Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Dancing with Absurdity

Fred Leavitt argues that our most cherished beliefs are probably wrong.

Imagine that you’ve developed a new lie detector test and recruit a thousand people to try to beat it. You give them a series of questions and ask them to tell one or more lies among their answers. Your device detects every lie and never calls an honest response a lie.

Then comes subject 1001. Asked a question, he answers “yes” and your device indicates that he’s telling the truth. But you ask virtually the same question immediately afterwards, he says “no,” and the device again registers truthfulness. The man swears that he believes what he said. He submits to a psychiatric evaluation and is found free of any major disorder. He is not delusional. How is this possible?

Here are the two questions:

1. Do you anticipate with near certainty the occurrence of thousands of events: the sun will rise, the alarm will ring, the car will start, food will have a certain taste, and friends and enemies will behave in broadly predictable ways?

2. Do you believe you can know that the sun will rise, the alarm will ring, the car will start, food will have a certain taste, how friends and enemies will behave; or indeed, know anything with more than the slightest probability of being correct?

Albert Camus wrote that human beings try to convince themselves that their existence is not absurd [see Brief Lives in this issue – Ed]. What could be more absurd than to be certain of two important beliefs that contradict each other?

I am subject 1001, and my contradictory beliefs make me lonely. I long for company. That’s my motivation for writing this. Read it and you too will dance with absurdity.

Radical Skepticism

Plato wrote that we’re like prisoners in a cave with our backs to a fire which casts shadows on the wall in front of us, and the shadows are all we can know. Other major philosophers have concluded that we can know nothing with certainty – or even with probability. Many have tried to refute this position, called radical skepticism. They have failed. Of course they did: radical skepticism is the correct worldview.

Even most cynics believe some things more than others: they trust analytic chemistry more than weather forecasting. They know that the outcome of a single toss of a fair coin is uncertain, but would gladly bet against heads turning up one hundred times in a row, and be sure of chicanery if it did. Radical skeptics sneer at these cynics for being too trusting. They see no difference between analytic chemistry and ouija boards. They deny the possibility of any knowledge – except for the indisputable conclusion that we can’t know anything. They contend that a coin is no more likely to turn up heads than become a Rembrandt painting or Tucson, Arizona. Camus opened his Myth of Sisyphus (1942) with the sentence, “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide.” Radical skeptics reserve judgment about the certainty of death, or that someone named Camus ever existed.

The burden of proof lies with whoever claims knowledge. Nobody has disproved the existence of ghosts, but that’s not evidence for their existence. Similarly, even if arguments for radical skepticism were deficient (and they’re not), knowledge claims would be unjustified without adequate evidence. An infinite number of alternatives always exist to even the most persuasive inferences from any evidence. The butler did not always do it, even when all the evidence points in his direction.

The Four Pillars

Four separate pillars (seemingly) support our understanding of the world. That is, everything we think we know comes from one of four sources. Immanuel Kant proposed one source. He argued that we are born with certain innate knowledge. Religious revelation is a second pillar. People of faith are told who created the world, when He did it (almost always by a He, and in some religions, to the day), and what will happen when we die. Reason is a third pillar. Humans discern patterns, and use mathematics and logic to make deductions. The fourth pillar is sensory data. We interact with the world through the five senses, and then we combine this with logic to advance from simple observations to complex inferences. The naïve view is that we observe, and then we know. Seeing is believing. Ha!

Innate Knowledge

Kant claimed that certain key beliefs, such as ‘Every event has a cause’, precede all experience, because they are preconditions for human thinking. Experiments have shown that even six-month old babies act as though they understand connections between causes and effects. In Don Marquis’s Tales of Archy and Mehitabel, Archy the cockroach pities humans because they are born ignorant and must struggle to learn the ways of the world. Archy says that insects are born knowing all they need to know. Archy would have approved of Kant.

But radical skeptics question the correctness of beliefs, not their origins. Newly hatched ducklings ‘know’ that the first moving object they see will be their mother, so they follow it. But when nasty biologists substitute objects like shiny balls or shoes, the ducklings follow those too. Their ‘knowledge’ is incorrect.

Religious Revelation

Imagine a science fiction scenario in which extraterrestrial beings assemble the leaders of today’s more than 730 world religions. Eager to know which is correct, they give each leader two days to make his or her case. What evidence might the leaders give? Typical arguments might include, “God told me this” or “On Easter Sunday I bought a bushel of potatoes, and one of them was the spitting image of the Virgin Mary.” Would a Christian’s argument that the Son of God rose from the dead play better to the aliens than the Hindu idea that each soul undergoes many reincarnations until united with the universal soul? Maybe the major religions would expect their large numbers of devotees to count in their favor; but large numbers of believers do not constitute proof of a belief. Furthermore, no religion attracts a majority of the world’s people. ET would end up shaking her three heads in dismay.

