Your complimentary articles

You’ve read two of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

The Road

Michael Burke traces the lengths to which we must go to truly love the other person.

Speculating on ethics from the bleak post-apocalyptic 2009 film The Road (based on Cormac McCarthy’s bleak post-apocalyptic novel of the same name) seems like a contradiction-in-terms. After all, The Road recounts the journey of a father and son over an inhospitable Earth smothered in a cloud of dust, where civilization is dead and buried under the ashes. Humanity has become a fast-diminishing refugee species, forced to make brutal decisions in the face of bitter cold, starvation, and roaming cannibals, as the beleaguered survivors eke out what little food remains while avoiding becoming food for others. Why then propose this film as an illustration of the ethical thought of Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995), a philosopher who stresses our unconditional responsibility for the welfare of others? In a world where any underlying decency has long ago been squelched by rumbling stomachs, where churches have long since burnt down and ethical treatises have either succumbed to mildew or been consumed as fuel to keep warm, Levinas’s message seems overwhelmingly out of place. Yet it is precisely when the clamor of all the sensible and rational theories of moral obligation have been silenced that his message of an inescapable moral responsibility resonates the loudest. In other words, Levinas’s ethics is the definitive ethics of emergency, for the destitute, the abandoned, the rootless. His ethics is a sure and steady guide along The Road, especially as Levinas and Cormac McCarthy converge in their attempts to salvage a shred of humanity from the gaping maw of an inhuman world.

My Responsibility To The Other

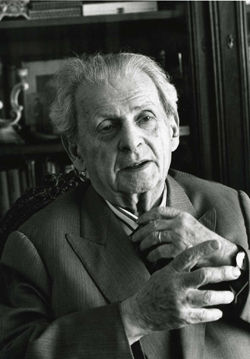

Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995)

What makes Levinas’s ethics so singular is his unrelenting insistence on the individual’s absolute responsibility to others. This is not an ethics where my obligations to the Other (person) are mediated through some general, rational principle, or through some algorithm of utility. I do not calculate how I should act toward the Other by asking what that person would want done in my place, or what an impartial spectator would suggest I do. For Levinas, all these principles and rules for how I should act get in the way of and obtrude my relationship with the Other. Facing the Other, I simply ask: ‘What do you need from me?’ When I encounter another, I ought to put aside my concerns and projects to provide succor to the Other any way I can. There should be no hesitation, no qualification in my response. Levinas says that our responsibility to the Other has no limits. Nor are there any limitations on whom qualifies as the Other. Seeing someone in terms of their gender, race, creed, or any other distinguishing characteristic only risks blocking my access to the singular individual before me. So we bear an ethical responsibility that we have not chosen, to respond to a call of obligation we can never fulfill. If this brief sketch of Levinas’s ethics shows anything, it is the sheer difficulty of living up to your responsibility to the Other. In a sense, it’s impossible –your obligations are never exhausted: the more we meet our obligations, the more that is asked of us. But it is this impossible obligation to the Other that resonates so deeply in The Road.

The Failure Of Theodicy

Before exploring more closely how The Road illustrates Levinas’s ethic, it will be helpful to place his philosophy in context, as a response to the horrors of World War Two, in the wake of which much of Europe was in a condition not a far cry from the devastated ruins of the world of The Road.

As Levinas attested in Difficult Freedom (1990), his life and thought were “dominated by the presentiment and the memory of the Nazi horror.” Yet the genocidal devastation of the Holocaust, which took the lives of several members of Levinas’s family, did not undermine his hope in humanity. Rather, it showed him the moral bankruptcy of ethical systems that magnify rational characteristics or social values over directly addressing the person.

Levinas expounds on the deficit of standard moral theories in light of the Holocaust and other horrific atrocities in an essay entitled ‘Useless Suffering’. Here he addresses the centuries-old question of how an all-loving, all-powerful and all-knowing God could allow humans to suffer. For Levinas, the absurd, superfluous character of suffering is magnified in the light of the senseless convulsions of the Twentieth Century. But despite the various efforts of Western philosophers and theologians over the centuries to justify or explain suffering, often by appealing beyond experience to a supersensible Being, Levinas, not unlike many of his contemporaries, believed a tipping point was reached against these theodicies [theological explanations of evil, Ed] in the Twentieth Century, with its total wars and merciless genocides. It is not merely that the humanistic culture of the Enlightenment, with its emphasis on reason, human rights, and the inviolable freedom of the person, was unable to prevent the rise of murderous totalitarian ideologies, but that these Enlightenment values were fundamentally unable to justify such senseless horror. The point is not simply that no one can write moral treatises, let alone poetry, after the Holocaust. Rather, any attempt to even explain such an event falls flat. So for Levinas, Auschwitz undermines humanity’s ability to make sense of the world, let alone form a plausible theodicy regarding such events.

