Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Science & Morality

Science & Philosophy: A Beautiful Friendship

Amy Cools reminds us why science needs philosophy.

There’s been some very public dig-taking between the science and philosophy camps lately. Lawrence Krauss, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, Stephen Hawking, and other scientists are saying philosophy’s become irrelevant, little more than an esoteric Old Boy’s Club. On the other hand, philosophers, theologians, politicians and others criticize ‘scientism’, the conviction that science, and only science, can and should be the source for all human knowledge; that all truth claims – that all ethical, metaphysical, and political beliefs – should not only be informed by or founded on, but entirely determined by, empirical evidence.

Michael Shermer doesn’t dismiss philosophy so directly in his article ‘A Moral Starting Point: How Science Can Inform Ethics’ (Scientific American, February 2015). He includes philosophy alongside religion and political theory as arenas of thought in which people seek answers in matters of right and wrong, good and evil. However, Shermer says science can provide those answers, and he goes on to explain why he believes ethics has no better source than science. The history of the human race is rife with slavery, torture, theft, and discrimination, and all diminish human flourishing. Much of this harmful behavior consists of a group abusing certain of its members for the sake of others. But since it’s individual beings that “perceive, emote, respond, love, feel, and suffer” Shermer says, it’s individual beings that are the fundamental units of nature – evidenced by the fact they’re what natural selection targets. The primary purpose of ethics, then, is to promote the flourishing – including the survival and reproduction – of individual beings, and to denounce all that doesn’t.

Yet as I read Shermer’s article I found I have some philosophical objections. For instance, I worry that Shermer’s argument helps perpetuate a myth widely maintained by those who feel the need to erect walls around their respective fields of inquiry, that there’s a sharp dividing line between each field of inquiry. Thus when Shermer includes philosophy in the list of alternate sources for ethics, and by preferring science implicitly dismisses it as the best candidate, I think that he hints, wrongly, that philosophy is in competition with science.

The Problems of Deriving Ethics From Brute Facts

The application of science is never ethically neutral

A more central problem is that, like others in seeking a scientific account of morality, Shermer doesn’t discuss how easy it is to jump to ethical conclusions – to infer an ‘ought’ too quickly from an ‘is’. Philosopher David Hume is famous for describing how tricky it is to derive ‘ought’ directly from ‘is’, or in other words, how tricky it is to logically demonstrate why something is a certain way means things should be a specified way, or things should be done in a certain way (A Treatise of Human Nature, Book III: Of Morals,1739). For example (not Hume’s argument): how do we go about deciding that one fact – one ‘is’ – is more important than another fact when determining what ought to be done?

A famous example of leaping too quickly from the ‘is’ to the ‘ought’– or in other words, deriving an ethical system too quickly from a scientific discovery – is eugenics. Many Victorian-era scientists and philosophers were so enthusiastic about the thrilling new scientific theory of natural selection that they thought it could be applied to everything. So just as it’s a fact that based on the ability to thrive in its environment, nature selects for or against individual organisms, these thinkers thought that human beings should also act as arbiters of fitness. Thus from the late Nineteenth Century to the middle of the Twentieth, many scientists thought that the human species should be ‘perfected’ through the judicious selection of traits to pass on to future generations. In other words, they thought they should select against those individuals possessed of supposedly ‘undesirable’ qualities – ‘selection’ in this case meaning sterilizing or killing.

Here, philosophy and science (and yes, even religion) could clearly have worked together better. Arguably these eugenic ethicists could have used a lot more Hume (philosopher) and a little less Cesare Lombroso (physician and criminologist, who thought all bad human traits were physically inherited). It’s not that the physical sciences should not contribute to ethics; it’s that more checks and balances between the fields of inquiry and more good arguments from philosophers could have kept many over-eager biologists from misapplying their discoveries. For instance, if eugenicist scientists had paid more heed to Hume’s warning that we can’t so readily derive an ought from an is, they might have done a better job of including all available scientific data in their social theories, and more carefully considered all the evidence, including human moral instincts and ethical arguments in favor of human equality, and so restrained themselves from unleashing such a destructive ideology on the world.

