Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Television

Breaking Bad

Psychologist Joe MacDonagh and philosopher Sheridan Hough each watch what happens when society breaks.

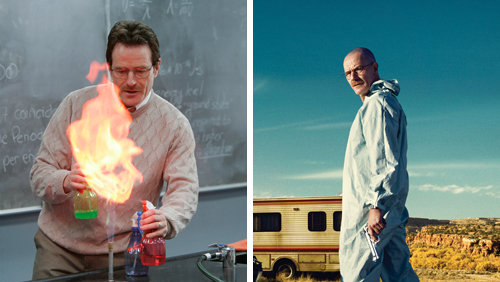

The television series Breaking Bad has been critically and popularly successful on both sides of the Atlantic. It is the story of a chemistry teacher, Walter White, who contracts lung cancer and then decides to start ‘cooking’ crystal meth (methamphetamine) to earn money to support his family after he is dead. There are many plot spoilers ahead so don’t read further if you don’t want to know what happens at the end.

Though spread over six series, some critics have said that this new generation television series is actually one big film, a type of roman-fleuve for television screens. Though, to cut right to the end, his family life is destroyed, his family home is taken over by the Drug Enforcement Authority and he has lost most of the money he earned through manufacturing illicit drugs Walter has actually realised his existential potential through doing something he said made him feel ‘alive’. This was at the expense of almost everyone around him who he loved and cared for.

Chemistry teacher one day, crystal meth cook the next

All Breaking Bad photos © AMC 2008-2013

The beauty of the story is that we very slowly see him sinking into amorality and a moral abyss. He starts by producing crystal meth in the basement of the home of his former student, Jesse, but soon he is cooking professionally for a drugs syndicate with connections to Mexican crime figures, which is then taken over by a group of neo-Nazis. Gradually he goes from someone who has a set target of how much he wants to earn to provide for his family, to someone who enjoys the power that allows him to have people killed because they could incriminate him.

There are shades of Shakespearean tragedy in the series; a once-great chemistry teacher who at college started what was to be an internationally successful science company is reduced to dealing with criminals and criminal lawyers who have no sense of the consequences of their actions for others and will kill anyone who stands in their way, even children. It is only when Walter has literally lost it all, except his own life in which his cancer has re-emerged, that he sees what he has done for the sake of feeling empowered. Macbeth is probably closest in tragic terms as Walter also has a strong willed wife, Skyler, and realises at the end that, as Macbeth says in Act 3:

“I am in blood

Stepp’d in so far that, should I wade no more,

Returning were as tedious as go o’er.”

Existentialists would be proud, possibly, of Walter during his early drug career, as he acts in good faith; he answers what he believes is called upon in his nature, what for him it truly is to be. Instead of being a downtrodden teacher reduced to washing cars to supplement his household income (when he could have been involved in his start-up from college had he been brave enough), he transforms himself into someone who is so needed by criminals that he is able to look them in the eye and say “remember my name,” a phrase which has inspired countless tee shirts bearing a picture of Walter as Heisenberg, his criminal pseudonym. At another stage he brags to Skyler that instead of being at the mercy of a crime overlord “I’m the one who does the knocking.” Subsequent events show that Walter isn’t as much in charge of events as he thinks. He is naïve and deluded in equal measure until his insight at the end but is tolerated as long as he is of use to the crime syndicates.

The true moral heroes of Breaking Bad are Walter’s brother-in-law Hank, a DEA agent, and Jesse, the former student with whom he cooks the crystal meth. Hank is a wisecracking but very substantial and reflective figure who has to cope with being shot because of being mistaken for Walter by Mexican gunmen and who pieces the whole mystery together before being the victim of Walter’s naivety and lack of insight.

