Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

On Bowie by Simon Critchley

Daryn Green looks, listens, and thinks about the art and philosophy of David Bowie.

When I started my Philosophy degree in 1983, if someone asked me what music I liked, my proselytizing reply was “Bowie, Bowie, and Bowie!” Over the years little has changed. From this the reader may discern that I have a certain amount in common with the philosopher and Bowie fan Simon Critchley, author of On Bowie, a short, personal and penetrating book on this pre-eminent artist and song-writing phenomenon. David Bowie – born David Jones – sadly died a year ago, aged 69, still at the very top of his game. In twenty-five concise essays Critchley takes us on a journey from his own reaction to first seeing Bowie on TV in 1972 to his reaction to Bowie’s death. During this journey he’s essentially asking, what is it about this artist, his personas, and his work, that manages to have such a hold over so many? Of course, quite early on there was the gender-bending, the outlandish appearance, the youth-antheming; but there must be more to it than that. And Critchley, as a philosopher, is well placed to probe this further.

Philosophy & Art

Bowie evidently had some sort of relationship with philosophy, which fed strongly into his craft. I’m not saying that Bowie was a philosopher in the conventional sense, only that he had a certain depth and breadth, and a visceral reaction to the broader philosophical landscape. This included aspects of aesthetics, of course, but also involved exploring contemporary issues of the human condition and the blasted terrain of modern spirituality.

Bowie also maintained a lifelong interest in the visual arts. Clearly he saw himself more as an artist in the theatrical or fine-art mould than as a conventional rock star. In comparison to the visual arts, most popular music tends to be terribly constrained. But for anyone with a foot in both camps it must seem perfectly natural to try and get some of the freedom of the former into the latter; in other words, to turn pop music into a flexible and reflexive art form. With Bowie, as with Andy Warhol, there is the sense that literally anything is potentially useable for the artist, and that any censorship is to be on the artist’s own terms. But the question remains: how did Bowie, more than any other rock star (in both my and Critchley’s view), and with commercial success, manage to so consistently transcend the mundane?

Critchley talks about Bowie’s repeated use of Warhol’s aesthetic – the sense of an ironic self-awareness for both artist and audience, born of repeated inauthenticity, that is facilitated using obvious fictions and characters, the use of fictions within fictions, and the exposure of artifice. Bowie’s lyrics often display his sense of being inside his own movie, or reveal himself as the writer. Critchley also covers Bowie’s conversion, via William Burroughs, to Brion Gysin’s cut-up technique – literally the cutting up and rearranging of passages of text to create lyrics or musical ideas. Bowie was terrifically successful with this technique.

But Bowie’s ability to excel didn’t just stem from applying art theories and techniques. One of Bowie’s many tools Critchley identifies is his use of notions of personal identity. Most people, and most song lyrics, assume that identity has a natural narrative unity. Bowie played with ideas that are more sophisticated and liberating and, claims Critchley, more in line with his own view of identity being “at best a sequence of episodic blips.” This is said in connection with David Hume’s idea of the self as being a disconnected bundle of perceptions, and with a belief, such as Simone Weil’s, in “ decreative writing that moves through spirals of ever-ascending negations before reaching … nothing.”

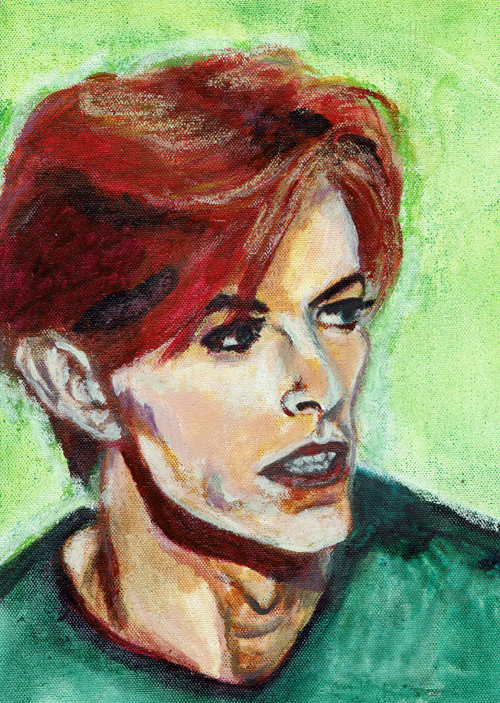

David Bowie portrait by Gail Campbell 2017

Disconnection & Exploration

Once these major influences, tools, and objectives are looked at together, one starts to see some obvious marriages between them, especially (as Critchley notes) that the Gysin cut-up technique and Warholian irony blend perfectly with Bowie’s oblique strategies in tackling notions of fragmented identity and fragmented lives. Bowie famously had a tendency to quickly change styles through a process of “inhabitation, imitation, perfection and destruction” (Critchley likens this to Gustav Metzger’s idea of auto-destructive art). Critchley explores how all these strategies relate to the media-dominated speed, unreality, contingency, even absurdity, of life today and to the transience of experience.