Moreover, if religious beliefs were culturally independent, religious preferences would be independent of time and place of upbringing. They are, of course, not. More Baptists live in Biloxi than Bombay, more Jews in Jerusalem than Jakarta, and more Muslims in Malaysia than Mississipi. This reflects the obvious fact that people living within a broad general region are exposed to the same influences, and are therefore influenced to have the same beliefs.

Reasoning

Many philosophers believe that the only path to certain knowledge is through reason. But reasoning abilities are greatly overrated (which presents us with a paradox, since this article attempts to persuade through reasoning). The skeptic philosopher Agrippa (1st C AD) contended that all arguments claiming to establish anything with certainty must commit at least one of three fallacies:

1. Infinite regress. The claim that a statement is true needs evidence to support it. But the evidence must also be supported, and that evidence too, and on and on, ad infinitum.

2. Uncertain assumptions. Foundationalists claim that some beliefs are self-evident, so can be used as starting points for complex arguments. For some foundationalists, mathematics and logic provide such basic beliefs: ‘2+2=4’; ‘If X is true, then X cannot be false’. Other foundationalists insist that basic beliefs come from direct sensory experience: ‘That cat is black’. Internal feeling is another candidate: a person who claims to have a headache may be lying, but it is hard to see how he or she could be mistaken. Nevertheless, none of these basic belief candidates lead to the enormous number of complex, detailed beliefs that are part of everyone’s worldview.

3. Circularity. The argument involves a vicious circle. Coherentists assert that statements can be considered provisionally true if they fit into a coherent system of beliefs. But coherentism is circular: A explains B, B explains C, and C explains A. Circular arguments are invalid. Furthermore, statements may cohere with many others, some of which are false. So it is possible to develop a belief system that is both coherent and entirely untrue.

If reason were so powerful, people would more often be persuaded to change their views. Yet throughout history, illustrious philosophers wrote lengthy, reasonable arguments, and illustrious others rebutted them. Similarily, every year, brilliant lawyers present arguments to the U.S. Supreme Court. Every year the nine Justices, chosen in large part because of their exceptional powers of reasoning, listen attentively. But whenever the dust has settled on arguments concerning gun control, abortion, affirmative action and so forth, the votes of most judges have been highly predictable. Brilliant Antonin Scalia drew one conclusion, brilliant Ruth Bader Ginsburg the opposite. And brilliant Clarence Thomas was mute. “So convenient a thing is it to be a rational creature, since it enables us to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to” – Ben Franklin.

Jean Piaget showed that young children invariably think illogically in some situations. How can we be so arrogant as to assume that Twenty-First Century adult Homo sapiens has reached the pinnacle of logical thinking!

A lot of everyday reasoning (and most science) is inductive. This means that our senses reveal the immediate present, and we use reason to generalize about the unobserved world from what we immediately see. But the generalizations require the assumption that what has not been observed is similar to what has been observed, or that the future will resemble the past. And as David Hume noted, we cannot justify that assumption from experience. To show this, Bertrand Russell invoked a chicken, fed by a man every day of its life and eventually learning to expect its daily feedings, but in the end having its neck wrung by the same man. Russell added that although we believe that the sun will rise tomorrow, we are in no better position to judge than about tomorrow than was the chicken. Russell concluded that there is no rational basis for induction.

Following are two examples of inductive reasoning in mathematics. The first leads to a true conclusion, the next to a false one.

1. Consider the numbers 5, 15, 35, 45, 65, 95. Every number ends in 5 and is divisible by 5. An inductive inference is that every number that ends in 5 is divisible by 5. This inference is correct.

2. Consider the numbers 7, 17, 37, 47, 67, 97. Every number ends in 7 and is a prime. An inductive inference is that every number that ends in 7 is a prime. The inference is false. For example, 27 is divisible by 3 and 9.

Here is a nonmathematical example in which an inductive inference may be incorrect: He is 50. He is articulate and healthy-looking. He drives a nice car. Therefore, at some point in his life he probably worked for a living. However, it’s quite possible that somewhere on earth lives a bright middle-aged Kuwaiti emir, or Rockefeller, or Bush, with hands never soiled by work, who drives a different luxury car every day.

Hume destroyed the illusion that induction can be rationally justified, and Nelson Goodman put a stake through its dead heart. Goodman showed that a limitless diversity of inductive inferences can be drawn from any body of data. For example, since all emeralds ever observed have been green, the obvious inductive inference is that all emeralds are green. So Goodman coined a new word, ‘grue’, which refers to objects that are green before a certain date in the future and blue from that date on. Prior to that future date, all evidence supporting the induction ‘All emeralds are green’ equally supports ‘All emeralds are grue’. And using similar definitions, ‘All emeralds are grack, grellow, or gravender’.