But shouldn’t ethics be informed by facts? If it isn’t, doesn’t that make ethics too arbitrary or abstract to be applied to the lives of actual living human beings? Like Shermer, I certainly think that it should. But contrary to Shermer and his peers, I also think that empirically-observable facts aren’t enough on their own to determine what we ought to do. In fact, such facts can’t be enough all on their own, because, for one thing, there are so many facts to consider – too many variables – many of which separately indicate opposing courses of action. To return to one of the many problems with eugenics: its promoters considered the ‘is’ of natural selection against so-called ‘unfit’ members of society as the most important fact to consider in deciding which lives society ought to consider worth living. After all – as that Western elite believed – selection against weak and ecologically ‘unfit’ individuals had made their descendants – ie, them – ‘superior’. But there are other relevant facts to consider: for example, human beings are naturally disposed to empathize with those who are suffering, to help them even if they are sickly, disabled, or otherwise more susceptible to natural deselection. This empathic instinct is itself an evolved trait. It’s also a fact that this set of cooperative instincts that compels us help the ‘unfit’ survive drives us to help each other live happier, healthier, wealthier, and therefore in the long run ‘fitter’ lives, as individuals, and as members of society.

The Group Interests of Individuals

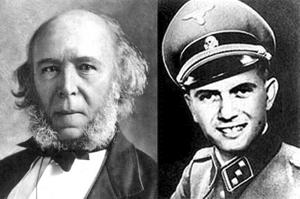

Warnings from science’s recent history: Herbert Spencer, Originator of ‘Social Darwinism’, and Josef Mengele, Nazi doctor at Auschwitz

Shermer argues that the well-being of individuals has been scientifically demonstrated to be the primary goal of ethics. As he explains, “The first principle of the survival and flourishing of sentient beings is grounded in the biological fact that it is the discrete organism that is the main target of natural selection and social evolution, not the group. We are a social species, but we are first and foremost individuals within social groups and therefore ought not to be subservient to the collective.” However, it’s not so clear that he’s justified by the scientifically-confirmed facts alone in saying that because natural selection works on the individual, it’s the individual whose interests should be protected first, and society second. After all, natural selection also works against individuals, culling some, resulting eventually in the genetic benefit of the group. So one could just as well argue that the evidence shows that it’s better for individuals, as well as for society, if those who are sickly or more likely to pass on disease or disability to others, should be allowed to die off the way that nature would have it, without our intervention. Of course, I’m emphatically not arguing that: rather, I’m making the point that a ‘scientific’ ethicist such as Shermer needs more than just an array of facts to show why some facts and not others should inform ethics; he needs an interpretation of those facts as informed by ethical argument.

It’s true that historically, far too much death and destruction have been wrought on individuals when they’re perceived as ‘subservient’ to the group. In this, Shermer has much evidence on his side. But it’s also true that much harm results from placing too much emphasis on the rights of individuals over the well-being of society. Lax gun regulations make it easy for gun enthusiasts to enjoy their hobby, but also make it easy for the murderously criminal and dangerously mentally ill to obtain guns too; or, liberal labor laws make it too easy for employers to exploit and abuse their workers, to the point of disabling injury and death; lax financial regulations allow a few speculators to plunge economies into ruin and populations into a state of want; ‘personal belief’ exemptions allow parents not to vaccinate their children, sometimes resulting in epidemics – the list goes on and on.

Moreover, in our intensely social, emotive, thinking human species, the incredible degree of individuality that individuals can achieve is due as much to the contributions of the group over time as to the individual’s own efforts. Human beings make art, tell stories, build buildings and erect monuments, and create such rich and complex products of thought as history, myth, religion, politics, literature, science, and to my mind the greatest (since it overarches and unifies all other systems of thought), philosophy; and we can do so precisely because of the level of sociability we have evolved. The rugged, self-reliant individual of American mythology is precisely that: a myth. No human being could get very far if they didn’t have a society helping educate, feed, clothe, and equip them with the tools and technology they need to perform their wonderful individual feats, to restore them to health, and to pass on their story afterwards.