The true moral insight comes from Jesse, who goes from being a fairly ignorant, dope-smoking school drop-out who cooks small quantities of crystal meth to someone who questions the morality of what he is doing and the purpose of his life. Through the death of two loved ones he sees what Walter does not, that it is his own actions that are destroying those around him, strangers and loved ones alike. For example, at a drugs recovery group he points out that if we are to accept who we are that may mean not accepting the profound hurt we cause others. Self acceptance may actually mean not accepting responsibility or guilt and not really feeling contrite, which Walter never seems to do until the very end.

Breaking Bad is a tale for our times. Its seeming amorality and lionising of those committing criminal acts would not have been tolerated before now. It is, nonetheless, a profoundly moral story which answers the question of what it would be like to make substantial amounts of money from drugs, if one wasn’t a career criminal but just someone who produced them and who could go home each evening.

Besides a captivating, unputdownable quality it is also uses stylish film techniques such as flash forwards and flashbacks and humorous as well as poignant framing and writing. It is an excellent series, many episodes of which have a place in discussions in philosophy classes, prompting as it does questions such as “what is it to be good or bad?”, “what are the consequences of our actions?” and “is life merely about getting what we can from whom we can while we can?” or is life, as Macbeth says, “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”? Watch Breaking Bad and find out!

© Dr J. MacDonagh 2016

Joe MacDonagh is a psychologist, and lectures at Institute of Technology Tallaght in Dublin.

The action of Breaking Bad is a meticulously crafted narrative arc, one that stretches over five years, 62 episodes, and roughly 46 and a half hours of viewing time. Of course, series creator Vince Gilligan and his writing team faced the usual storytelling challenges: choices must be plausible, with cause and effect firmly in place. The unforeseen and untoward must be accommodated by some sense of how the world actually operates: in absurdist cinema, things can and do happen in a ‘reasonless’ fashion; if, however, the auteur is committed to the view that actions have consequences – not as billiard-balls but as some kind of existential reckoning – then those plot-point choices need to reveal how this fundamental fabric is being woven.

And indeed Gilligan does take this view: as he put it, “If there’s a larger lesson to Breaking Bad, it’s that actions have consequences… I like to believe… that karma kicks in at some point, even if it takes years or decades to happen.”

Gilligan’s appeal to ‘karma’ is of interest, because that notion (the Sanskrit word simply means ‘action’) is an ontological claim. The ‘karmic world’ is, and indeed operates, by means of causal laws: every action has a consequence, and each consequence is bound up with a dynamic nexus of other conditions and subsequent causes. This account of the absolute connection between cause, its conditions, and effect also necessarily denies the discrete or independent reality of the ‘objects’ and ‘persons’ within the causal structure: every thing – a rock, a cat, an airplane, a human being – is what it is because of the conditions that have created it. Each material state of affairs is constantly changing (in much the way that Walter White pictures our chemical reality). Hence the notion of ‘dependent arising’: all things depend upon, and are the product of, a previous set of conditions; all things are aggregates only temporarily assembled, and constantly shifting in their construction. (Alteration can, of course, be brutally swift, and the Breaking Bad series has some breathtakingly gruesome illustrations of this principle: Victor, at one moment Gus Fring’s assistant and henchman, the next a garroted corpse, the next – dissolved matter in a barrel of hydrofluoric acid; Gus, in his turn, adjusts his tie after Hector’s suicide bomb, not yet aware that half of his face is now missing.) No thing, no person, has a stable identity, and the aggregate reality is always on the move.

In adopting the concept of ‘karma’, Gilligan is asserting that his storyline reflects the way that things actually are. This point is important: storytellers reliably pander to our craving for comeuppance, and few moments on film are more visually satisfying than the villain caught, or destroyed, especially when that destruction is in part of their own making. Sure, it feels good to see the bad guy get what’s coming: but just who is that ‘bad guy,’ and are we entirely sure about what’s coming? The thrills of justice, or vengeance, do not bespeak the deep truth of the karmic picture, and Gilligan seems to be pressing for a depiction with a greater kind of ontological heft. This goal is particularly realized in the events of Season Two.

