Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Bad Arguments That Make You Smarter

Henrik Schoeneberg gets smart about fallacious reasoning.

Have you ever heard of the Straw Man fallacy, or the Red Herring fallacy? If not, perhaps you will be interested to know that these form parts of a set of concepts that have the potential to enhance your thinking power. In fact, by the time you finish reading this article you will have become smarter, because you will see the flaws in your own and others’ arguments more clearly.

Think of your brain as a toolbox. In the same way that there are tools for building, there are what philosopher Daniel Dennett calls ‘thinking tools’. Language, for instance, is a thinking tool, because it enables us to think better, through internal dialogue and by the sharing of ideas with others. Whenever a useful new word is invented, a new thinking tool is made available.

It didn’t used to be thought that we require tools for thinking better. Classical economic theory, for instance, is based on the assumption that we tend to make rational decisions. However, in the last hundred years, cognitive science has made it increasingly evident that we largely see the world through biases, and do not reliably think either rationally or objectively when left to our own devices, including in our economic choices. To counteract these psychological tendencies, we need to make better use of the thinking tools that have been developed since Aristotle’s invention of logic.

A particular step forward has been the identification and labelling of various different types of bad argument, collectively known as informal fallacies. These now go by widely-recognized and sometimes colourful names. For instance, an ad hominem (Latin for ‘to the man’) is a type of fallacy where you counteract the force of someone’s argument by attacking their character instead of their argument. This is a bad way of arguing because what is usually important is not the messenger but the message. Nonetheless, ad hominem arguments are widely used in all kinds of situations – for instance in political campaigns, where disproportionate, irrelevant or downright dishonest personal attacks are often used to overshadow an opponent’s actual arguments.

Many fallacious arguments might seem trivial at first glance. Of course it is not right to assume that one rude tourist represents an entire nation’s attitude; shouldn’t we know that? Weshould, but we often don’t: in practice people often fall victim to the hasty generalization fallacy. Or how many of us have not committed the argument from emotion fallacy; for instance, when we unjustly blame each other because we’re upset? It would have been better if we had calmed ourselves down before trying to talk things through. But in fact, it is just because we are so prone to irrational thinking that it is very useful to be acquainted with even the most apparently trivial types of fallacies. This way we’re reminded of our own irrational shortcomings and we can better keep them in check. As they say at addiction clinics, the first step toward being cured is to acknowledge that you have a problem. Furthermore we become better at analyzing the arguments of others when we know about what types of bad arguments there are. Categorizing and naming bad arguments helps to systematize our thoughts so that we can quickly point out what exactly is wrong with an argument. So when we are acquainted with fallacies we become more persuasive debaters. Another handy attribute of fallacies is that in talking about them we can use terminology that has the authority of logic! It may carry more weight if I tell you that you’re using an ad hominem argument against me, than if I simply say that I think it’s a bad way of arguing to attack my character instead of my argument. So when we call someone out for using an ad hominem argument, they might think, “If what she is pointing out to me has a technical name – ad hominem – perhaps she really is onto something?”

More Biases & Fallacies

The concept of fallacies is closely tied to the concept of biases. Some biases even have the word ‘fallacy’ in their names, such as the gambler’s fallacy.

A bias is a prejudice or a preconceived notion. Biases are upheld either through pure ignorance or through fallacies. It is a distorted interpretation of facts, and you need bad arguments to support such views. So you can reduce your biases by becoming more acquainted with fallacies and their illegitimate claims to reason.

One of the most prevalent types of biases is the confirmation bias. This is our tendency to seek out or notice information that supports our pre-existing ideas, rather than to look for unbiased information that draw us nearer to the truth. You can see the confirmation bias operating in claims like this: “I’ve read the health warnings, but my uncle smokes and he’s fine, so smoking can’t be so bad.” In this case, the fallacy of generalising from limited anecdotal evidence is used to counter the widely-established scientific finding that smoking can kill you.