Therefore, people flourish when individuals’ efforts are promoted and when they’re not allowed to infringe too much on the interests of the group. The human species, as a whole, flourishes so well just because of this two-way dependence between the individual and the group: you can’t have one without the other. The incredible diversity of individuals should be encouraged and protected because they make our species among the most adaptable, and therefore the most resilient, on earth. When we oppress individuals – when we seek to crush expression of personality, or system of belief, or the ability to pursue personal goals and professions – we wrong both the individual and the human species, by undermining individual potential, and so making the species that much less diverse, and therefore, less adaptable. Conversely, when we undermine the flourishing of society by allowing individuals to pursue purely self-interested goals to the detriment of all – short-sighted, self-centered market choices leading to mass pollution and climate change; widespread cell phone use while driving; ideologues who keep their children out of the public schools to indoctrinate them in only one world view – we wrong individuals too. When the individual is allowed by the group to pursue their own myopic interests to the detriment of all, individuals suffer.

Moreover, in all areas of biology it’s essential to understand a species en masse if you want to fully understand an individual organism. Only if you consider a group will you understand which characteristics are necessary for all members of the group to survive and flourish. If you look at an individual being, you see a set of characteristics that could just as well be individual quirks; if you look at the species as a group, you recognize which characteristics all have in common. This is so even when it comes to solitary animals – most cats, for example. We consider each solitary cat as a member of the species cat as well as a particular furry, comfort-loving, furniture-ravaging, mouse-chasing, charmingly mischievous producer-of-the-cutest-offspring-on-earth-namely-kittens animal. If we didn’t perceive them dualistically in this way, we wouldn’t understand much about any one cat, let alone cats as a species. For instance, if we were to encounter an individual animal, but had never encountered or learned about others beforehand, we wouldn’t know what to feed it, how we might need to protect the furniture, or why we should keep a video camera handy when it’s around. And if we need this dualistic perception of cat both as one animal and one of many cats in order to understand it, how much more so for a highly social species such as human beings, whose interests and fates are so intertwined?

The cat example might seem to illustrate such an obvious point as to be unnecessary, but I think we need to remind ourselves of it whenever an ethicist, politician, or anyone else tries to completely separate the interests of the individual from that of the group (or indeed, every time an intellectual tries to divorce fields of inquiry from one another). Generally, great harm comes from the attempt to separate ‘individuals’ and ‘society’ into competing camps, or from acting on the belief that the society doesn’t exist, as Margaret Thatcher once put it.

The Tools of Knowledge by Peter Pullen. Please visit peterpullen.weebly.com

Further Reasons Why Science Needs Philosophy

I agree with Michael Shermer that scientifically verifiable facts about human beings should inform our ethics; to my mind, the best system of ethics is a naturalistic system. Looking outwards at the world provides the raw material for any system of thought. After all, as Aristotle, Hume, and the other empiricist philosophers point out, all knowledge begins with the information we receive through our senses. There is no reason to think that we could think at all if we have never heard, seen, felt, tasted, or smelled anything to think about. However, it’s thinking that allows us to achieve more than just sensing the world would. And philosophy is the human species’ way of taking the art of thinking as far as it can go: in doing philosophy we examine what the information we receive through our senses might mean in a larger context and in a deeper way.

We question, we look for answers restlessly, not only because we want to solve problems, but because we love to do so. Philosophy, after all, translated from the Greek, literally means ‘love of wisdom’. And as we ask and as we look, in the interplay between the input of our senses and the organization of information through our thought, science then affords reality “the opportunity to answer us back”, as Rebecca Newberger Goldstein so beautifully puts it in Plato at the Googleplex: Why Philosophy Won’t Go Away (2014, p.34).

But philosophy not only provides the impetus and the direction for scientific inquiry: once we find out the facts, it helps us figure out what to make of them. At every step of the way, from the application of the rules of logic, to the justification of why we should value or emphasize one set of facts over another in any specific application the formulation of scientific theories relies heavily on philosophy. In fact, science was originally a branch of philosophy – natural philosophy – until that branch of inquiry became so large it specialized and branched off, then branched off again into physics, biology, chemistry, and so forth: we could say that science was grafted out of philosophy.

