Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Aping Mankind: Neuromania, Darwinitis and the Misrepresentation of Humanity by Raymond Tallis

Daryn Green is of one mind (almost) with Raymond Tallis.

Broadly speaking, Aping Mankind is about sloppy science. That is, it’s an attack on scientism, the mistaken belief that all important questions are best tackled with the use of natural science techniques. It’s about how hubris can cause as prestigious a subject as science to overestimate and overextend itself. More specifically, Aping Mankind is about the impact of this tendency on biological theories of human mental development, with all the philosophical mind/body issues which that involves. Raymond Tallis delivers a heartfelt polemic against what he sees as a great many errors and unproven assumptions, which are wide-ranging and yet interlinked. What holds these assumptions together is a blind adherence to what seems to be the most scientifically-convenient – though not necessarily correct – philosophy, a form of what is called ‘materialism’. In the process Tallis trains his guns on an array of notables, such as John Gray, Daniel Dennett and Susan Blackmore. As ammunition he has coined some new words, for example, those used in the book’s subtitle, ‘neuromania’ and ‘darwinitis’. These describe the current trendy misuse both of neurology and of Darwinism respectively. These seem to me to be justified and apt neologisms, for the ideas, attitudes and movements Professor Tallis has in his sights appear to display elements of dysfunction and ‘contagion’, and to be prey to obsession.

Tallis is not just concerned with the scientific and philosophical issues; he is also deeply concerned about how the oversimplifications, exaggerations and misconceptions he outlines might downgrade what we humans think, both concerning what we are, and what we might become. For the most part, Tallis attacks in order to defend; and the central concept that he is defending is that of the special place of consciousness, and all that flows from this in our behaviour, culture and society. That is to say, he is defending ‘real’ consciousness – the consciousness that since time immemorial people have assumed that they have, not the compromised or illusory ‘consciousness’ left behind once biological determinism (the notion that physical biological mechanisms, not choices, directly and solely govern our behaviour) have robbed consciousness of freedom and agency.

Tallis is apparently well qualified to mount this defence, straddling as he does the sciences and humanities. He was once deeply involved with neurological research, and is now a philosopher [see his regular column in this magazine, ed]. One would be hard pressed to find someone better placed to tackle the issues involved. This is particularly evident in the way he deals with the more technical elements of the book, managing to convey fairly specialised biological information reasonably accessibly to the layperson.

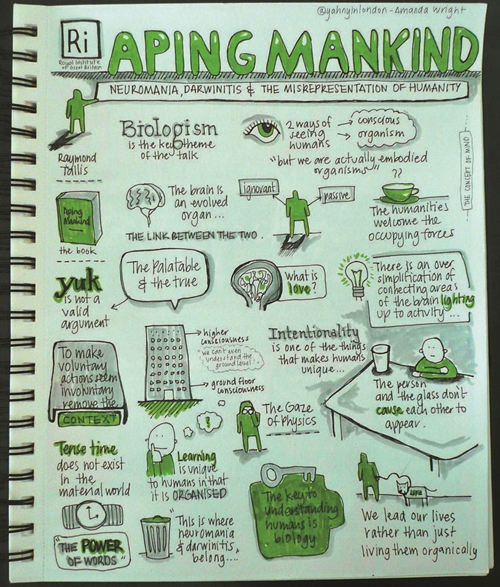

This is a sketchnote by Amanda Wright, who went to a talk by Raymond Tallis at the Royal Institution of Great Britain. To see more of her sketches, visit yahnyinlondon.com. © Amanda Wright

Head Cases

Tallis’s main targets could be placed under four broad headings: neurology, evolutionary theory, the computational theory of mind, and linguistics.

In the case of neurology, he attacks several types of exaggerated claim: for example, those surrounding fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) scans. He points out that these only show relative levels of blood flow or oxygen consumption in different areas of the brain. They do not spell out exactly what the areas of higher activity are doing, nor do they preclude the possibility that the areas of lower consumption are still doing something related and important. Therefore studies which use this technique show much weaker evidence for the localised (or modularised) models of brain function than is usually assumed by the media.

Tallis also strongly challenges the conclusions often drawn from Benjamin Libet’s work. In a series of experiments, Dr Libet sat the participants, electrodes attached to their brains and arms, before a timer adapted to show a revolving dot. He asked them to press a button, and to state the position of the dot on the clock when first aware of their urge to make the movement. By analysing the differences in timings between conscious urge and unconscious signals, it was discovered that the brain prepared to make the hand movement before there was any awareness of the decision to move. This is often interpreted as evidence that our brains, and not our minds, are in charge of making our decisions. But as Tallis points out, the experiment does not in any way cover the issue of free will in the wider circumstances – for example, in the decision of the subject to take part in the experiment; the decision to book a particular day and time to be tested, and so forth. Also, the usual conclusions from the experiment do not explain how we can override our inner promptings when we choose to do so.

Above all Tallis calls attention to the often assumed, and yet unproven, notion of identity between the mind and the brain – tracing the tendency to equate them all the way back to the ancient Greeks about 2,500 years ago. He presents a number of obstacles in the Identity Theory’s path: for instance, the counter-causal (and thus counter-material?) direction of the intentional gaze – our looking at objects goes against the causal direction taken by the objects’ physically causing changes in our eyes and brains; or the problem of how, on encountering an object, the sensory data gathered is experienced both as a unity and as a multiplicity – ‘merged’ and yet not ‘mushed’. He poses this problem as it affects ever-higher levels of consciousness. But most importantly, Tallis calls attention to the sheer mystery of how you can get from the physical firings of synapses – or the whizzings of electrons in computer chips for that matter – to anything like self-awareness, without the ‘sleight of hand’ of positing a small organising consciousness (or ‘homunculus’), which organising consciousness is the very thing we wish to explain.