So inductive reasoning is imperfect. But deductive reasoning, which does not depend on evidence from the world, follows universal principles based on rules of logic, probability theory, and decision theory. Conclusions from such reasoning must be correct – with iron-clad certainty. Or maybe not. William Alston observed that “anything that would count as showing that deduction is reliable would have to involve deductive inference and so would assume the reliability of deduction” (The Reliability of Sense Perception, 1993). Complicating matters even further, logicians have proposed many principles of reasoning, several of which are incompatible with each other.

Moreover, even if two disputants each reason flawlessly, they might never come to agreement if they start from different premises. And premises come from observations, which, as shown below, are unreliable. Consider a syllogism: All A is B. Some C is not B. Therefore, some C is not A. Whether or not you judge the reasoning valid, unless you know from observation what A, B, and C represent, you have not increased your knowledge of the world. As Albert Einstein said, “All knowledge of reality starts from experience and ends in it. Propositions arrived at by purely logical means are completely empty as regards reality” (Ideas and Opinions, 1954).

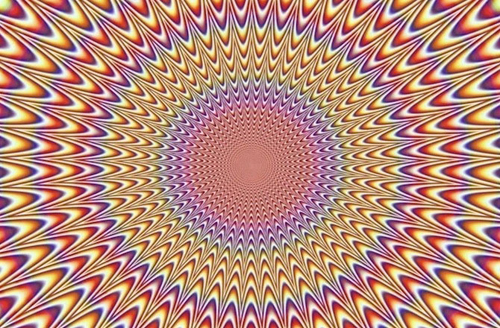

“Yet reliable estimation of the frequency of illusions and hallucinations is impossible.”

Sensory Data

Empiricists believe that everything we know comes through observations and inferences induced from them. Maybe, but almost all important observations are second- or third- or tenth- hand. Few people have walked on the moon or seen the chromosomes of a fruit fly, and nobody I know attended the signing of the Magna Carta. Furthermore, observations don’t help distinguish truth from illusion. Mental institutions are crammed with people who hear voices, or speak with long-dead relatives. And just because people outside institutions are in the majority does not necessarily make their visions more credible.

Empiricists don’t insist that we see the world with total accuracy. They acknowledge the occurrence of hallucinations and sensory illusions; but they say that hallucinations are rare, and that illusions play a trivial role in daily life. They conclude that sensory data are generally accurate. Moreover, empiricists Gilbert Ryle and John Austin argued that our ability to detect illusions is evidence for the general trustworthiness of our senses. That is, from the fact that imperfections are infrequently detected, they made the dubious inferences that imperfections are rare and perceptions are typically accurate. Yet reliable estimation of the frequency of illusions and hallucinations is impossible. You may be experiencing one this very moment and not know it. Furthermore, even if our sensory systems were perfect, we’d still face two insurmountable obstacles to certainty. First, the fidelity of human memory is, to put it charitably, considerably less than high. Second, an infinite number of interpretations are compatible with any given perception. Maybe it’s churlish to point out yet another problem, but, strictly speaking, empiricism is self-refuting – the claim that all knowledge is gained through the senses is a claim not gained through the senses.

We can never be certain or even mildly confident of the feelings or intentions of others. Polygraph expert Leonard Saxe said, “We couldn’t get through the day without being deceptive.” Daniel Ariely and colleagues analyzed several data sets – from insurance claims to employment histories to the treatment records of doctors and dentists. They concluded that almost everybody lies. Self-deception is also very common. Any form of information about anything may be incorrect because of unintentional error, misguided theory, or deliberate deception. Our world of used-car salesmen, pyramid schemes and politicians gives good reason for generalized suspicion. We are constantly fed inaccurate and misleading information. My book Dancing With Absurdity gives dozens of examples from personal, historic, journalistic, governmental, corporate, and scientific sources. Furthermore, we may be manipulated in subtle ways. The protozoan Toxoplasma gondii causes a disease called toxoplasmosis that alters their hosts’ behaviors. Infected married women are more likely than noninfected to have affairs, and infected men tend to be more aggressive. Schizophrenics are more likely than non-schizophrenics to have toxoplasmosis. Some researchers estimate that Toxoplasma gondii has infected more than 30% of all humans. Toxoplasma gondii is one parasite. Undiscovered others may also affect human behavior.

Nor do observations tell us about any underlying reality. Friedrich Nietzsche wrote that we can get no closer to reality than our own sense experience, and have no way of evaluating its correspondence with the real world. Immanuel Kant distinguished between noumena and phenomena. He called external reality the noumena. But we perceive only phenomena – the appearances – since all our knowledge is filtered through our mental faculties.