Those areas of philosophy that didn’t branch off into the sciences or theology remained as the philosophical subspecies of metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and so on, pursued largely behind the walls of academia today. But philosophy is not limited to being an arcane, highly abstract field of inquiry (as fascinating as that can be). Instead, it’s symptomatic of an approach to life for a perceiving, emoting, responding, loving, feeling, suffering, and thinking being, which approach every person partakes in to one level or another. I want to know why, and how, and who, and so on; and not only to know what is, but why I care about it, and why others should too. Philosophy, from its very beginnings, originates in the public square. It is welcoming into one’s self the whole world of things to sense and to imagine with a curious, critical attitude, and engaging in that way of thinking with others. Science forms a big part of this, yet philosophy is prior to, and necessary for, science. To separate philosophy from science is as unhelpful as divorcing the individual from the species: one does not function without the other.

When it comes to understanding the universe, in fact there is no such thing as ‘non-overlapping magisteria’ of thought as Steven Jay Gould put it when he tried (to my mind unsuccessfully) to justify the separation of theology and science, in for example Natural History magazine #106 (1997). Therefore I think it’s a mistake to indulge in the kind of intellectual turf wars that science, philosophy, and other fields of inquiry sometimes have, not only because it sets up mental road blocks to incorporating the full range of evidence and ideas available, but also because it sets a bad example for critical thinking.

A Co-Dependant Relationship

Aristotle, Founding Father of science

Shermer and others do well to remind philosophers – many of whom are sadly remiss in this – that they need science to keep them honest: so that subtle errors in logic and justification, and an over-weddedness to a tradition of thought, can’t lead them too far astray. But ‘philosophy-jeerers’ as Newberger Goldstein calls them, also make a mistake when forgetting how much science owes philosophy, and how heavily the scientists themselves actually depend upon it. For example, although at the beginning of his article Shermer refers to rights theory in philosophy as a popular source of ethics as a contrast to a scientific view, later on in the same piece he refers to ‘natural rights’ – part of rights theory – as a scientific ethical principle! Moreover, like ethics in general, rights theory has always been derived (if indirectly at times) from the application of reason to observed facts about human beings: that we are rational and feeling creatures, that we’re capable of autonomous will, that we seek to live ‘the good life’, and so on. To intimate that rights theory is, or has ever been, a non-empirical view of ethics and an alternative to an empirical view, is to misunderstand what rights theory is and always has been.

Remember also that Aristotle (385-322 BC), philosopher extraordinaire, is one of the earliest and most famous founders of two of the most influential fields of philosophy, ethics and natural philosophy – better known today as science. As so delightfully described in Rebecca Stott’s Darwin’s Ghosts (2012), Aristotle didn’t remain in his armchair (did they have armchairs in ancient Greece?) just spinning abstract theories straight out of his head, arguing points of logic with his fellow philosophers. He looked to the world to provide the raw material with which to craft his theories on the origins and nature of life: diving for specimens of sea flora and fauna, and recording his observations of the behavior of animals and the life-cycles of plants. It was his philosophical mind that drove him to ask the questions and look for answers; and it was nature that provided the subjects of his reasoning.

In the words of Humphrey Bogart, we can see from accounts of Science’s birth “the beginning of a beautiful friendship” between Science and her mother, Philosophy. The most intimate kind of friendship, where the dialogue is open and honest, and each supports the other, guiding one another away from the pitfalls and wrong turns the other doesn’t see. From the very beginning, philosophy has always been there to keep science intellectually honest, supplying the discipline of logic and helping it avoid methodological errors, and how science can be used to help and not harm. Philosophy also makes it clear why there are relatively few direct or easy links from the factual ‘is’ to the ‘ought’ when formulating principles of ethics: it shows science that finding out how things work doesn’t readily indicate how we should apply that information in our lives; and that even the best scientist is prone to bias, misunderstanding, and underestimation of that which we don’t yet know. There is no honest philosophy without science, but there is no science at all without philosophy.

© Amy Cools 2015

Amy Cools’ philosophy degree from Sacramento State University had an emphasis on Applied Ethics and Law. An avid hiker and quilter, she loves traveling, mystery stories, music, coffee, ale, and cheese.