What separates Levinas’s response here from other accounts, is that rather than trying to prop up the enfeebled moral and social values, Levinas asks what we ought to do in light of this manifest failure of institutional morality and traditional religion. If the devastating events of the Twentieth Century undermine the theoretical framework of the political and social order, perhaps a more appropriate starting point is the interpersonal encounter between the I and the Other, and an unconditional responsibility to the person. Further, if a rational set of moral principles tailored to the reality of human condition has failed to guide human interaction, perhaps an unrealistic moral approach, demanding the impossible, can succeed in its place. In the face of useless suffering, perhaps the senseless kindness advocated by Levinas – of placing the Other’s needs, even their survival, before your own – is the only ‘sensible’ response.

Post-Apocalyptical Ethics

The hopelessness and nihilism that post-war Europeans encountered are paralleled, or rather accentuated, in the post-apocalyptic wasteland of The Road. Indeed, what The Road so forcefully characterizes is the sheer devastation that has befallen the world. Further, there is no explanation of the cataclysmic event: we aren’t told whether it is due to some asteroid, nuclear conflagration, or even the visitation of a divine judgment upon a forsaken humanity. Theodicies can offer neither explanation nor succor in this monochromatic and wasted world. Rarely has the alternative between ethics and sheer survival been drawn so starkly as here. But this contrast also starkly exposes what Levinas ceaselessly promulgates: the blunt opposition between the way of the world and the ethical call. The obliteration of the environment through and even against which humans have so long defined themselves, opens up the possibility of encountering human beings beyond any doctrine – simply face to face. Neither nature nor culture any longer mediates one’s encounter with the Other. The people encountered in the story are for the most part stripped of the identifying categories that Levinas castigates as submerging the uniqueness of the individual brought out by the ethical encounter, such as ethnicity, political affiliation, or religious creed. What predominates instead is need, vulnerability, and hostility.

The cries for help often go unanswered by the father, the protagonist of the film (Viggo Mortensen) who is bent on continuing on The Road and keeping his son (Kodi Smit-McPhee) alive. Bereft of other sanctuary, father and son find refuge in one another. This relationship between the father and the son epitomizes the unconditional devotion of the ethical bond, both in the father’s unstinting commitment toward his son, and in the son’s equally unsurpassable dedication toward his father.

Although the father’s unrelenting drive to do whatever it takes to save his son marks him as a likely representative of a Levinasian self called to an infinite ethical obligation to the Other, I think that the son provides a better example through which to see Levinas in The Road. Although both the father and the son repeat the mantra that they are ‘carrying the fire’ – a catchphrase which guides their conduct, epitomized most clearly in their stricture against eating other people – the son embodies this ideal more fully than the father. It is unclear as to whether the father actually believes this ‘code’, or whether, as intimated increasingly throughout the journey, it’s simply one of the father’s ‘old stories’, calculated to motivate the son to continue the journey. The son, however, constantly advocates for those they come across, whether for a dying man, a thief, or a rambling old man. In response to the father’s question about responsibility, with its Biblical resonances of being the keeper of one’s brother, the son replies that he worries about everything and everyone – an apt summary of Levinas’s injunction to care for others unconditionally. Perhaps the son, by his actions, or by his very presence, prevents the father from degenerating to the desperate measures that others around them have adopted.

Father & Son help an old man on the road

The Road images © Weinstein Co./Dimension Films 2009

Unsaying The Apocalypse

What unites McCarthy and Levinas is their common effort to express the inexpressible. Levinas is well aware of the tension upon his call to our ethical obligation to the Other caused by depicting the Other, since to comprehend the Other, let alone measure our ethical responsibility to them, limits and distorts the way our ethical responsibility reaches us. Levinas is hard pressed to avoid his suspicions that he has already betrayed the inviolable nature of the self’s responsibility to the Other even in merely discussing them.