The second season’s thirteen installments have a comprehensive sense, and that coherence is available in four of the episode titles: episodes 1 (“737”), 4 (“Down”), 10 (“Over”), and 13 (“ABQ”) form a chilling sentence, one that can’t be uttered or understood until the final, horrific scene of a mid-air plane collision. These four episodes all begin in a black and white fore-illumining of what is to come, each one adding more detail to this pending disaster: in the first, a plastic eye is floating in the White family swimming pool; the next three openers amplify our sense of what is to come: men in hazmat suits, evidence bags, a pair of glasses that look like Walt’s. The only color in these four opening sequences is a pink and white one-eyed toy bear, tongue out. In the third of these initial sequences, two body bags are carried to the front of the White’s house; finally, in the last episode (“ABQ”) we see the detached eye, the pink and white mutilated bear, a burnt book, a shoe, once again the two body bags: and then the camera pans out as the scene regains a livid color, two plumes of smoke staining the horizon.

How Did We Get Here?

Consider a central storyline of Season Two: if Season One focuses on Walt’s family, and the meth-cooking crew that he attempts to assemble, Season Two has much to say about the neighbor. And who is a ‘neighbor’? A ‘family’ is constituted by bonds of consanguinity (ones that, as both Aristotle and Hume remind us, are profoundly deep), and the shared task of survival through shelter, food, socialization; a ‘crew’ or ‘team’ is assembled and disassembled as the goal of the shared project shifts (is Mike, or Lydia, foe or friend? That depends). The ‘neighbor’, however, seems conceptually distinct from both of these. A ‘neighbor’ suggests a person in regular proximity: next door, down the street. Neighbors are, at the very least, potentially involved in maintaining a common environment; watering plants, taking in the mail, watching out for children playing in the street or suspicious characters loitering. One funny moment in the series’ final season (episode 9) is the Whites’ next-door neighbor’s reaction to seeing Walt in front of his former house, now fenced off and boarded up; Walt, who has become nationally infamous as the drug lord ‘Heisenberg,’ greets her with a smile and the usual friendly greeting: “Hello, Carol.” (Carol, terrified, drops the sack she’s holding.)

We may, and often do, feel a special kind of civic responsibility for the people we live amongst. If I see a neighbor struggling with their groceries, I may help out (open a door, carry the bag); the neighbor is a fellow dweller, and some sense of maintaining an orderly, even friendly, environment, is important. Again, proximity matters: I probably won’t attempt to help a stranger in another community with those groceries – my efforts might be misunderstood.

In Season Two, the crucial story of neighbors, and their mutual care (or the disastrous abuse of it) is, of course, Jesse’s arrival at Jane’s duplex. Both are wounded creatures – Jane is in recovery from drug use, and Jesse is now estranged from his family. Jane is initially dubious about Jesse; Jesse tells her that he “didn’t meet his parents’ expectations again” and that he just “needs a chance;” she relents and rents him the adjoining, identical apartment. These neighbors become friends, and then lovers. Jane, like Jesse, is an artist, and their conversations provide a respite from Jesse’s world of drug distribution. When Jesse assembles his team to describe their ‘sales protocol’, the meeting is ‘clean’ – soda, pretzels, and the warning that no drugs will enter, or be used, in his house (thus keeping up his neighborly promise to Jane).

In this ‘duplexity,’ one side of the building houses a recovering addict, while its mirror-image, conjoined ‘other’ hides a drug dealer. Which apartment will prevail in defining the neighborhood? Jesse’s sense of himself and his environment begins to shift, but the terrors of selling meth are never far away. One of his ‘distributors,’ his friend Combo, is gunned down in a territory dispute, and Jesse’s horror and rage tip the balance. He tells Jane that he is going to smoke some meth, and that he wants her to leave. She replies, “You could come with me to a meeting –” and reminds him that drugs won’t help. Jesse insists that they will, and the next scene makes it clear that Jane is now using again. The fall from fragile grace is swift: Jane brings home a heroin kit and teaches Jesse how to inject himself.

