Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Ayn Rand (1905-1982)

Martin Jenkins traces the life of a self-made woman.

Most philosophies are named after their founders following the founder’s death – for example, Platonism. Sometimes the name emerges from a consensus of its practitioners – for example, Existentialism. It takes a bigger than average ego to consciously create a philosophy and give it a name of one’s own choosing. In For the New Intellectual (1961), Ayn Rand wrote, “The name I have chosen for my philosophy is Objectivism.”

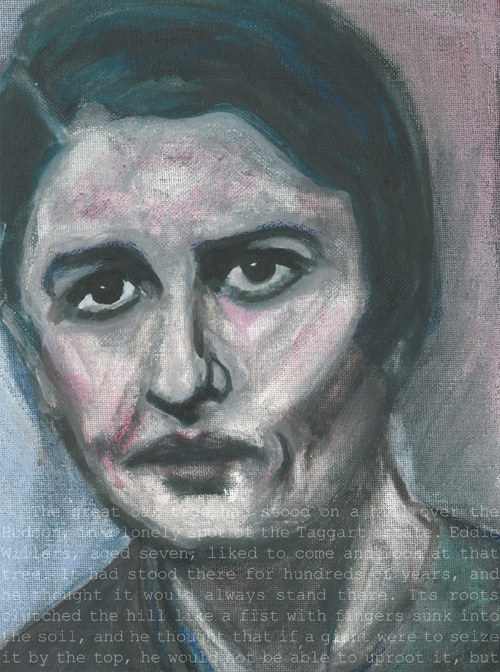

Ayn Rand by Gail Campbell 2019

Russia & America

Ayn Rand was born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum in Saint Petersburg in 1905. Her father was a successful Jewish pharmacist. At the age of twelve the October Revolution totally changed her life. Her father’s business was confiscated and the family fled to the Crimea, where they spent the years of the Russian Civil War (1918-21).

Rand is often accused of mythologising her early life, but one passage rings true, and reveals a lot:

“I lived in a small town that changed hands many times… When it was occupied by the White Army [Tsarist], I almost longed for the return of the Red Army [Communist], and vice versa. There was not much difference between them in practice, but there was in theory. The Red Army stood for totalitarian dictatorship and rule by terror. The White Army stood for nothing; repeat: nothing. In answer to the monstrous evil they were fighting, the Whites found nothing better to proclaim than the dustiest, smelliest bromides of the time: we must fight, they said, for Holy Mother Russia, for faith and tradition.”

(‘The Lessons of Vietnam’, 1975)

After the war the family returned to Saint Petersburg, which had by then become known as Petrograd, and Alisa enrolled in the State University. She was awarded a diploma in History in 1924, allegedly after being expelled as bourgeois but then rescued through the intervention of foreign scholars. After this she studied Screen Arts in what was by then Leningrad. About this time she adopted the ‘writing name’ Ayn Rand , although she apparently never explained her reasons for doing so. In 1925 she was granted a visa to visit relatives in Chicago, and she arrived in New York in February 1926, allegedly speaking no English. (If so, she became fluent very quickly.) She attempted to secure visas to bring her family to the USA, but without success.

Writer & Philosopher

Rand moved to Hollywood and got work as an extra, through, it is claimed, a chance meeting with Cecil B. DeMille. Later she worked as a screenwriter. In 1929 she married the actor Frank O’Connor, and became an American citizen in 1931. She embarked on a career as a novelist and playwright, initially with limited success. Then one of her plays was produced on Broadway, and in 1936 she published her semi-autobiographical novel We the Living.

1943 saw the publication of The Fountainhead, her first bestseller. It was filmed in 1949 using Rand’s own script (slightly modified), and starred Gary Cooper. According to some accounts, Rand did not like the film, despite having written it. Other accounts have her thanking the producer and director for staying true to her vision.

Her next novel, Atlas Shrugged (1957) was an expression of the philosophy she’d been developing. It was also her last work of fiction. By the time it appeared, Rand had moved from Los Angeles to New York and surrounded herself with a group of admirers who met in her apartment to discuss her ideas. They humorously described themselves as ‘the collective’. In 1961 she published For the New Intellectual, the manifesto of Objectivism, and for the next twenty years she devoted herself to expressing her beliefs through non-fiction, mainly in The Objectivist Newsletter and through public talks.

Rand tells the story that she was asked if she “could present the essence of [her] philosophy while standing on one foot.” Her reply was:

1. Metaphysics: Objective Reality

2. Epistemology: Reason

3. Ethics: Self-interest

4. Politics: Capitalism

She also wrote that “The motive and purpose of my writing is the projection of an ideal man.” Of course, her ideas are much more complex than this. But it is probably in her fiction rather than in her essays that her intentions become most clear.

The Fountainhead revolves around a housing development project designed by the hero, architect Howard Roark. A key plot development occurs when a member of the development team manipulates a change to the design in order to provide herself with a long term job. This is a self-interested act, which is seemingly in line with the third tenet of Rand’s philosophy so you might expect her to approve; but Rand implicitly condemns it. Roark is presented as having artistic integrity: he does what he believes in, even when it seems contrary to his immediate self-interest. Therefore Roark is true to himself. Here Rand contrasts petty selfishness with the ‘heroic egoism’ that she really believes in.

Rand did admit to having been influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), but also claimed to have rejected his ideas. Her heroes, however, show all the traits of a Nietzschean Übermensch. In particular, her capitalists are consistently tycoons, usually self-made, who own their own businesses and are not constrained by the ‘herd instinct’ of shareholders. (Another Nietzschean trait in Rand is the frequent quoting of her own works.)

