Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Bioethics & Medical Ethics

Henrietta’s Story

Vincent Lotz asks who should have the decisive power over someone’s cells after their death: their family, or the medical community?

HeLa cells are an immortal line of human cervical cancer cells used in medical research. They are called ‘HeLa’ cells from their initial host’s name, Henrietta Lacks. Lacks was an African American woman with little formal education, raised on a tobacco farm in rural Virginia. Born in 1920, she experienced the full impact of racial discrimination left over from the years of slavery in the United States. In 1951, shortly after the birth of her fifth child, Lacks fell seriously ill with cervical cancer. The doctors who treated her took a sample of her cancer cells. After her death, without the knowledge or permission of her family, the hospital’s laboratory used it in a routine experiment they had been performing on every cell sample they received. Henrietta’s cancer cells unexpectedly did not die after a few hours – more the opposite: it was found that if nourished sufficiently they would survive and could be reproduced indefinitely. The remarkably resilient cells became the first human cells to be cultured continuously for experiments. Different strains of HeLa cells, all descended from that original sample, have been invaluable in a wide range of medical research ever since. But is the continued use of HeLa cells just? Who should have the power to give consent for it, and why?

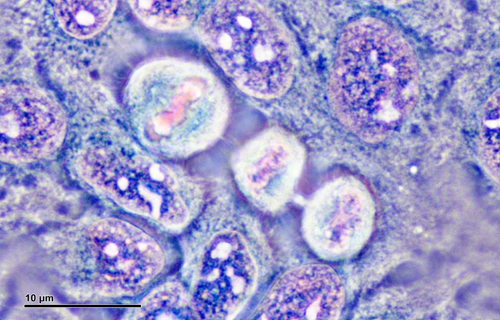

HeLa cells under the microscope

© Dr Josef Reischig

If this question is approached from a utilitarian point of view, one might argue that one offence against one person’s right concerning their body, or parts of it, stands very weakly against the rights to life of perhaps many thousand people who would benefit from their use. From this perspective, it seems sensible to choose the greater benefit for the larger number of people, especially once the person originally owning the cells has passed away. But how do you weigh one right against another? Perhaps our right to our own body parts is absolute. If so, perhaps a policy should be adopted fairly similar to that concerning the treatment of patients in a vegetative state, where the authority to decide future treatment is conferred on the next-of-kin. Thus as soon as the donor of any cell sample passes away, authority concerning the cells’ use should pass immediately to her closest family member; and if none is available, they should fall under the same conditions as hair or other body parts removed after death, whose use is largely prohibited. Logically, the authority should be passed on to siblings or children if there are no parents, since they are genetically the nearest instances. However, it could have been argued that Henrietta’s children lacked the medical knowledge to accurately assess the best thing to do. Is it right to hand over a medical decision to someone who arguably does not adequately comprehend the issues?

When HeLa cells were first cultured, no one really knew the potential they had, not even the researchers. A few years later, when the possibility of their use in medical research became clearer, researchers still made no effort to contact Henrietta’s family. At this point, when there was still comparatively little responsibility linked with HeLa cell use, it would surely have been right to inform her family and explain to them what this discovery meant to medicine and the pharmaceutical industry. This would have allowed enough time for at least one family member to properly understand the issues and make informed decisions. The HeLa cells were still in a legally controllable area, since they were only in the United States and not yet used throughout the world in hundreds of different laboratories; so if the situation had been handled right early on, any such decision would have actually had an impact. A suspicion often voiced is that the handling of the situation then was distorted by race, because at that point in history the US establishment considered black citizens’ rights less obliging than white people’s rights. So years passed, and the Lacks family remained completely unaware that these cells existed. Meanwhile, the cells had become the centre of an extremely lucrative trade, being sold all over the world. When Henrietta’s husband was first informed of the situation, twenty five years had passed since her death. Reports suggest that the initial impact of this discovery was emotional and highly distressing; in some sense, it suddenly seemed, Henrietta lived on in a laboratory, the subject of innumerable mysterious experiments.

Should the law have given control of the cell line to Henrietta’s family? One could give an analogy at this point: If you find a gun rightfully belonging to someone who lives in a peaceful country, has never seen a gun in their entire life, and is unaware that he/she even owned a gun, and if you know there is a person in a war zone who could protect innocent civilians with it, which person should you give the gun to? The answer is intuitively, give it to the one who knows how to use it for good. However, one could argue that this thought experiment is not decisive, since it again leaves out the issues of privacy and your right to your own body, which ethically might be the more important issues.

Personally, I think that family membership can be a reason to shift the responsibility for decisions from the medical community if and only if enough context is provided to enable the family members concerned to fully judge the situation and the choices available. Even then, they may of course choose to pass the decision-making responsibility back to the medical professionals.

After decades of obscurity the name Henrietta Lacks is now widely known, partly thanks to educational efforts by her descendents. A high school was recently named after her, and she has a permanent, though macabre, place in medical textbooks.

© Vincent Lotz 2017

Vincent Lotz is a student at Christ’s Hospital School in Horsham, West Sussex.