Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Bioethics & Medical Ethics

Are Designer Babies Our Future?

Keith Tidman overhears a prophetic dialogue about the pluses and minuses of genetically engineering children.

Sally: I’ve decided to have a baby! I’m sure that won’t surprise you, Pat. But the real news is, I have no intention of rolling the dice over the health and characteristics of my baby. The old-fashioned way was to choose your mate wisely. Instead, I want to leave nothing to chance. I want to decide my baby’s traits. Genetic engineering is making that possible.

Pat: That sounds ambitious, Sally. Maybe too ambitious. I immediately picture ‘mistakes’ – mistakes that get ‘sidelined’, or are handed a disadvantaged life. But before we get ahead of the game, just how do you anticipate pulling it off?

Sally: The buzzphrase is ‘gene editing’. The tool goes by the name ‘CRISPR’ [pronounced ‘crisper’]. It stands for a mouthful: ‘Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats’. The name is ugly; but what it does is a thing of beauty.

Pat: You’re right, the name doesn’t tell me much – although I can already hear alarm bells! But to be fair and not prejudge, let’s go to the heart of the matter. What does CRISPR do? And how will you use it in planning your family?

Sally: I’m grossly oversimplifying, but CRISPR repairs or replaces genes, which it can do faster and cheaper than earlier tools for manipulating genes. CRISPR was first used to fix gene mutations that cause inherited disorders such as multiple sclerosis. You might have seen the term ‘precision medicine’. CRISPR falls under that.

Pat: Hold on right there! What right do we have to willy-nilly judge whether certain conditions are or are not okay? For example, I’ve seen people with Down’s Syndrome living happy, productive lives. Are you saying there will no longer be a place for them in your future world order?

Sally: Not at all; different parents can always make their own choices for genetic intervention or not, for sure. But to claim that harmful inherited disorders must forever be part of, let’s say, human variation, strikes me as too single-minded. I disagree with you when you say we should leave well enough alone, when we have the tools to head off illnesses and disabilities in newborns.

Pat: What I’m really getting at is that future generations might lose something important, such as being different from one another, as a result of us messing with our genes when we’re all chasing the same qualities. Variety is good.

Sally: I seriously doubt we’ll all become cookie-cutter copies of each other! All I’m saying is that I want to increase the odds of my baby having the traits I, not anybody else, would prefer my baby to have – especially given that the traits I choose for my kids might even get passed on to my grandchildren and great grandchildren, and so on. I believe I should have that right as a soon-to-be parent.

Pat: Frankly, I find the prospects scary. It’s pushing the edge of what science should be allowed to meddle with. To my mind, this is all the more reason to take our time to get the technology right. But let’s take the conversation one step further. I’m curious. Which of your baby’s traits would you like to pick?

Sally: You name it: intelligence, athletic ability, immunity to disease, hair and eye color, creativity, height, physical type, gender, memory, personality, longer life… The options are growing as the technology matures.

Pat: Well, that might be great if you can afford the treatment.

Sally: It’s no different than what parents do already. Mums and dads give their kids an edge by forking over money for training, in music lessons, or gymnastics classes, or math tutoring. Just so the kids can be accomplished and competitive, right?

Pat: Yeah, except training doesn’t come with the risks, I imagine, of CRISPR. I agree that the technology sounds intriguing, maybe even transformative. It also makes me shudder – a lot. I fear people getting swept up in hyped promises and forgetting how seriously messed up things might get.

Sally: Sure, I understand. But gene therapy for humans to improve on Mother Nature has been going on for decades. Not everyone is aware of that, and it often gets left out of the discussion, as if gene editing is an entirely new frontier. The main difference today is the big leap in capabilities, and in affordability, that CRISPR offers.

Pat: Well what makes me most uncomfortable is – how shall I put it? – the vanity of parents getting in the way of their making wise decisions. Foolishly competing to have kids who are genetically better than their neighbors’ kids. Ultimately, the question is, what gives you, or society generally, the right to tinker with nature? To my mind, it cuts a bit too close to playing God.

Sally: Humans have ‘tinkered’ for millennia – like domesticating animals and plants through selective breeding. That’s choosing the genetic heritage of animals too. Changing the gene-lines of animals and crops has simply become easier, cheaper, and more commonplace, as the technology evolved. Now, the same possibility of choice is increasingly entering the realm of reality for human beings.

Pat: I’m still wary of the prospect for overreach. Let’s not gloss over the fact that things have gone seriously wrong with medicine, even in the recent past. The horrors of thalidomide are just one example. It hasn’t all been rosy, despite the assurances by scientists that scientists know best.