Unlike other post-apocalyptic stories, The Road deprives the viewer of reassurances of something better to come. There are no precious books to reignite the fires of civilization; no triumphant return of nature; no sense of freedom or vindication with regard to the overturn of the old, corrupt status quo. The desolation and despoilation of the world is near complete.

Time has also contracted for the wanderers, flattening into a monotony bereft of conventional chronological references or temporal markers. The opening line of the book captures this erasure of distinction well: “Nights dark beyond darkness and the days more gray each one than what had gone before.” Coupled with this loss of orientation is the contraction of the world to the things necessary for day-to-day survival. Whatever does not draw the father’s scrupulous attention regarding their survival is ignored. This tunnel vision also underscores his truncated sense of time – of a past impossibly distant and excruciatingly painful when viewed from the present, and a future doled out in the next scrap to be found, the next meager shelter to be sought. Memories of a deceased wife and a departed world are irrevocably cleaved from a present where they can find no foothold. An interplay of abstract ideas is also absent from the dialogue. Littered with archaic, obscure words, The Road’s focus on dead and dying words illustrates how the apocalypse might also transform thought and language.

Levinas grapples with a similar dynamic of transforming language, for instance through his distinction between ‘saying’ and ‘said’. He argues that the Other’s uniqueness – the way they express or say themselves to your self – cannot be captured through the stale, general concepts and empty terms of rational argumentation – what is said. And even though Levinas employs traditional spatial and temporal terms to depict the Other, such as the height from which the Other calls to us, or the distant past from which it summons us, the concepts are drained of their conventional meaning. This height cannot be traversed; this past is so remote as to have never transpired. These puzzling formulations of space and time accentuate that the Other stands apart from context – the Other is not a character within a shared spatial and temporal context. For Levinas, the said (rational discourse) seeks futilely to compensate for the absence of a shared world. However, both Levinas’s and McCarthy’s response to this decentering from time and space is through a storytelling that is a speaking to the Other rather than a speaking about the Other.

At first glance this point seems counterintuitive for The Road. After all, the exhaustion of narrative is in part the point. The allusions to the silent monoliths of a forgotten civilization, to the mute agonies and imponderable rhythms of nature, attest to the end of the human story, the impotence of human theory, and in particular, to theodicy. In the face of such devastation, words have been divested of their power. The son has even tired of his father’s tales of the past, of deeds of goodness and heroism, complaining that these stories are not true, yet offering no tales in their place. Yet the reaching-out of story-creating and story-telling remains. When the father dies, the boy kneels besides him, saying his name over and over again. Although this is a name we never hear or even need to hear, it assures us that through his love this man fashioned an identity, the story of a self, and that in the desolation of the world’s ending, the father’s life meant something. The boy also promises to talk to the father every day – a promise of love that validates the use of memory which the father had once thought too harmful in this world, since all it seemed to do was evoke the pain of loss. So the conclusion of The Road intimates that the boy will assume the father’s mantle in continuing to tell stories, talking to his absent father every day not in order to chart the passing of time or understand the world, as much as to sustain his relationship to the father, and by doing so, sustain goodness and love in the world. This practice strikes close to the concept of saying Levinas uses, insofar as saying consists not in explaining or pigeonholing the Other but in being exposed to however the Other comes across to you, and thereby keeping an open relationship to them.

Terminus

The world of The Road cannot be put back together or made right. This runs contrary to the assumptions guiding most theodicies. But this bleak comment on the future is an affirmation that the world must be faced and lived in as it is. It deploys themes all too familiar to the reader of Levinas’s philosophy: the frailty of goodness and redemption, and the isolation of the individual in and from the vast, senseless universe surrounding her. Such fragile goodness is exhibited The Road in small acts of senseless kindness, whether it be the father and boy sharing their meager supplies with a bedraggled stranger, or the family at the end adopting the now orphaned boy. Yet one must not be misled by this last fleeting glimpse of goodness. Such acts will not save the world. Things cannot be made right.

Levinas also acknowledges that there are no guarantees or unequivocal measures to be taken to ward off evil. Nor is there any certainty that history will not repeat itself in new and more horrendous holocausts, be they human, animal, or planetary. Perhaps it’s enough to be content with acknowledging the fragility of our civilization, with its Bibles, Mona Lisas, and Constitutions, and, as McCarthy in a rare interview with Oprah Winfrey pithily summed up, “Be grateful.”

© Dr Michael J. Burke 2016

Michael is Associate Professor of Philosophy at St. Joseph’s College, NY.