Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Tallis in Wonderland

On Logos

Raymond Tallis looks into the mystery of the sense-making animal.

The greatest mysteries are often those we are most likely to overlook. Supreme among these is the fact that the world is intelligible to us, at least to some degree. Of course, if we could not make moment-to-moment sense of what was going on around us, there could be no us. Inhabiting an entirely unintelligible world in which nothing could be understood, anticipated, or acted upon with reliable consequences, would be incompatible with life.

But there is no ‘of course’ even about this. That human existence requires a more or less intelligible world doesn’t solve the mystery, it simply moves the mystery on. After all, the vast majority of organisms act, or at least react, and flourish, without making sense of the world. That one thing is explained by another thing is not the kind of thing that bacteria (the most successful organisms) entertain; and at a higher level, the laws of nature as we understand them are beyond the cognitive reach of all but H. sapiens. What’s more, many humans thrived before Newton announced his discoveries or Einstein formulated the General Theory of Relativity.

Let us unpack our sense-making a little. We live in a world in which happenings seem to be explained by other happenings: ‘this happened because of that’. We not only observe causes, but actively seek them out. We also note patterns, connect and quantify those patterns, and so arrive at the natural laws which have proved so empowering, enabling us to predict events and manipulate things. All of this takes place in a shared, boundless public cognitive space, draws on a vast collective past, and reaches into an ever-lengthening and ever-widening future.

The extraordinary character of the sense-making animal may be highlighted by contrasting a wild animal looking for the origin of a threatening signal with a team of scientists listening into space to test a hypothesis about the Big Bang, having secured a large grant to do so.

This suggests another way of coming upon the miracle of our sense-making capacity. Consider the relative volumes of our heads (4 litres) and of the universe (4 x 1023 cubic light years). In our less-than-pin-pricks bonces, the universe comes to know itself as ‘the universe’ and some of its most general properties are understood. That this knowledge is incomplete does not diminish the achievement. Indeed, the intuition that our knowledge is bounded by ignorance, that things (causes, laws, mechanisms, distant places) may be concealed from us, that there are hidden truths, realities, modes of being, has been the necessary motor of our shared cognitive advance. Man, as the American philosopher Willard Quine said, is the creature who invented doubt – as well as measurement, provisional generalisation, and modes of active inquiry.

It takes two to tango. The fact that the world is intelligible clearly cannot be just down to us, otherwise our stories about how things hang together would be somewhere between myths and an evolving consensual hallucination. The balance between the contributions of what is out there and what is in us, between the extent to which the mind conforms to the universe and the universe has mind-compatible properties, is an issue that has had a long history, shared between theology and philosophy.

The Word & The World

One word that haunts discussion of our astonishing capacity to make sense of the world is Logos. In Western culture, its most famous occurrence is in the extraordinary opening verse of the gospel according to St John: “In the beginning was the Logos.” This has kept thousands of commentators busy, because Logos, which is often translated ‘word’ or ‘reason’, does a lot of work – encompassing the Word that was God’s command that the universe should come into being as well as the Word that was made flesh in the body of Jesus Christ in fulfilment of a promise of salvation. At a more abstract level, the Logos is offered as an explanation of the intelligibility of the world: John is indicating that God ensured that His creation and His chosen species should be so designed that the latter should make sense of the former. ‘Let there be light!’ was ‘Let there be sense!’ as well as ‘Let there be stuff!’ However, this replaces one mystery with many others. Moreover, it does not seem to accommodate the story of the gradual advance in understanding, by no means complete, that has been the great, hard-won achievement of humanity. It puts it all in the human starter pack.

Logos has a history beyond even the wide realm of a faith that has filled two thousand years with hope, joy, bloodshed, terror, and oppression. This history – brilliantly summarised in James Hastings’ monumental Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics (1906-1928) – is all the more complex because Logos has a multitude of senses, mobilised in different contexts. It has a field of meanings, with nodes here and there. This is hardly surprising, given that it registers such a profound encounter of human consciousness with itself.

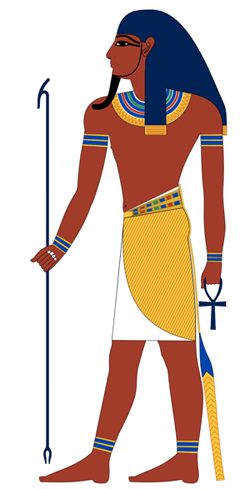

Atum, Egyptian embodiment of reason

© Jeff Dahl 2007

We cannot be sure when something equivalent to Logos first made its appearance in our conversation with ourselves. Some scholars trace it back to the Pyramid Texts of Heliopolis, nearly 2,500 years before St John wrote his gospel. From the primal waters the god Atum arose: he was the light of the rising sun and the embodiment of the conscious Word or Logos, the essence of life.