Critchley also writes at length about Bowie’s strong interest in religious ideas. Whilst Bowie had very strong spiritual leanings, he was deeply critical of organised religion, perhaps of Christianity most of all. It is perhaps not surprising that he had a lifelong interest in Buddhism. Critchley notes how often the word ‘nothing’ appears in Bowie’s lyrics;. This tends not to involve the usual meaning (complete negation) but to lean more towards a “restless nothing shaped by… our fearful sickness unto death” or something like the Buddhist notion of a selfless meditative state on the path to enlightenment, which within Bowie became “mobile and massively creative.”

The brevity of this book belies its scope. Critchley covers various of Bowie’s themes: mortality, transformation, transcendence, humour, utopias, dystopias, madness, alienation, Nietzschean sensibility, imaginary pasts and futures, Hamletesque characters and reflections, fear of isolation, yearning for love or connection. He talks of how Bowie permits a “deworlding of the world” where we acknowledge disconnections in order to see things afresh.

The highlight of the book for me was the notion that “authenticity is the curse of music from which we need to cure ourselves.” I think Critchley’s really on to something here, at least as far as popular music is concerned. Although he writes in a non-technical manner, I think he’s driving at ideas of cultural authenticity from existentialism and aesthetics, as relating to notions of street credibility and of authenticity of expression – of an artist being faithful to himself by portraying situations or emotions realistically. There is much good music that does comply with these notions of authenticity. However, by allowing himself a “variety of identities” placed in a “confection of illusion… at the service of a felt… truth” Bowie managed to produce art that responds not just to who and where we are, but also, and especially, to our yearnings for imaginary, sociological, and theatrical exploration. These yearnings are for personal reinvention that can save us from suburban boredom – or even “save us from ourselves, from the banal fact of being in the world.” In any case, for many of us, such yearnings are just as much a part of who we are as the more mundane facts about us. In this sense Bowie’s art could be seen as a rarer, more sophisticated form of authenticity, which shows the simpler form of mundane, factual authenticity to be merely an artistic limitation. To paraphrase Critchley, a true artist requires sufficient elbow room to work their material, so as to produce a more interesting level of authenticity – as Bowie himself repeatedly demonstrated.

I was glad that Critchley also covered Bowie’s extraordinary artistic discipline – his determined way of surviving at the top; and also how his “music is felt in the… musculature of the body” – which hints at Bowie’s tremendous skill with mood, timbre, and rhythm. But I would have taken the analysis of his art a little further. In my view Bowie was not just different; he was also often, and in so many ways, conventionally good; or I might say, conventionally better. His attitude to researching a theme; or his ability to collaborate effectively; or the quality of the acting in his singing; or his ability, lyrically and musically, to form structures at once so sophisticated and yet so accessible – none of these are unconventional attributes as such. It was therefore a killer combination of convention and idiosyncracy that made Bowie the Exocet missile of his profession.

Omnidirectional Bombardment

So how did Bowie manage to so consistently transcend the mundane? Critchley answers this question in a cumulative, integrated and sophisticated way, but the answer is also worth stating more bluntly. In essence, and quite at variance with the notion of laid-back cool so often adopted by artists, and often by Bowie himself, he excelled through a canny combination of raw talent, wild imagination, cross-fertilisation, wise collaboration, ferocious ambition, enthusiasm, dedication, art theory and techniques, open-ended curiosity, restless experimentalism, artistic fearlessness, unsentimental productivity, global art and culture, philosophy and spirituality, esotericism, science fiction, future nostalgia, and more besides. Bowie basically chucked everything but the kitchen sink at his art! Under this omnidirectional bombardment, mundanity was all but buried.

I would recommend this book to all Bowie fans with intellectual leanings who seek a deeper understanding of how Bowie managed to weave his magic, for Critchley here has done much of the spade-work analysis that people like me always meant to do but somehow never quite got round to. It’s short, readable and a worthy take on a great artist who by comparison with other musicians was both fascinatingly different and often the same but better – and thus overall much, much better.

© Daryn Green 2017

Daryn Green is a carer, and also works as a supply teacher in North London.

• On Bowie by Simon Critchley, Serpent’s Tail, 2016, £6.99, 192pp, ISBN: 1781257450