A Dream of Reason

Just being acquainted with some of the tools of reason can change our frame of mind and make us more prone to think rationally. This is why philosopher Ken Taylor’s twist on Plato’s ideal state ruled by philosopher kings isn’t so far fetched. Plato was right, he says; people generally are ruled by appetite and passion rather than reason, so philosophers trained in the use of reason should rule. But not just an elite few of them; instead we should strive to make philosopher kings – clear rational deep thinkers – out of everyone.

This was also the dream of Bertrand Russell. He too wanted to make us all better critical thinkers. When asked in a 1959 BBC television interview what advice he would give to future generations, Russell responded in a way that rather nicely pins down what any discussion of biases and fallacies amounts to: “When you are studying any matter or considering a philosophy, ask yourself only what are the facts and what is the truth that the facts bear out. Never let yourself be diverted either by what you wish to believe or by what you think would have beneficent social effects if it were believed, but look only and surely at what are the facts.”

Straw Men Eat Red Herrings

In light of this advice, let’s look at the concepts I mentioned at the start.

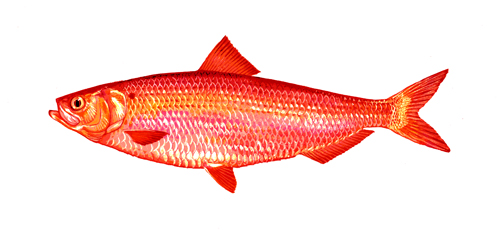

The Straw Man is a fallacy where someone attacks a weaker version of someone’s argument, or perhaps a weaker, different argument for the same point – just as when soldiers train with bayonets by attacking a straw man rather than the real enemy. The Red Herring fallacy is a kind of distraction whereby someone wishing to oppose some conclusion produces and tears down not just a weaker distorted version of the original argument, but an entirely unrelated argument. The fallacy takes its name from when a piece of smoked herring is thrown at fox hounds to lead them in another direction. In the following example, Sandy’s response to Peter is a red herring:

Peter: “I don’t think we should build a new homeless shelter right now. We need more money to maintain the power grid.”

Sandy: “How can you not care about the homeless? That’s just heartless.”

Sandy attacks a different argument than Peter’s own point. Peter didn’t say he didn’t care about the homeless; he might be volunteering at a soup kitchen for all Sandy knows. It just so happens that he thinks that energy supply is also important, and that priorities have to be chosen. A red herring argument also presents itself if someone says that it is wrong to be concerned with animal welfare when there is so much human suffering going on. The concern for animals is not related to the point concerning human suffering, and bringing an unrelated argument into a debate in order to justify your position is a red herring. But in the case of both fallacies, as Russell says, you have to make sure that you “look only at what are the facts and what is the truth that the facts bear out.” Otherwise you risk jumping to hasty conclusions and falling into argumentative traps.

Actively striving to follow the truth above all else and not taking for granted that we do is necessary for critical thinking, and this can be encouraged by getting acquainted with various types of fallacies. It might surprise you how many straw men, red herrings, ad hominem attacks, hasty generalizations, and arguments from emotion, you can find all around you; and how much smarter it makes you just to have knowledge of these fallacies.

© Henrik Schoeneberg 2016

Henrik Schoeneberg has a masters degree in philosophy of science. In his home country of Denmark he is also the highest authority in the field of Veterinary Communication – a subject he introduced to the Danish veterinary profession. Teaching communication is one reason why he has an interest in the subject of fallacies.

Some Other Informal Fallacies

• No True Scotsman: (“No Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge” “No? But my Uncle Hamish does!” “Oh… well, no true Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge.”)

• Begging the Question (petitio principii): A type of circular reasoning where the conclusion supposedly to be proved is smuggled into the premises of the argument.

• Appeal to Authority: An illegitimate attempt to win argument by irrelevant claim of expertise

• Appeal to the Stone (Argumentum ad lapidum): The fallacy of dismissing a claim as obviously absurd without providing proof of its absurdity.

Informal fallacies should not be confused with formal fallacies, which always involve a flaw in the logical structure of an inductive or deductive argument. One example of a formal fallacy is Affirming the Consequent. “If A is true, then B is true. B is true. Therefore A is true.” (This argument is flawed because B might be true even if A is not true).