The Egyptian Logos does not map clearly on to what Logos subsequently became. The term was in common use when the Pre-Socratic philosophers – those “tyrants of the spirit who wanted to reach the core of all being with one leap” as Nietzsche characterised them in Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks – employed it, partly to pat themselves on the back for their own reason-based approach to questions about the nature of the cosmos. Although Logos referred to the way human rationality was reflected or expressed in discourse, it also captured the philosophers’ trust in their own arguments and explanations, and the sense of their awakening from the sleep of Mythos. The boundaries between Mythos – stories told as religious myths or in works of art – and Logos – a reasoned account – will always be contested, and their respective claims to truth likewise. After all, myths, too, are reasoned accounts of a kind: they make sense of making sense, and they use words. What’s more, reason itself operates on a given experience of the world, established long before reason does its work. Hence the endless returns of Mythos.

Logos was central to Heraclitus’s philosophy. According to F.M. Cornford in From Religion to Philosophy (1912), Heraclitus developed – “in flashes of mental lightning” – the notion of Logos as being both the rational structure of the world and the source of that structure. Reason was present in all things. This was asserted against the materialism of the Ionian philosophers, for whom the world was just what was visible. By contrast, Logos was an invisible, immanent reason – the general plan ensuring that the world was an ordered Cosmos rather than a disordered Chaos. It was the hidden harmony behind the discords and antagonisms of existence; behind the eternal war between the elements that kept Being in motion, leaving nothing immune from change. This rational order of things did not itself make the world conscious or thoughtful. Rather, the world became conscious and thoughtful in the human Logos, whose most developed representative was the philosopher himself, in whom the human Logos was united with the Logos of the Cosmos. Making sense of the world was the result of a marriage between microcosmic human Logos and the macrocosmic Logos of the universe itself. Logos provided the link between rational discourse and the world’s rational structure.

The Subsequent Fate Of Logos

We are more familiar with Plato and Aristotle. For Plato, Logos was the rational activity of the world soul created by the demiurge. It could be revealed through Ideas accessed by an intelligence stimulated by the dialectic of philosophical discourse. For Plato, influenced by Parmenides, Logos was revealed in the kind of thought that accessed unchanging self-same Being, real and true, not through sense experience, which is unstable and untrue. According to Aristotle, the Logos was the inherent formula determining the nature, life and activity of the body, as well as, more narrowly, ‘significant utterance’.

These ideas inspired the Stoics, for whom the Logos was a supreme directive principle, the source of all the activity and rationality of an ordered world that was both intelligible and intelligent. It was the ‘seminal reason’ or underlying principle of the world, manifest in all the phenomena of nature. It acted as a kind of force, conferring inner unity on bodies and on the world as a whole, and at the same time guaranteed the intelligibility of the world to humans, since the human soul participated in the cosmic Logos. It is also because the one Logos is present in many human souls that we are able to communicate with each other: we all partake of ‘common sense’. The Stoics’ message was that humans were truly happy only when they were living in a state of harmony in which the Logos of their own soul resonated with the universal Logos, the harmony of nature.

For Philo of Alexandria, a first century Jewish philosopher steeped in Greek thought, the Logos was the model according to which the universe was created. It encompassed the creative principle, divine wisdom, the image of God, and man, the word of the eternal God. At the same time, it was the archetype of human reason, that through which the supreme God made contact with His creation. Logos is the intermediary between God and the world, the creator and His creation.

Which brings us back to the Christian notion of Jesus Christ as Logos. The Logos was the means by which God let Himself into a privileged part of His own creation – humanity. Philo’s connecting the ‘divine thought’ with ‘the image’ and ‘the first-born son of God’, ‘the archpriest’ and ‘the intercessor’, paved the way for the Christian conception of the incarnate ‘word become flesh’, and so of the Trinity. The Word by which He made the world, His law, and indeed Himself, known to man, was now identified with Christ. In the New Testament, the Logos is the Word, the wisdom of God, the reason in all things, and God Himself.

Secularists may smile at such responses to the extraordinary fact that we make sense of the world. But when we think of the alternatives – such as Kant’s claim in The Critique of Pure Reason that the experienced world makes sense because we fashion that world through our senses and understanding, or an evolutionary epistemology that argues that the fit between mind and world is a Darwinian necessity – the smile may fade and wonder return. The endeavour to understand the sense-making animal has a long way to go.

© Prof. Raymond Tallis 2016

Raymond Tallis’s latest book The Mystery of Being Human: God, Freedom and the NHS was published in September. His website is raymondtallis.com.