Walter – who claims that he is trying to get out of the business – finds them both passed out when he breaks in to retrieve the 38 pounds of ‘product’ that Jesse has stashed under the sink. The sale is made (and prevents Walt from being present when his daughter is born); Walt subsequently tells Jesse that he is keeping his half of the money until he stops using. When Jane discovers that Walt has Jesse’s money, she blackmails him into returning it. Now Jesse and Jane can run off to New Zealand… but of course the temptation to have one last heroin binge is too much (indeed, it is what their lives together have become). Walt returns once more, and again finds them in a drugged stupor. He tries to wake up Jesse, but accidentally knocks Jane onto her back. She begins to choke on her own vomit, and Walt makes no effort to save her. She dies as Walt watches.

Before thinking about what kind of responsibility is at work here, and who bears what sort of blame, we should revisit the concept of ‘neighbor,’ this time in an existential mode.

Walt’s brother-in-law Hank, a moral hero

Who Is The ‘Neighbor’?

Our initial sketch had to do with human proximity, and the practical concerns that a shared environment create; in this case, the ‘neighbor’ is perhaps just a more stable version of, say, a ship’s crew. Kierkegaard, in his account of the human condition, finds this characterization of the neighbor radically insufficient; in fact, he argues, “…the neighbor is all people.” Kierkegaard, in his meditation on Matthew 22:39 (“You shall love the neighbor as yourself”) remarks, “The concept ‘neighbor’ is actually the redoubling of your own self…”

The literal ‘duplexity’ of Jesse and Jane is suggested here. Each recognizes a kindred talent, suffering, and compassion, and each wants to help the other: both Jesse and Jane see their own humanity reflected in the other. Now, as Jane puts it, they are ‘partners’ (she rejects the notion that Walt ever cared for Jesse’s actual interests, and asserts that “I’m your partner.”) But this ‘redoubling’ of the self is not, in this case, enough, since this understanding of mutuality is not shared by any of their other ‘neighbors’: Jane’s father, Donald, wants her simply to follow his orders; Walt certainly wants Jesse to follow his. In the darkly serendipitous meeting of Walt and Donald at a neighborhood bar, both complain about their children; Walt identifies Jesse as his ‘nephew.’ Donald, in describing his frustration with Jane, is on the way to the right idea when he remarks: “Family. You can’t give up on them. Never. I mean, what else is there?” Kierkegaard reminds us that there is something else, the neighbor: had Walt seen Jane as a person, like himself, in mortal need, she would not have died. Walt yells “no, no, no” as she begins to choke, but for Walt a detached perspective prevails: Jane is better – for Walt – out of the way; it isn’t, after all, his fault that she injected heroin on this occasion. Nonetheless, he weeps as she dies, perhaps recognizing that this act has finally banished him to a windowless, isolated cell of the self, with no means for seeing the absolute connectedness of all persons and events. Walt is sentenced to an endless round of his own desires and devices (much as he will later be in the ‘safe house’ in New Hampshire: he is safe from the authorities, but not from himself).

This network of connections is, of course, what Kierkegaard’s ‘redoubled’ neighbor recognizes. A person’s joys and catastrophes, puzzles and pains, can only be understood in light of the neighbor’s concerns, because the emerging situation, and the persons within it, is being mutually constructed from moment to moment. If Walt had rescued Jane – what then? The new narratives are unknowable, but one outcome is eliminated: the particular tableau given to us by Vince Gilligan, that day, and that moment, in which Jane’s father Donald is too overcome with grief to do his job as an air-traffic controller.

