoes, and they only go on my feet.” As a ‘dumb blonde’ female stereotype, Cher is also dropped into a very self-referential or ‘knowing’ postmodern teen culture. She may know virtually nothing about ‘what’s really going on in the world’, but her sassy wisecracks reveal a rich knowledge of pop culture history.

Reflecting the rise of third wave feminism in the 1990s, the new Clueless-style chick flicks suggested it was possible to embrace aspects of traditional ‘girlie-girl’ femininity and still be strong, ambitious, and empowered. This celebration of girl culture was in some sense a backlash against the more traditional and serious style of feminism championed by second wave activists of the 60s and 70s. The new ‘girl power feminists’ railed against the perceived limitations imposed by their second wave mothers and teachers and resisted the established definitions of what was ‘good’ (that is, empowering) and ‘bad’ (oppressive) for them, to reclaim the pleasures of femininity. So although Josh dismisses Cher’s pursuits as manipulative, trivial and superficial, Cher will not give up the girl-culture pleasures of, for example, the makeover, because it is an opportunity to strengthen female friendships. For Cher these are not ‘guilty pleasures’, since her postmodern, postfeminist generation embraces hyper-femininity in an unabashed, self-aware and ironic fashion. As Cher’s best friend puts it: “Cher’s main thrill in life is a makeover: it gives her a sense of control in a world full of chaos.”

A particularly postfeminist moment in Clueless occurs when Cher manipulates a teacher into changing her grades: “I told my PE teacher an evil male had broken my heart, so she raised my C to a B.” In the privileged world of girls like Cher, the idea of an evil overarching patriarchy is apparently laughable. The uneasy adolescent humour here comes at the expense of adult second wave feminists. In Clueless, feminism is positioned not as a truth, but as just another story or discourse that Cher manipulates to suit her own interests. The light-hearted banter indicates the individualistic or fragmented bent of 90s feminist practices, or as Cher would say, “It’s a personal choice every woman has got to make for herself.”

Nietzsche’s Feminist Makeover

Around the same time, Nietzsche was getting a makeover within the academy.

In simpler times, Nietzsche would have been dismissed by feminists as an elitist misogynist with a history of relationship troubles. His frequent distinctions between ‘the masculine’ and ‘the feminine’ would themselves have been dismissed as a primitive biological determinism. More recently however, a new style of feminist political theory has suggested that we should not take Nietzsche too literally, but rather recognise his provocative metaphors as conceptual tools for questioning power, morality, and even gender. Nietzsche’s ‘revaluation of all values’ in Beyond Good and Evil (1886), for example, can support the most radical of feminist thinkers, who question whether ‘woman’ as a category even exists beyond theory-fiction.

Poststructural feminists follow Nietzsche in attacking the Enlightenment’s faith in universal morality. Nietzsche says that there is no grand truth waiting to be uncovered, only competing fictions. Moreover, political truth-claims are always a form of violence or ‘imposition of one’s own forms’ on others. From such a Nietzschean standpoint, moral-political doctrines such as feminism, when they are imposed as another form of control or regulation, offer less, not more power to their subjects. Some third wave feminists have also adopted these ideas to identify the moral-political impositions in traditional critiques of girl culture. The decision to classify certain texts as ‘right and proper’ whilst regarding others as ‘dangerous and oppressive’ is, after all, a moral decision, and so another form of regulation. In other words, judgments about culture are another way young women are controlled, both by men and by other women. One woman’s empowerment can be another woman’s oppression.

So Nietzsche’s contrast between ‘aesthetic’ and ‘moral’ ways of thinking provides a conceptual tool to take apart different ways of looking at feminism and femininity. However, a moralistic interpretation lacks a feeling for the humor, complexity and reflexivity of postmodern culture. This is why a ‘third way’ to respond to Nietzsche’s work is necessary in a postmodern world.

It’s ironic that the spectre of Nietzsche at the poolside is used in Clueless to signal that Josh is a serious scholar and an aspiring intellectual, because Cher’s choice of style over substance – or rather, style as its own substance – is the more Nietzschean move. Cher may well be superficial or ‘fake’; but as Nietzsche would suggest, a preference for the ‘real’ over the ‘fake’ is nothing more than a moral prejudice. Josh also represents the long-held but erroneous assumption that the world can be conquered through reason and rationality. For Nietzsche this is a ‘masculine’ folly.

These Nietzschean insights are relevant and timely. Certainly in postmodern times, the world is rarely considered to be reasonable or rational. Instead, our increasingly mediated culture speaks in the language of images, appearances and illusions. Much second wave feminism and academic discourse is built on the faith in truth and a fear of images: it has invested in the belief that it’s possible to separate out the real from the fake and simulated. But postmodern feminism, like Nietzsche, doesn’t think it is possible.

Nietzsche’s Feminine Sides

Just as third wave feminism has reclaimed the celebratory and fun aspects of girlie culture, Nietzschean feminists have used Nietzsche to put the feminine back into philosophy. This includes celebrating what Nietzsche in Beyond Good and Evil regards as the eternal feminine: “From the beginning, nothing has been more alien, repugnant, and hostile to woman than truth – her great art is the lie, her highest concern is mere appearance and beauty.” So for Nietzsche the eternal feminine is only concerned with image, and that is her strength; she is to be praised for her attention to appearances. For Nietzsche, ‘emancipation’ robs women of the greater power of the symbolic realm, and entry into the realm of reason is entry into a weaker, corrupted or ‘masculine’ realm. So although Josh admonishes her for her ‘feminine’ concern with shiny surfaces, Cher is unimpressed with his ‘masculine’ claims to reason and rationality. Again, as Nietzsche would say, the preference for depth over surface is nothing more than a moral prejudice; it is misguided because there is no universal truth, and no true self – there are only the fictions, the stories that we create. These stories in turn make us who we are. As Nietzsche suggested in the Genealogy of Morals (1887), “‘the doer’ is merely a fiction added to the deed.” The implications of this for feminism are powerful because Nietzschean analysis also suggests that gender itself is a fiction – that is, something that can be made, and thus made-over. Traditional feminism was based on an assumption of woman’s true self, but poststructuralist feminism focuses on the multiple ways of experiencing and playing with feminine fictions. For poststructuralist feminists influenced by Nietzsche, gender is a performance, a dramatic effect, rather than a cause. Like truth, the self is invented rather than discovered. A feminist following Nietzsche might therefore celebrate the makeover, that is, embrace the art of self-invention and re-invention. As Nietzsche suggests, we should not seek to strip back illusion in search of reality, but rather enjoy the multiple, messy fictions which make up our identity and our world.

© Dr Susan Hopkins 2015

Susan Hopkins is a writer, and a lecturer at the University of Southern Queensland.