The Individual & the State

Rand argued that for most of history, human societies had been governed either by men of violence or by men of mysticism (‘Attila and the witch-doctor’, as she eloquently borrowed from Nathaniel Branden). Neither the violent nor the mystics produced anything: rather, they both took from the producers, whether by force or by what Rand regarded as the fraud of religion. Only in modern times have the ‘producers’ (by which she means capitalists) come to dominate society, under the guidance of reason. But, she argues in For the New Intellectual, contemporary thought is tending to reverse this development.

Her two bugbears were altruism and statism. She never denied that human beings could give unselfishly to each other, for whatever reasons, but she argued against all moral systems which claimed or implied that human beings were obliged to live for others, whether for other individuals or for the community. Her vision of ideal human interaction was instead based on capitalism. Human beings should relate to each other as ‘traders’, each pursuing their rational self-interest, and so engaging with each other in a decent and reasonable fashion, with mutual respect and acknowledging the value of every human being – in E.F. Schumacher’s phrase, practicing ‘economics as if people mattered’. (Interestingly, the novelist and Christian apologist C.S. Lewis gave a criticism of what he called ‘unselfishness’ which closely resembles Rand’s critique of altruism.)

Rand accepted the need for some sort of state. She wrote against all forms of anarchism, including capitalist anarchism, and argued that a state was necessary in order to provide a framework of law and to protect its citizens against aggression, either from outside or from each other. However, beyond that she believed that the capitalist market/trader interaction was sufficient for a good society. But, she noted, the state has a tendency to extend its activities beyond the limited role she advocated. In particular, the state could be taken over by ‘altruism’. This meant that it became a means of redistributing the property of its citizens on the basis of service to each other. That is, it collected taxes on the basis of ability to pay, but supplied services on the basis of need, as defined by the state.

To return to the quotation about the Russian Civil War: in her adolescence Ayn Rand was offered two visions of how the world should be – monarchical or Communist – and rejected them both. She then moved to the United States with a vision of how the USA should be, and slowly discovered that the USA did not live up to her ideal, either. She then spent decades trying to convince the USA to become what she thought it should be.

Criticism & Appreciation

“Sex is the most profoundly selfish of all acts,” says a character in Atlas Shrugged: “A man’s sexual choice is the result and the sum of his fundamental convictions.” In 1954 Rand began an affair with Nathaniel Branden, one of her followers, who was also married. His wife and her husband apparently consented to the affair. In 1958 Branden began the Nathaniel Branden Lectures to promote Rand’s ideas, later incorporating them as the Nathaniel Branden Institute. In 1964, after the affair with Rand was over, Branden began an affair with a young actress. When Rand learned of it in 1968 she was furious. She accused Branden of dishonesty and ‘irrational behaviour in his private life’ and cut off relations with both him and his wife. The Nathaniel Branden Institute had to close. No-one really understands what lay behind Rand’s reaction; but it provoked accusations that Objectivism, despite its overt commitment to reason, had cult-like elements.

Actually it is easy to criticise Ayn Rand. For instance, her interpretation of history in her writings is overly simplistic. For one classic error, consider this: “Capitalism was the system originated in the United States.” (‘Introducing Objectivism’, LA Times, June 17th 1962). Adam Smith would be surprised. She was also unable to appreciate non-Western art; indeed, it can be argued that the only art she really understood was fiction in the European tradition. But one then has to say that she appreciated Ian Fleming and Mickey Spillane, and tap dancing. She may have had a narrow vision, but she was not an intellectual snob.

In fact, Rand can only be understood in terms of her paradoxes. She was viewed as a right-winger in the American tradition, but she supported the right to abortion and opposed the Vietnam war. She despised homosexuality but argued against its criminalisation. She was an atheist, but regarded Saint Thomas Aquinas as her greatest influence after Aristotle. She was a strong-minded independent woman but not a feminist. Rather, she believed that women should look up to men. In The Fountainhead she even presented Dominique Francon as accepting her rape by Roark because he dominated her. But she accepted that women could rise almost to the top – she drew the line at a female President of the USA.

Rand’s greatest weakness was perhaps her belief that her conclusions were the product of uncontaminated reason. If she allowed Objectivism to turn into a cult, it was because she believed that her conclusions, having been reached through pure reason, were the only possible conclusions. She often criticised other thinkers for letting emotion influence their ideas, but she never realised the extent to which her emotions and past experience led her to her own conclusions.

Why then should we consider Ayn Rand’s ideas? First, because she is not, ever, a conventional thinker. However misguided her conclusions may seem, she has reached them through her own effort. Moreover, she asks the kind of questions about interhuman relations and our relationship to the state which still need to be asked, and answered. Even if we consider her answers wrong, we need to accept that she asked the right questions and reflect on what our responses should be to the same issues. For instance, at the end of For the New Intellectual, Rand puts forward two important propositions:

a. That emotions are not tools of cognition;

b. That no man has the right to initiate the use of physical force against others.

It is possible to imagine arguments against both of these propositions: possible, but not easy.

Rand was a lifelong heavy smoker and underwent surgery for lung cancer in 1974. She enrolled in Social Security and Medicare, but this was not inconsistent with her philosophy: she argued that if the state had improperly taken money from you in taxes, you were entitled to a return on your unwilling investment. As she aged, and especially after her husband’s death in 1979, she reduced her activity, but continued to work on a (never completed) TV adaptation of Atlas Shrugged. She died of a heart attack on March 6th 1982. She was buried next to her husband in a New York cemetery. Her tombstone reads ‘Ayn Rand O’Connor 1905-1982’.

© Martin Jenkins 2019

Martin Jenkins is a retired community worker and a Quaker. He lives in London and Normandy.