Science

Reasoning and sensory data come together in the leading modern contender for establishing certain knowledge: science. Our ancestors lived in a world of unpredictable famines, floods, plagues, and saber-toothed tigers. To explain such events, the more imaginative among them constructed rich cosmologies of gods, demons and other supernatural forces. A few individuals noticed that some phenomena occur in recurring patterns. These primitive scientists measured, experimented, and theorized. Their intellectual descendants made science the preferred method for advancing knowledge. The scientific method is the most powerful method ever developed for studying the properties of the world. Science is empiricism in its most sophisticated form. Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Freud, and others may have probed deeper into the human condition; but science has dramatically changed how people live. Yet there are reasons to be wary about scientific studies. Errors are common, and there have been cases of scientific fraud, perpetrated by both mediocre and eminent scientists. More importantly, science is always a work in progress, its conclusions open to later challenge and revision, rather than being claims of certainty.

In fact, many philosophers claim that the scientific approach is thoroughly flawed. Consider two syllogisms:

1. Theory T predicts that, under carefully specified conditions, outcome O will occur. I arrange for these conditions, and O occurs. Therefore, I have proven theory T.

2. Theory T predicts that, under carefully specified conditions, outcome O will occur. I arrange for the conditions, but fail to obtain the predicted outcome. Therefore, I have disproven T.

The second syllogism is valid. If the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true. The first syllogism is invalid. Counterexamples are easy to imagine. For example, a prediction O from the hypothesis T that ‘Unicorns run around at night in Golden Gate Park’ is that animal droppings will be found in the park in the morning. But finding animal droppings in the morning would prove nothing about unicorns. Yet this invalid syllogism form is the basis of much scientific reasoning; and of much of everyday reasoning too.

Probability

Without some certainty to rest on, probability cannot be meaningfully assessed. But we assess probability by using ideas that themselves only have a probability relative to further ideas. For instance, in calculating the probability of getting two sixes on a roll of dice, some of the many things that are assumed are that (a) the dice are fair; (b) the roll is fair; (c) the numbers that come up on the two dice are independent of each other; (d) the probability of two independent events occurring simultaneously is the product of their independent probabilities. If any of the assumptions are wrong, so is the final probability. What is the probability that your next door neighbor or close friend – who you’ve had over for dinner, who has baby-sat your children, who was maid of honor/best man at your wedding – is a serial killer? Al Qaeda terrorist? Participant in a witness protection program? Of the other gender from what you believe? CIA spy? Polygamist? Embezzler?

You may say “Zero”, but people just like you have been stunned to find out otherwise. The best spies do not look like Sean Connery in his prime, bench press five hundred pounds, and drink double martinis, shaken, not stirred.

Conclusions

The skeptical argument can be put even more strongly: everything we think we know is probably false, since the assumptions upon which our beliefs are based are selected from an infinite pool of alternatives.

The nearest star to our sun is about twenty-four trillion miles away. Our Milky Way galaxy has hundreds of billions of stars, some of them thousands of times larger than the sun. A computer simulation estimated five hundred billion galaxies. The prestigious scientific journal Nature published a study suggesting that there are about three hundred sextillion (3 x 1023) stars in the universe. The speed of light is a little over 186,000 miles per second, so light can travel from the Earth to the Moon in about 1.3 seconds. Yet a beam of light would take about twenty-seven billion years to travel from one end to the other of the known universe (and that’s not factoring in universal expansion). Some people may conceive of a universe infinite in size and duration, or with equal ease imagine a universe with boundaries. Both strike me as wildly improbable, yet I can’t even conceive of a third alternative. With that in mind, the leap from our infinitesimally tiny part of the universe to claims about eternal and universal laws seems preposterous. How can anyone consider these numbers and continue to believe that earthlings have discovered universal laws?

So, this article leaves readers with three possibilities, and the last two require a profound overhaul of worldview. Acceptance of either would leave no guidelines for behaving one way rather than another, as the world would then be completely unpredictable. I grant the implication. This article is an attempt to encourage others to help figure out what to do.

Possibility 1. My reasoning is flawed. One or more errors invalidate the conclusions.

Philosopher G.E. Moore argued against radical skepticism. He wrote that, if a seemingly sound argument leads to an implausible conclusion, the argument may not be sound after all. There is probably an error in either the premises or the argument form. So readers should evaluate every step leading to my outrageous conclusions. My PhD is not in philosophy, and my knowledge of the literature is limited, so there may be some important omissions. But I’m convinced that there are no serious errors of reasoning.

Possibility 2. Radical skepticism is correct. We cannot know anything, apart from the fact that radical skepticism is correct.

Possibility 3. We must give up on reasoning as a path to the truth.

© Dr Fred Leavitt 2015

Fred Leavitt received his PhD from the University of Michigan and taught for many years at Cal State University. He’s written books on drugs, research methodology in psychology and medicine, philosophy, and medical practices, and a novel.