The notion of ongoing ‘mutual construction’ is a favorite existential theme in the novels of Dostoyevsky. In The Brothers Karamazov, the character Father Zossima provides a sermon about our intersubjective condition, lessons he in turn learned from his brother, Markel. On his deathbed, Markel has an ontological insight: first, as he puts it, “…every one is responsible to all men for all men and for everything.” In acknowledging how every choice we make alters the existential state of play, a person must take responsibility for the way that things now are. Father Zossima puts it this way: “…all is like an ocean, all is flowing and blending; a touch in one place sets up movement at the other end of the earth.”

Walt, after the airline collision, is quick to deny that he – or anyone else – is culpable for what happened. When Walt (Season Three, episode 1) is asked to speak to a gymnasium filled with confused and grieving high school students (one girl asks, “I just keep asking myself, why did this happen? I mean, if there’s a God and all…Why does he allow all those innocent people to die for no reason?”), he tells the stunned assembly that they must “look on the bright side” (it’s only the 50th worst air disaster in aviation history, and a ‘tie’ at that), and reminds them that “People move on.” Jesse asks Walt if he knows that Jane’s father Donald is in fact the air traffic controller responsible for the mid-air crash; Walt answers, “You are not responsible…there are many factors in play there – I blame the government.” Jesse, now better attuned to thinking about who he is and what he’s doing (not necessarily for the best, as it happens), replies, “You either run from things or face them, Mr White.”

Mr White is getting better and better at avoiding his place in these developing disasters, but Jesse has always had some sense of being the ‘existential neighbor.’ Father Zossima exhorts his listeners to be careful at all times, especially around children: “Every day and every hour, every minute, walk round yourself and watch yourself, and see that your image is a seemly one. You pass by a little child, you pass by, spiteful, with ugly words, with wrathful heart, but he has seen you, and your image…may remain in his defenseless heart. You don’t know it, but you may have sown an evil seed in him and it may grow…” Jesse is particularly careful with children: recall the filthy and untended little boy in the care of Spooge and his addled wife. Jesse teaches the boy to play ‘peekaboo’, and makes him a marshmallow fluff sandwich when he says “hungry.” After the Grand Guignol demise of Spooge under a stolen ATM machine, Jesse makes sure that the boy is safe from the scene, wrapped in a blanket, waiting for the police. “You have a good rest of your life, kid,” Jesse tells him. Maybe he will.

But not Walt. In the series’ final moment, as he collapses in a meth lab – faintly smiling? – there is some relief in the camera giving us the longer view, with the police now swarming the compound. We wish to get further away from this face, still absorbed in whatever triumphs or setbacks Walt’s last thoughts circle around. More panning back, perhaps in time, and now we can see the mural Jane painted on her bedroom wall: herself, floating in space, a pink teddy bear flying high above her.

It is good to want to get away from Walt’s face filling the screen, but perhaps we haven’t wanted this respite enough? That sentence, composed of episode titles, can now be read: “737 Down Over Albuquerque.” In Episode One, surely the title ‘737’ was a reference to Walt’s calculation that he only needed $737,000 to get out of the ‘meth-making business’? (The pun here is irresistible.) And those black and white opening sequences, each with a few more details: the White’s own swimming pool; glasses that look like Walt’s; two body bags in the driveway (surely Jesse and Walt!): we viewers are always looking out for the welfare, or fate, of our characters, until our own self-involved anticipation – what will happen to our players? – finally explodes in the sky. Those expectations, teased out of us by the plotting of Season Two, are revealing. Even though the action necessarily focuses on a set of characters, they too belong to a wider world. The actions of Jesse and Walt – and Gus, and Mike, and Jane, and Hank, and Skyler, and Elliot, and Walt Jr., and – everyone – are always in play, on the move, and, in each case, ‘all are responsible for all.’

© Prof. Sheridan Hough 2016

Sheridan Hough is Professor of Philosophy at the College of Charleston.

• A longer version of Sheridan Hough’s essay will be appearing in Philosophy and Breaking Bad (to be published by Palgrave-Macmillan in Nov. 2016).