Sally: It’s true that scientists get things wrong. But as for ‘playing God’, that phrase is itself an overreach for what we’re talking about. Transplanting human organs was once labeled ‘playing God’. The same goes for other medical interventions, like vaccinating children. What was once unnerving became almost ho-hum. With all these things there are risks, sure; but in the long haul, the benefits to our welfare outweigh them.

Pat: Well, it’s one thing to change wheat, or rice, or corn, to make them hardier against pests, disease, and unfriendly weather. Or to make farm animals more productive in their meat or milk. These are all good things, putting food in the mouths of more and more people around the world, especially in regions where the poverty is stark. But it’s another thing to design human babies . I see red flags.

Sally: I was wondering when you’d get around to mentioning ‘designer babies’. The term’s unhelpful. It makes the procedure sound threatening – as well as implying that people like me approach altering their kids’ genes cavalierly and selfishly.

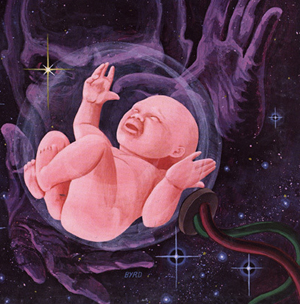

Cover art for Brave New World

Pat: Well, it is dangerously early, I feel, to start choosing a child’s traits – to try to design a baby to your specifications, like it’s some kind of science project. I’m not convinced that the science is ready. I don’t see how you can avoid the nasty unintended consequences – precisely the kinds of mistakes I mentioned. With genetic manipulation scientists are interfering with how nature planned life, and they’re rushing headlong into what it took nature millions of years to perfect.

Sally: But think of CRISPR’s upsides, its potential to improve people’s well-being. You’ve told me before that you believe in God – but if God is good, I doubt he, or she, would mean for us not to improve the cards Mother Nature’s dealt us. In fact, the opposite must be true. And much of science, and all the rest of the stuff that informed society engages in, is intended to do precisely that: make for a better quality of life for us. And as history shows, people have always been curious, exploring beyond the boundaries of current knowledge. That’s not about to stop.

Pat: You downplay the pitfalls. In fact, you’re describing what looks to me like a dark world of unequal classes, depressingly like Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World or the film Gattaca . Manipulating genes may end up deepening society’s division into the haves and have-nots even more than at present. Once more, those with money and influence win life’s lottery.

Sally: Well, all societies have class systems. That’s not going to disappear overnight – if ever. I don’t want to sound like a Pollyanna, but I think that if more parents end up being able to afford these procedures because the technology becomes more widespread and cheaper, it’ll actually level society’s playing field, making society more democratic, not less. That aside, I remain convinced it’s my right – even my obligation – to give my kids advantages. Isn’t that what every mum and dad wants?

Pat: What also leaps uncomfortably but readily to my mind here, is the history of eugenics. The victims on the wrong end of the geneline were treated cruelly, with extermination, forced sterilization, or alternatively, in breeding experiments – all thanks to someone’s arbitrary definition of ‘inferior’ people.

Sally: Eugenics absolutely deserves its sordid reputation! But no one proposes returning to those outrageous abuses. The world has moved on, thank goodness. With CRISPR, and whatever future procedures are developed, parents will voluntarily decide whether or not to pick their babies’ traits. That’s a crucial distinction. It’s all healthy, ethical, and open.

Pat: One other thing. Speaking of ‘open’, will regulations make sure everything’s above board? A wild west of gene editing would be absolutely disastrous. And many people will be needed to help figure all this out, to avoid the loudest voices from bullying others’ opinions or from dictating outcomes.

Sally: Absolutely! Strict controls will be needed, for safety. And the savvy folks in science, medicine, ethics, and politics – as well as the general public, like you and me and our neighbors – will share in having a say in the dos and don’ts – in drawing up the roadmap.

Pat: I’m still not entirely onboard. Lots of concerns are still swirling round my head. But where do you see CRISPR – and especially your own family planning – heading?

Sally: I believe it’s just a matter of time. Eventually people will iron out the scientific, ethical, and social wrinkles, and be selecting their babies’ preferred traits. What’s seen as acceptable will change dramatically over the next twenty or thirty years , and gene editing can’t be uninvented! Personally, I intend to embrace it as far as the means are available. I think not only do I have a right to give birth to a healthy, smart, capable, competitive child if I can, I have an obligation to do so.

© Keith Tidman 2017

Keith Tidman has had a career managing publishing operations. He has written about both philosophy and science, and is also the author of a book on the history of naval operations analysis.