Escaping Evolution

Tallis is also strongly against the unqualified use of evolutionary theory to account for our nature. He believes the abilities of our species to outgrow unconscious nature, and thus compromise its absolute rule, are very well developed. (He sees the hand as an important initial driver in this regard. He also calls attention to the way we narrate our lives within a ‘community of minds’.) Things can be consciously explicit to us in a way, or to a degree, that they simply aren’t to other animals. Thus Tallis also opposes the prevalent tendency to animalise humans and anthropomorphise animals, arguing that the evidence suggests a huge gulf even between us and apes. He is also very critical of that recent evolutionary offshoot, ‘meme theory’ – the idea that within consciousness, cultural objects can replicate in a manner strongly analogous to genes – pointing out that such ‘objects’ don’t have the unitary nature necessary for the analogy to work.

While tackling the ‘computational theory’ of mind, Tallis highlights the fact that in the domain of ‘artificial intelligence’ (so-called) no one has come close to producing a conscious machine. Not only is there no significant evidence of structural similarities between brains and computers, even if there were, this wouldn’t constitute a telling advance in explaining consciousness. Moreover, when it comes to talking about the mind, says Tallis, the sloppy use of words or their natural ambiguity feeds unjustified assumptions. For example, the word ‘information’ is often used in a way which conflates its specialist engineering sense with its ordinary sense – an illegitimate move which lends itself particularly to justifying the computational theory of mind.

Tallis & Lewis (C.S.)

This book clearly fits into the broad traditions of philosophical and popular scientific writing, but as I searched my bookshelves and my memory, a more revealing connection came to mind. Interesting parallels can be drawn between this book and a very short volume by C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (1943).

On the surface the two authors seem the oddest of bedfellows – Lewis is a committed Christian, Tallis a committed atheist. Their foes have differences too – Lewis’s initial salvoes are directed towards a couple of relativist grammarians! But in both books the authors show themselves to be highly sophisticated thinkers who feel they have caught at least a glimpse of the true richness and complexity of the human condition – and consequently are intent on defending this healthy position of abundance against the insidious creep of reductionism. And Lewis too sees scientism as a key source of the problem, wishing that science, “When it explained… would not explain away.” Tallis makes almost the same remark as a response to Daniel Dennett. Like many philosophers, Dennett commits the error of reducing consciousness to nothing, not just by way of de-emphasis, but in the literal sense of trying to deny its existence altogether.

Both writers show a degree of belligerence; but certainly part of the pugnacity of Tallis’s defence stems from the fact that he feels (I think with some justification) that many of his comrades in the humanities have capitulated rather tamely to biology’s encroachment – or even collaborated – rather than standing firm against the inappropriately-qualified invader.

Too Anti-Materialist

This book is a welcome corrective to what Tallis calls the ‘BOLD rush’ of biologism, (‘BOLD’ standing for ‘Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent’). But there are a few slight criticisms that I would make.

First, several parts of the book are adapted from previously published material. While this may have added to the book’s breadth and depth, perhaps it’s also why there’s a certain amount of near-repetition in the writing (the problem eases in the second half). This should not deter the interested reader, but nonetheless it is a shame, for it means the quality of the narrative line does not match the quality either of the content, or of Tallis’s prose.

Second, I think Tallis makes some questionable assertions. At one point he claims that consciousness does not confer an evolutionary advantage. But surely there are some beneficial skills which are consciousness-dependent. In particular one thinks of the social leverage which our fuller awareness of self and others brings. He also claims that a conscious observer is required in order to give matter a temporal reference point (ie, to locate it in time). This smacks of an idealism which elsewhere in his argument he seems to deny. (Idealism is the view that the material world does not exist independently of mind.) At other places he seems to use the properties of the contents of mind as evidence against mind/brain identity in ways that seem simply question-begging. For example, the aforementioned counter-causal direction of the intentional gaze (again, we gaze at objects, not from objects). Surely this is unproblematic once the usual conception of consciousness is accepted, as being about things; and so one is simply thrown back upon the central philosophical problem.

This feeds into my last, and most substantive criticism: that although Tallis rightly challenges the assumptions of many materialists/identity theorist, I feel that he over-eggs the pudding. For although he undoubtedly delivers many a blow to materialism, sending it reeling back on its heels, for me he does not deliver a knock-out punch; rather, he builds up a case. But this is a crucial distinction. For an atheist non-dualist like Tallis or this reviewer (‘dualism’ being the notion that reality consists of two basic substances, mind and matter), without a cast iron disproof of materialism, surely this suggests that it remains, not just a card on the table, but still arguably the strongest card. After all, a distinction must be drawn between the sort of crass materialism that I think Tallis successfully – and wittily – debunks, and a potentially much more sophisticated idea of mind-brain identity, perhaps centuries beyond our understanding, and perhaps of such a nature that it would be impossible for us to fully understand it. In seeming to reject this latter notion too, Tallis is surely a lot closer to dualism than he admits, although in the end – via dismissing panpsychism (all matter has a mental aspect) and quantum theory as explanations of consciousness – he describes himself as an ‘ontological agnostic’, (i.e., a ‘don’t know’ with respect to what we ultimately are). After reading this important and thought-provoking book, this was also where I found myself.

© Daryn Green 2012

Daryn Green is a carer, and also works as a supply teacher in North London.

• Aping Mankind: Neuromania, Darwinitis and the Misrepresentation of Humanity by Raymond Tallis, Acumen, 400pps, £25, ISBN 978-1844652723.